![]()

Part I

‘Dharma bums’, 1958–71

![]()

1 Junk aesthetics in a throwaway age

In America, one is either ‘Hip’ or ‘Square’, declared Norman Mailer in 1957. Such are the alternatives: ‘one is a rebel or one conforms, one is a frontiersman in the Wild West of American night life, or else a Square cell, trapped in the totalitarian tissues of American society, doomed willy-nilly to conform if one is to succeed’.1 By 1959, this opposition had been popularised to the point that Life published an illustrated article relishing the contrasts between Squaresville (Hutchinson, Kansas) and Beatsville (Venice, California).2 That same year, Edward Kienholz presented viewers with his image of Mailer’s ‘Square cell’ (figure 10). On a child’s perambulator, on which a mannequin figure of John Doe is mounted, a riddle is displayed: ‘Why is John Doe like a piano?’, followed by the answer: ‘because he is square, upright and grand’. The square John Doe is so ‘upright’, so solid, in Kienholz’s assemblage, that he can be split into two: his torso and head facing forward, and the lower half of his body behind them on the perambulator, legs rigidly stretching upwards. Armless and splattered with paint, waiting to be pushed (or taken advantage of, like a grand piano being ‘played’), the grinning John Doe is anything but ‘grand’. A hanging cross ineffectually tries to fill the void left in his heart, where a pipe connects his torso to his lower body (just above the genital area), visualising the gaping hollowness of his conformism. A possibly menacing grin, mutilations and drips of paint evoking blood and dirt all convey an image of John Doe as both a monster about to run someone over and a victim of the latent violence of a ‘totalitarian society’, as Mailer called it.3

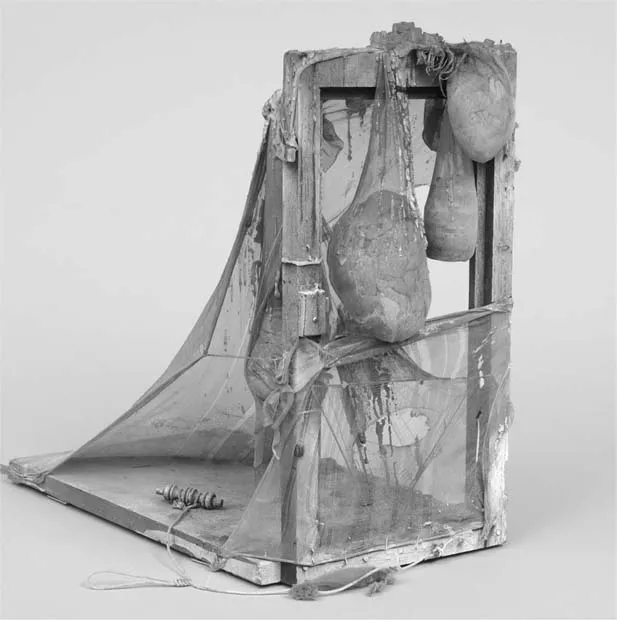

For Mailer, the hipster and beatnik resist such a square society by exploring alternative marginal lifestyles and modes of existence. Does Bruce Conner’s 1960–61 portrait of Beat poet Allen Ginsberg (figure 11) offer a pendant to Kienholz’s square John Doe? An assemblage of wood and stretched nylon sprayed with paint, including assorted detritus and a limply hanging, formless sack, Conner’s PORTRAIT OF ALLEN GINSBERG certainly makes no claims to grandness: it celebrates a voluntary poverty and the original meaning of the slang word ‘beat’ – penniless, exhausted, worn out. Indeed, the work cannot even claim to be a portrait, as it appears to convey nothing of Ginsberg’s subjectivity or identity. The assemblage was partly inspired by Conner’s experience of taking peyote, during which he perceived himself as ‘a very tenuously held together construction – the tendons and muscles and organs loosely hanging around inside’.4 In their explorations of the ‘frontiers’ of American life, the Beats sought such heightened and disorienting perceptions of the self, through mystic experiences as well as drugs.

10 Edward Kienholz, John Doe, 1959

11 Bruce Conner, PORTRAIT OF ALLEN GINSBERG, 1960–61

Though affiliated with the Beat culture that thrived in California during the late 1950s, neither Kienholz nor Conner considered themselves to be ‘Beat’ artists; indeed Conner explicitly sought to distance himself from the label, especially after it had been widely appropriated and distorted by the media. The Beat aesthetic was largely literary, and its intersections with trends in music, cinema and the visual arts took on diverse forms. The visual tendency with which Kienholz’s and Conner’s works were associated at the time was described variously as ‘neo-dada’, ‘assemblage’, or ‘junk’ – junk ‘sculpture’, ‘culture’ or ‘aesthetic’. PORTRAIT OF ALLEN GINSBERG, for example, was included in the second instalment of the exhibition New Forms, New Media at the Martha Jackson Gallery in September–October 1960. The New Forms, New Media exhibitions, and the catalogue in which Lawrence Alloway coined the term ‘junk culture’, paved the way for the landmark Art of Assemblage survey curated by William Seitz at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in which Kienholz’s John Doe would be displayed in October–November 1961. Rooted in the West Coast art scene, the assemblages of Kienholz and Conner were often exhibited at the time alongside the works of New York based artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, John Chamberlain, Richard Stankiewicz and Jean Follett, as well as artists exploring environments and happenings such as Allan Kaprow, Jim Dine, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Whitman and Red Grooms.

Though not central to the reception of such artistic developments, hints of Mailer’s ‘hip’/‘square’ polarity, characteristic of the social landscape of the time, are perceptible in the press reviews of junk art. This perspective was developed more extensively, if awkwardly, in William Seitz’s catalogue essay for The Art Assemblage, as well as in a more focused reflection, published in Artforum in October 1962, entitled ‘Junk Sculpture: What Does it Mean?’ by philosopher Donald Clark Hodges, who referred directly to contemporary reflections on American society, including Mailer’s. Discussing these essays, and wider debates that characterise the critical reception of the 1950s junk aesthetic, will allow me to articulate more specifically some of the relations between junk practices and the society in which they were developed.

In particular, junk in these practices will be shown to be used in varied, and often widely diverging, ways. A simple comparison of Kienholz’s John Doe and Conner’s PORTRAIT OF ALLEN GINSBERG suggests such distinct uses. Firstly, the discarded objects used by Kienholz remain sturdy and recognizable, despite the artist’s interventions (cutting, assembling, painting). In contrast, Conner’s materials are deformed beyond recognition, approximating the condition of dust and decomposition rather than that of the scattered junkyards or thrift stores visited by Kienholz. Secondly, Kienholz mobilises discarded objects in order to mount an angry attack on a hypocritical ‘square’ society, setting up an opposition between the two polarities, whereas Conner appears more concerned with blurring the differences between art and rubbish. By celebrating garbage, Conner inverts the negative value of junk, in much the same way as Beat author Jack Kerouac could exclaim: ‘I love it because it’s ugly.’5 The precariousness of the junk aesthetic, I will argue, lies in such varyingly and variously dynamic relations between art and trash, as they operate through the artists’ choices of materials and their modes of assemblage. The politics of such precarious practices emerge in their interactions with the social critiques concerning the place of the subject in late 1950s and early 1960s capitalism. In particular, I will suggest that the individual’s life and identity at the time were affected by an ever more ‘squarely’ organised society, in which operations of work, consumption and administration were increasingly controlled. It is within this shifting landscape that I will map out various assemblage practices and the debates surrounding them, referring to works by Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg, before focusing more extensively on the exemplary junk practices of Bruce Conner and Allan Kaprow.

Junk

The term ‘assemblage’, explained William Seitz in his introduction to The Art of Assemblage, ‘has been singled out … to denote not only a specific technical procedure and form used in the literary and musical, as well as the plastic, arts, but also a complex of attitudes and ideas’.6 If New York Times critic John Canaday dismissed Seitz’s catalogue as ‘juvenile’ and a ‘bad mix-up of long hair and starry eyes’7 – terms resonating with the ‘square’ criticisms of ‘hip’ subcultures – it was partly because of the different adjectives used by the Art of Assemblage curator to describe the ‘attitudes and ideas’ of contemporary assemblagists.8 ‘Many cultivate attitudes that could be labeled “angry,” “beat,” or “sick”’, proposed Seitz at one point, referring to both the Beats and the affiliated ‘angry young men’ in the United Kingdom.9 Scattered throughout Seitz’s text, the repeated references to feelings of dissatisfaction, impatience, malaise, ‘embittered’ ‘disenchantment’ and anger, all suggest the author’s sympathy with this disaffected generation.10

For his part, Donald Clark Hodges explicitly compared, in his Artforum article, the new ‘junk sculpture’ to ‘the current epidemic of white negroes, hipsters and junkies’, affirming that both ‘are a reaction to growing up absurd in the affluent wasteland’.11 Clark Hodges’s formulation is historically interesting in that it evokes no fewer than four studies from which the author drew in his article – explicitly or implicitly – for his analysis of 1950s American society: Norman Mailer’s 1957 essay on ‘The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster’ (which I quoted above), Paul Goodman’s 1960 Growing up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized Society, John Kenneth Galbraith’s 1958 The Affluent Society, and Vance Packard’s 1960 study The Wastemakers. Goodman had addressed the disaffection of American youth, focusing on delinquents as well as the Beat hipsters celebrated by Mailer; Galbraith and Packard had analysed the problems raised by a new unprecedented growth of industrial production and consumption.

In a similar acknowledgement of the growing literature on socio-economic shifts in 1950s America, Reverend Howard Moody asked, in his 1959 ‘Reflections on the Beat Generation’: ‘Should we be surprised that in the age of “the lonely crowd,” “the organization man,” and “the hidden persuaders” we should get a generation, or at least a segment, that is sickened on the inside and rebellious on the outside at having seen human existence being squeezed into organized molds of conformity?’12 Moody refers here to David Riesman’s bestselling ‘study of the changing American character’ (The Lonely Crowd, 1950), as well as another book by Packard focusing on advertising (The Hidden Persuaders, 1959), and C.S. Whyte’s 1956 study of the Organization Man, on which Goodman drew for his definition of ‘the organized society’ from which the youth felt disaffected. As the minister of the Judson Memorial Church, Moody would invite Allan Kaprow in 1960 to direct a galle...