![]()

Part I

From the 1930s to the Cold War

![]()

1

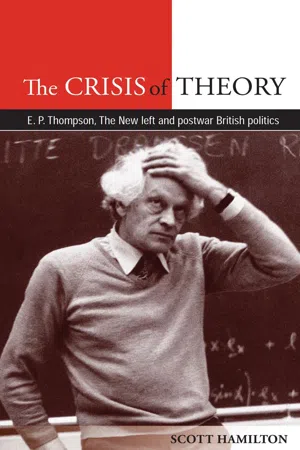

The Making of EP Thompson: family, anti-fascism and the 1930s

EP Thompson is best known as the author of The Making of the English Working Class, one of the great feats of twentieth-century historical scholarship. In The Making and a string of related ‘histories from below’, Thompson explores the lives of ordinary people in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England with such finesse and sympathy that many of his readers assume that he had deep family roots in the world’s first working class. In truth, Thompson grew up in a comfortable suburb of Oxford.

Yet EP Thompson’s roots are not irrelevant to his life and writing. His family and the milieu it moved in gave him sympathies and interests he would retain all his life. It may not be going too far to say that the lives and thoughts of Thompson’s father and brother, in particular, constitute a sort of preface to works like The Making of the English Working Class. There is a continuity, if not a simple identity, between the lives and opinions of the three men.

To Bethnal Green and Bankura

Edward John Thompson was born in 1886, the eldest son of Reverend John Moses, who had served as a Methodist missionary in India for many years before returning to England. A period of financial difficulties followed John Moses’ early death, and Edward John was compelled to sacrifice his ambitions for the sake of his mother and his siblings. Despite winning a university scholarship, he left the Methodist-run Kingswood School to work as a clerk in a bank in the East End of London. After six unhappy years in Bethnal Green, the sensitive young man escaped to the University of London, with the understanding that he would secure a Bachelor of Arts degree before following in his father’s footsteps and entering the Methodist missionary service.1

In 1910 Edward John arrived at the Methodist-run Bankura College in West Bengal. Bankura was a secondary school which would acquire a small tertiary wing, an outlier of the University of Calcutta, in 1920. The years Edward spent in India were a mixture of professional frustration and personal growth. Work at Bankura often seemed no more satisfying than work at the bank in Bethnal Green. With its emphasis on the rote learning of its Anglophilic curricula, the college struck him as little more than a factory. Edward John felt that he was unable to pass on his love of literature and history to many of his students, and he doubted both the wisdom and effectiveness of the attempts of the school authorities to proselytise amongst their largely Hindu charges. In a letter he sent to his mother in 1913, Edward John commented wryly on the difficulties of bringing the word of God to heathens:

[O]ne boy said that at the Transfiguration Jesus had four heads … At the Temptation, ‘Shaytan was sent by God to examine the Jesus … and gave him his power. By the power of Satan he was able to [sic] many wonderful acts.’ Jesus wept over Jerusalem, and said ‘how often I would have gathered thy children together, as a cat gathereth her chickens’.2

Despite or because of his frustrations, the young teacher quickly began a study of Indian society and culture that would last the rest of his life, spawn a dozen books, and make him one of Britain’s most respected authorities on the subcontinent. In 1913, Thompson made a visit to Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali writer and educationalist who had just won the Nobel Prize for literature. Thompson, who was himself a fledgling poet, soon began to translate Tagore’s poems and stories. By 1913 Thompson had become fluent in Bengali; he would eventually master Sanskrit, too.

In ‘Alien Homage’, his study of his father’s relationship with Tagore, EP Thompson would suggest, with typical hyperbole, that by 1913 ‘the missionary was beginning a conversion of some sort by heathen legend, folklore and poetry’.3 It is probably more reasonable to say that Edward John had begun to consider himself a sort of bridge between Indian and English culture. It is clear that Thompson quickly lost whatever sympathy he had ever had for the Methodist vision of an Anglicised, Christian India. He did not, however, simply turn his back on British and Christian culture. Instead, he came to believe that India and Britain could complement and enrich each other. Elsewhere in ‘Alien Homage’, EP Thompson describes his father’s contradictions with more subtlety:

It proves to be less easy than one might suppose to type Edward [John] Thompson when he first met Tagore. His association with the Wesleyan Connexion was uneasy … His distaste for the introverted European community at Bankura made him eager to seek refreshment of the spirit in Bengali cultural circles, where he was even more of an outsider who sometimes misread the signals. But even if he was not fully accepted on any of the recognised circuits, he constructed an unorthodox circuit of his own … He was a marginal man, a courier between cultures who wore the authorised livery of neither.4

Thompson’s attitude may have been enlightened, by the standards of the Methodist missionary service in the second decade of the twentieth century, but it was by no means radical. An appreciation of some aspects of Indian culture did not imply opposition to the domination of Indian society by Britain. The bridge the young Thompson wanted to build would connect an imperial Britain with a political outpost of the empire. Robert Gregg has described the limits of Edward John’s enterprise:

Thompson certainly did attempt to cross boundaries and make ‘homages’ to Indians and Indian culture that relatively few Britons at the time were making … in doing so he nevertheless replicated imperial models … he was a great believer in the imperial system … 5

An aside about British intellectuals

Edward John Thompson’s optimistic liberal imperialism was hardly exceptional in the generation of British intellectuals to which he belonged. The decidedly non-revolutionary behaviour of British intellectuals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has often been remarked upon by historians and sociologists, because it seems so contrary to the mood amongst the intelligentsia of other key European countries during the same period. Russia’s intelligentsia was notorious for producing rebels and critics of society. In France, the Dreyfus affair brought intellectuals together against the government and public opinion. In France, Germany, and to an extent Russia, intellectuals formed their own institutions, which played an important role in public debates, as well as in internecine academic struggles. It is little wonder, then, that the failure of the intelligentsia to develop the institutions and self-consciousness worthy of distinct stratum of British society in the nineteenth century has also raised eyebrows amongst scholars.6

To understand the oddities of the British intelligentsia, we need to understand other peculiarities of British society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The modern British intelligentsia began to take shape in the mid-nineteenth century. Its emergence was encouraged by the growth of the British Empire and state, the expansion of the reading public, and controversy over the nature of the university system.7

The intelligentsia drew most of its members from the middle-class professions and from the prosperous petty bourgeoisie. Many of its members had nonconformist and Evangelical backgrounds. The ‘reforming’ wing of the aristocracy was represented. Intermarriage and patronage eventually led to the emergence of what Noel Annan has called an ‘intellectual aristocracy’.

Conflict provided the stimuli for the emergence of a modern British intelligentsia. The British state grew to control the consequences of industrialisation. The Foreign Service grew as inter-imperialist rivalry led Britain to take direct political control of the territories it exploited economically. The debate over the role of universities was prompted by challenges to the exclusion of non-Anglicans from Oxbridge, challenges which were part of a wider call for the reform of the British elite’s institutions by an emergent industrial capitalist class.

British capitalism was stronger than its rivals throughout the nineteenth century. British pre-eminence helped limit social and cultural conflict in British society, and is ultimately responsible for the peculiar nature of the nineteenth-century British intelligentsia.

The British intelligentsia did not enjoy a great deal of institutional and cultural autonomy – it was informally integrated with the country’s political and economic elites. The elite of the intelligentsia enjoyed an ‘Old Boys’-style relationship with the British ruling class. Old school ties, friendship and marriage were more important integrating devices than ‘public’ institutions with more or less meritocratic criteria for membership. Dissident fringes exempted, the British intelligentsia was not culturally alienated from its ruling class.

This ‘informal integration’ had its political corollary in a ‘high liberalism’ which was characterised by a belief in the progressive nature or progressive potential of British capitalism and imperialism. Economic dynamism and social cohesion made gradual social improvements possible. Intellectual influence was a matter of a word in the right ear of the elite, not a manifesto. Noel Annan summed up the peculiarities of the English intelligentsia:

Stability is not a quality usually associated with an intelligentsia, a term which, Russian in origin, suggests the shifting, shiftless members of revolutionary or literary cliques who have cut themselves adrift from the moorings of family. Yet the English intelligentsia, wedded to gradual reform of accepted institutions and able to move between the worlds of speculation and principle, was stable.8

Sheets of flame

When World War One suddenly broke out in August 1914, Edward John Thompson’s optimism and patriotism were not at first affected. Like so many young Europeans, he felt stirred to help his country’s war effort. It was not until 1916, though, that he was able to become a chaplain in the British army. He spent time in Bombay, working with the wounded in the huge army hospital there, before shipping out for Mesopotamia, where British forces were engaged in a series of campaigns against the disintegrating Ottoman Empire. Moving up the Tigris River from Basra, Thompson’s unit was caught up in some heavy fighting. Thompson’s courage under fire earned him a Military Cross. After Mesopotamia, Thompson spent time in Lebanon, where he witnessed a severe famine.9

It was while he was in Lebanon that Edward John met and courted Theodosia Jessup, the daughter of American expatriates. Theodosia and Edward John married in 1919.10 After the war, Thompson returned to Bankura College and resumed his teaching duties.11 His experiences in the army had greatly affected him, though, and they ensured that he would not stay in his old job for long. Like so many European intellectuals, Thompson had found his faith in the progressive nature of Western civilisation had been badly knocked by the years of slaughter. Edward John was angry at the sacrifice of life he had witnessed, and believed that it must have been caused by some deep failing in the warring societies. Although he lay most of the blame for the war with the German side, he did not excuse Britain from culpability. In a letter to his mother, written near the end of the war, Thompson made his feelings clear:

If I live thro this War, I will stand, firmly and without question, with the Rebels. What we need is entire Reconstruction of Society. The old order is gone, & it was inestimably damnable when here. The East does things better, in a thousand things, than we do … this war has shown with sheets of flame that the whole system of things is wrong, built on blood and injustice (emphasis in original).12

Thompson believed that events in Europe and the Middle East had endangered the British project in India, by associating the ‘advanced’ Christian civilisation Britain represented with death and destruction on an unparalleled scale. In a 1919 article for a Methodist magazine, Thompson insisted that:

The War has shocked India unspeakably, has seemed a collapse. It is felt by many that Christianity is discredited … for India now, everyone agrees, the overmastering sense and atmosphere is passionate nationalism.13

Thompson’s opinion of Indian civilisation was boosted by his partial disillusionment with the Western nations. He may well have been influenced in this respect by Tagore, who spent much ...