eBook - ePub

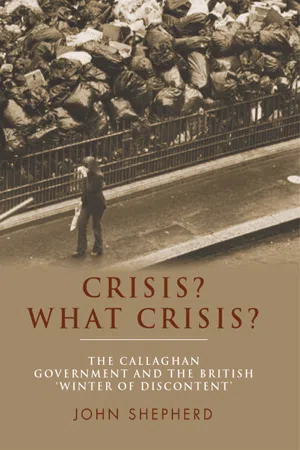

Crisis? What crisis?

The Callaghan government and the British 'winter of discontent'

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The first full length account of the 1979 'winter of discontent'

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crisis? What crisis? by John Shepherd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Television History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The 1970s: ‘winters of discontent’

On 10 January 1979, Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan landed by VC10 at Heathrow airport on his return from an international summit on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, hosted by the French President Giscard d’Estaing, with US President Jimmy Carter and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Unfortunately, to Callaghan’s chagrin, some of the British press reported this high-level meeting on the second round of the US–Soviet Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II) as more of a foreign junket for the world leaders and their wives.

Callaghan returned from the warm shores of Guadeloupe and a short holiday in Barbados to one of the worst winters of post-war years, which seemed in tune with the industrial chaos of strikes, go-slows and work-to-rules in Britain, subsequently dubbed by the press the ‘winter of discontent’.1 Four national rail strikes made travel a nightmare for many people. Even within cities and towns, commuting was hazardous, with ungritted roads during strikes by local authority workers. Even those too young to have lived through those months can often readily cite a familiar compilation of iconic media images and popular memories, such as the mountains of uncollected municipal rubbish in London’s Leicester Square and elsewhere, union pickets at hospitals blocking entry to medical supplies and, probably above all, the refusal of the Merseyside gravediggers to bury the dead in Liverpool – with the rumoured possibility of interment at sea instead.2

The weather during the ‘winter of discontent’ was extremely cold and comparable to the severe climatic conditions experienced in Britain during the infamously harsh winters of 1947–48 and 1962–63. As weather presenters Ian McCaskill and Paul Hudson recalled, snow had fallen during November and early December 1978, followed by heavy rainfall in different parts of Britain. London had ‘its wettest December since records began’. However, the main impact of the treacherous weather – with heavy snowfalls spreading from Scotland followed by more freezing weather – was felt in January and February 1979. At Westminster, MPs devoted parliamentary time to the appalling weather.3 The succession of blizzards sweeping England formed a bleak backdrop to a series of escalating industrial disputes. The combination of unusual, almost arctic weather and industrial disorder in different parts of Britain, reported in graphic detail, particularly by the tabloid press, helped to ensure the ‘winter of discontent’ became etched in the national psyche.4

As the Prime Minister returned from his international summit in 1979, the temperature had dropped to –7ºC at Heathrow and –17ºC at Lintonon-Ouse in Yorkshire. The sun-tanned Callaghan’s tetchy response to a reporter’s question about ‘mounting chaos’ at a somewhat disorganised Heathrow conference with the British media was misreported by the press the next day with the classic banner headline ‘Crisis? What crisis?’5 It seemed to put in a nutshell an out-of-touch Prime Minister and a hapless government battling trade union power as the temperature of industrial relations in Britain soared.6 At the airport, the Prime Minister actually said: ‘I don’t think other people in the world will share the view that there is mounting chaos’. However, Denis Healey later recalled that that infamous headline, ‘Crisis? What crisis?’, would become indelibly associated with James Callaghan in British folklore, much as ‘The pound in your pocket’ became associated with his predecessor, Harold Wilson, at the time of the 1967 devaluation or Healey himself with his own ‘Squeeze the rich until the pips squeak’, in fact a misquote from a speech he made in Lincoln during the February 1974 general election.7

At Heathrow Callaghan was also questioned about whether he should have been abroad at a time of serious industrial strife. The ‘winter of discontent’ had started with a major nine-week strike in the Ford Motor Company in September 1978. This dispute became a catalyst for various forms of industrial strife in the subsequent months. January, February and March 1979 witnessed the height of the industrial disruption in Britain, including the national road haulage strike as the oil tanker drivers’ dispute reached a conclusion. On 22 January 1.5 million public sector employees stopped work as part of a ‘National Day of Action’. In many places, strikes by public service employees continued well after this date, involving local authority manual workers, health service auxiliary staff and civil servants.

In twentieth-century Britain, the ‘winter of discontent’ of 1978–79 witnessed a national outburst of strikes comparable with earlier years of industrial protest, in 1915–22 and 1972–74. In 1979 alone, over 29 million days were lost as a result of around 2,000 stoppages involving nearly 5 million workers. During 1978 there were 2,349 stoppages with 9.3 million working days lost, involving directly a total of 979,000 workers. During January–March 1979 – at the peak of the ‘winter of discontent’ – 5 million working days were lost. The major industrial stoppages involved 20,000 bakery workers (November–December 1978); 57,000 Ford workers (September–November 1978); 7,500 provincial journalists (December 1978–January 1979); 2,200 oil tanker drivers (December 1978 – January 1979); 56,000 road haulage drivers (January 1979); 20,500 railway workers in four one-day strikes (January 1979); 1.5 million public service workers in local authorities and in the health service, in various disputes (January–March 1979); 3,000 water and sewage workers in January 1979; and about 2,500 social workers in social care services (August 1978).8

Crucially, this Shakespearian ‘Winter’s Tale’ seriously undermined Labour’s historic relationship with the trade union movement, out of which the party had been born. Within a matter of weeks, after arctic weather had gripped Britain, the minority Callaghan government lost a vote of confidence, on 28 March 1979, by a single vote (310–311). The May 1979 election returned Margaret Thatcher to Downing Street with a comfortable overall majority of 43 and paved the way for 18 years of unbroken Conservative rule.

Ever since then, the ‘winter of discontent’ of 1978–79, with its dramatic images of industrial conflict – particularly the public sector strikes in early 1979 – has symbolised the Callaghan government’s chronic weakness in the face of all-powerful unions. Enduring popular myths were created and continue to be evoked by Conservative opponents and a hostile media. Yet the 1970s as a whole are often remembered for recurrent crises, poor economic performance and industrial unrest. These years followed a so-called post-war ‘golden age’ of increased prosperity, rising living standards and relative industrial quietism. Then, in dramatically changed circumstances of a world energy crisis, Labour returned to office after the February 1974 general election. Edward Heath’s Conservative government of 1970–74 may be recalled for the imbroglio involving the highly controversial Industrial Relations Act 1971, the Industrial Relations Court and the ‘Pentonville Five’ imprisoned dockers, as well as five declarations of a state of emergency, the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974, and the 1974 ‘three-day week’.9 Faced with this legacy, the Wilson and Callaghan administrations – a minority government for most of its five years – could claim some credit for tackling Britain’s economic and industrial problems. As Steven Fielding has argued, ‘those few weeks that formed the “winter of discontent” were then atypical: despite what Labour’s detractors claimed, rotting rubbish and cancelled burials did not define the [Labour] Party’s period in office’.10

Over 30 years on, the ‘winter of discontent’ still resonates in people’s imagination and can be debated with great passion on all sides. Interestingly, when the Modern Records Centre (MRC) at the University of Warwick officially reopened, after a major refurbishment, on 1 November 2011, the 1978–79 ‘winter of discontent’ was chosen for a special discussion to celebrate the occasion.11 The thirtieth anniversary of the ‘winter of discontent’ was also marked by a public debate before a packed audience at the British Academy in London on 22 February 2009, with a panel discussion and invited contributions from the floor.12

Earlier, in 1987, politicians, trade union leaders, captains of industry and civil servants who had been directly involved at the storm centre of the ‘winter of discontent’ had gathered at a symposium organised by the Institute of Contemporary British History to mull over the key issues in the disintegration of Labour’s social contract and the advent of the winter strife in 1978–79.13

By the summer of 2010, a global financial crisis, following the collapse of the Lehman Brothers Bank in New York on 15 September 2008, evoked comparisons to 1978–79 ‘crisis Britain’. In July 2010, a major three-day conference, ‘Re-assessing the seventies’, at the Centre for Contemporary British History of the Institute of Historical Research, featured a comprehensive programme of cultural, economic, social and political topics setting re-appraisals of the ‘winter of discontent’ in a broader context of late twentieth-century British history.14

In 1985 at Blackpool, in a direct reference to the ‘winter of discontent’, Margaret Thatcher, addressing the annual Conservative Party conference and the nation, asked: ‘Do you remember the Labour Britain of 1979? It was a Britain in which union leaders held their members and our country to ransom … the sick man of Europe.’15 During the 1970s, the unions were often blamed by their opponents for contributing to the downfall of three administrations – the governments of Harold Wilson (1970), Edward Heath (1974) and Jim Callaghan (1979). However, not all agreed with this view of industrial relations in the 1970s. Gerald Kaufman, a minister in the Department of Employment in the Callaghan administration, believed the winter strikes in 1979 had a less damaging effect than the press portrayed, owing to ‘the liaison built up between ministers in several departments and the leaders of the unions concerned’.16

In particular, the ‘winter of discontent’ figured large in the Conservatives’ 1979 election campaign. The myths and realities of the turbulent events continued to feature in subsequent Conservative election victories, in 1983, 1987 and 1992, as the electorate was reminded of the perils in store if Labour won at the polls. In early January 2012, The National Archives at Kew released under the 30-year rule the 1981 papers of the first Thatcher government. Interviewed on BBC News concerning what the newly available official records revealed about the Conservative government’s handling of the 1981 Toxteth riots in Liverpool, Lord Heseltine quickly referred to the ‘winter of discontent’ during the Callaghan Labour government’s period in office.17

The ‘winter of discontent’ represents a decisive turning point in late twentieth-century Britain that led to ‘Thatcherism’, as well as a landmark in the history of the British Labour Party and trade union movement. In 1997 Labour finally returned to office with Tony Blair as Prime Minister, who accepted the 1980s Thatcherite legislation on trade union reform. Under ‘New Labour’, the young party leader resolutely declared, there would be no return to the chaotic chapter of Labour’s past in the 1970s.18

Yet, despite a considerable and expanding literature on the political and social history of late twentieth-century Britain, there is no full-length study of the ‘winter of discontent’ itself. In subsequent recollection, even mythology, the industrial strife of 1978–79 has often been a symbol of Britain’s post-war economic decline and the dominance of over-powerful union barons in British political life.19 There are a number of excellent works on the troubled industrial relations of 1978–79. Kenneth O. Morgan’s magisterial biography of James Callaghan is undoubtedly essential in studying the ‘winter of discontent’, to be supplemented by his study of Michael Foot.20 Edward Pearce has also produced a detailed biography of Denis Healey, which, in a total of 52 chapters, comprehensively covers the history of the British Labour Party, and which provides insights into the Callaghan–Healey alliance during the winter unrest of 1978–79.21

More nuanced perspectives can also be found than the negative...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- 1 The 1970s: ‘winters of discontent’

- 2 Election deferred and the collapse of the social contract

- 3 The Ford strike, 1978

- 4 The oil tanker drivers’ dispute and the road hauliers’ strike

- 5 Public sector strikes

- 6 Media coverage

- 7 The Conservative Party and the ‘winter of discontent’

- 8 Political aftermath

- 9 In conclusion: the ‘winter of discontent’ – views from abroad

- ‘Winter of discontent’, 1978–79: chronology of key events, including by-elections

- Bibliography

- Index