![]()

1

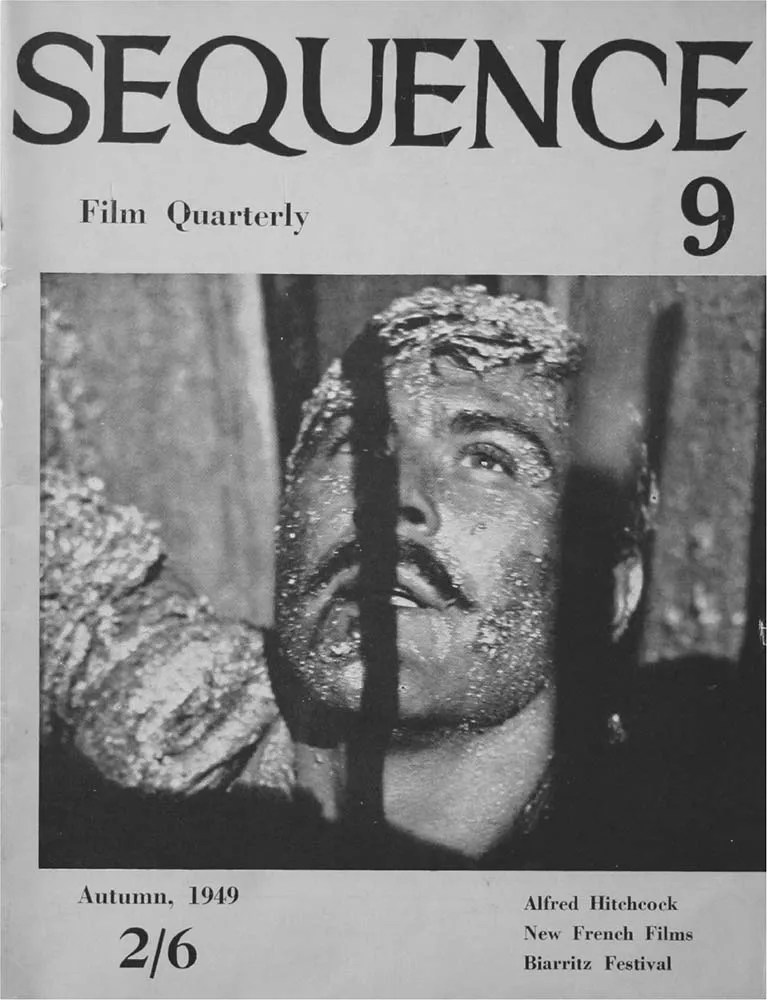

Sequence

The misapprehensions of the received history of film criticism, and there are many, in part result from the tendency of critical and theoretical movements to denigrate their immediate predecessors. Defining one’s own stance may involve – perhaps inevitably involves – the repudiation of established ideas. There is a consequent danger, however, that polemic may become inscribed as history, and therefore a corresponding need to re-examine primary sources.

As later chapters investigate, some of the more radical tendencies of the journal Movie were completely overlooked by Screen when the latter established itself at the expense of the former as ‘the “leading edge” or growth point of film criticism in Britain’.1 Articles and editorials from the time of Sam Rohdie’s accession stress the continuities between Movie and traditional aesthetics – Leavis, English Romanticism, realism – in order to draw attention to the unprecedented departure that Screen represented.2

Another example of an aesthetic buried by a subsequent movement is illustrated by Sequence. The difference in this case is that the interment was effected by critics who had formerly contributed to Sequence themselves. The process by which the Sequence impulse dwindled in the years after its writers became associated with Sight and Sound is a complex one, shaped by cultural forces within and beyond film criticism – and forms the subject of Chapter 2. For the time being, it is enough to say that the Sight and Sound of 1960 under the editorship of Penelope Houston was so far removed from Sequence that the rebellion effected by Movie (and Oxford Opinion) was in many ways analogous to that of Sequence fifteen years previously.

To return to Sequence is to uncover a complex discussion of the director as the artist responsible for a film, a readiness to look for artists in Hollywood cinema, a determination not to be dissuaded from this task in the face of melodrama and a concern with the relationship between style and meaning. These are all attributes that tend not to be associated with British criticism till the advent of Movie. Nor do the points of comparison end here. Both journals were interested in contemporary European cinema as well as Hollywood; both admired Renoir.3 Neither journal had much time for the ‘Film Appreciation’ school of criticism, which presented an orthodoxy common to both periods or, as Charles Barr has noted, the respective renaissances ascribed to the British cinema of each period.4 (That Sequence writers turned filmmakers were involved in the second of these alleged upturns is not without irony.)

Movie’s unique contribution to the study of film centres on its concern with mise-en-scène – not simply as a theoretical concept to support claims for Hollywood directors (which, though extremely important, it shared with Cahiers du Cinéma) but also as the basis of a detailed criticism. Due consideration for mise-en-scène brought film criticism to a maturity which it had hitherto failed to achieve. Yet, preceding both Cahiers and Movie, Sequence attained a sophisticated appreciation of mise-en-scène. In Sequence, however, the discussion went by another name: ‘poetry’. This chapter explores the attributes of ‘poetry’ and its interaction with important related concepts, and recognises Sequence’s place within a tradition of British criticism characterised by its concern with visual style.

Context

For two issues Sequence was the journal of the Oxford University Film Society but was subsequently published independently from London (the move relating to the graduation of some of the participants). Fourteen issues of Sequence were published over a period of five years, the first in December 1946. With the exception of a missing issue for Spring 1950, it appeared as a quarterly from number 2 (Winter 1947) to number 13 (New Year 1951). The fourteenth issue – self-consciously the last – appeared a year later. Substantially reliant on donations for its publication, it records the reluctant decision to cease publication in the face of rising costs.5 The editorial claims that the journal had built a circulation of four thousand, from an initial six hundred.

Figure 1.1 The cover of Sequence, No. 9 (1949)

Sequence was edited, or more frequently co-edited, by six different people. Peter Ericsson, Lindsay Anderson and Gavin Lambert were the major figures. John Boud, Penelope Houston and Karel Reisz were editorially involved in at least one issue. Lambert, a friend of Anderson’s from school rather than a contemporary at Oxford, continued to write important articles after his appointment to the BFI in 1950 as Director of Publications, a job that encompassed the editorship of Sight and Sound. Occasional contributors include Gérard Philipe (No. 7), Lotte Eisner (No. 8), Douglas Slocombe (‘The Work of Gregg Toland’, No. 8), Jean Douchet (an interview with Bresson, No. 13), John Huston (‘Regarding Flaherty’, No. 14) and Satyajit Ray (‘Renoir in Calcutta’, No. 10). Elizabeth Sussex’s book on Anderson claims that the editors wrote material under pseudonyms in order to suggest a greater variety of voices.6

A typical issue consists of: an editorial, ‘Free Comment’; a series of accounts of films in production, ‘On the Floors’; three or four articles; ‘People We Like’, a profile of an actor, often one felt to be unjustly overshadowed; ‘As They Go’, a collection of short reviews of current films; four more substantial film reviews; perhaps two book reviews. The articles cover a range of subjects. The majority are appraisals of the work of a director: there are two on Carné, two on Ford, and one apiece on Preston Sturges, Donskoi, Clair, Sucksdorff, Hitchcock, Walt Disney, Cocteau, Wyler and Milestone. There are also several interviews with directors. There are various articles on movements or national cinemas: Anderson’s ‘British Cinema: The Descending Spiral’, Lambert’s ‘French Cinema: A New Pessimism’, Houston’s ‘Hollywood Warning’. And there are a number of more theoretical articles: ‘Dance in the Cinema’, ‘Creative Elements’, ‘The Director’s Cinema?’.

As the list of featured directors suggests, articles on continental cinema, particularly French, and the American cinema substantially outnumber those which address British films. A number of British films are reviewed, and discussion of the state of the domestic industry appears frequently in editorials and elsewhere, but Sequence is not often to be found championing British work. The editorial of the sixth issue conveys something of the attitude when it defends the journal against the accusation of being pro-Hollywood ‘at the expense of French or British films’, in the following terms:

There is of course no question as to the general superiority of the French Cinema; on the other hand, no need to indulge in odious comparisons to show that the American Cinema is at the moment in a more lively condition than our own. One would have thought that the flow of passionless prestige pictures from Denham and Shepperton, the profusion of hack stuff from the smaller British Studios, would have disposed the London Critics to a more grateful appreciation of the sizeable proportion of gay musicals, witty comedies, well executed dramas which have come to us from Hollywood in the last few months.7

Quotations

In order to support the claim that ‘poetry’ is for Sequence a celebration of mise-en-scène by another name, eight passages have been collected together to represent the range of ways in which the term is employed. These quotations are presented en masse, with commentary on their recurrent and significant features offered subsequently.

A

The work of John Ford is perhaps the greatest vindication of this Hollywood system. Ford has been directing since about 1915, has made an astonishing number of films (more than sixty for certain), some of them poor, some competent, some quite outstanding. The sample one has managed to see shows more clearly that he has been improving, has become in the last few years more assured in technique, more mature in approach; the making of crude Westerns and simple tales of adventure has not unfitted him for filming the sombre, unrelenting Tobacco Road or the humane, dignified Young Mr Lincoln. It has, rather, given him a chance to concentrate on what the camera can do and on learning a technique which seems so effortless as to be no technique at all. Ford is the least mannered of the great directors; people struck by his films are often unable to analyse what they have seen or to remember anything but the final lasting impression: the excitement of Stagecoach, the beauty of The Long Voyage Home, the humanity of The Grapes of Wrath. He never relies on tricks largely because his themes do not lend themselves to self-conscious treatment and partly because he knows he can get the effect he wants without them: in this, as in much else, he is the very opposite of Welles, Wyler or Hecht, whose films have an air of calculated effect, an element of the theatrical. Ford’s films are nearly always clear and straightforward, unfold at a leisurely pace and sometimes attain a visual poetry unique in the American cinema.

Peter Ericsson, ‘John Ford’8

B

[Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath] has a poetry which the book lacked; for instance Ma’s last moments alone in the house she is leaving – the shot of her trying on her earrings for the last time. The film is particularly rich in incidents and characters given with just this masterly economy.

Peter Ericsson, ‘John Ford’9

C

In the work of a director like Marcel Carné or John Ford, one notices that the craftsmanship is inseparable from the material. The greatness of these directors lies not only in their experience of, and expertise in, the medium, but in their feeling for values, character, background, for which the film becomes a medium of expression. Ford’s My Darling Clementine is a supreme example of this. The actual material has been used before in a standard Western called Frontier Marshal, and all the staple recipes for failure are there, but in Ford’s hands the new film takes on a character and genuine poetry of its own. A commonplace story is not merely redecorated, but infused with a beauty and vitality whose source is the imaginative inspiration common to all the best films of Ford. It is still a minor work, but a completely individual one.

Gavin Lambert, ‘British Films 1947: Survey and Prospect’10

D

The backgrounds [of Hôtel du Nord] are as poetic as they are real. The small, bare interiors, the prison sequences with the faces of Aumont and Annabelle seen from either side of the grill [sic], crisscrossed by its shadow, and the little banlieue that springs to life – a canal with a tow-path, high bridge and lock, a cobbled street with tall, shuttered houses. They do not, however, achieve that degree of integration with characters and eve...