![]()

FOUR

MEN, WOMEN

AND GODS

This chapter will deal with one of the most important aspects of the Chedworth villa but one for which we have hardly any direct evidence from the site itself: the people who lived there and formed the household. What the chapter will do is produce a rather generic picture of what such a household might have looked like by using evidence about the late Roman aristocracy in the western part of the Roman Empire more generally and see how the evidence we have from Chedworth relates to such a picture. Due to the nature of our sources we know far more about the late Roman aristocratic male than we do about the women and children of this class. We know even less about the workers, servants and slaves who formed part of the wider familia under the control of the dominus (these last will be considered in Chapter 6). It has to be accepted from the outset that this is a speculative exercise, one which is more to do with possibilities, but occasionally probabilities.

To counter the charge that this is entirely an exercise in speculation, we shall investigate how various features of the villa correspond with how such a residence should have looked based on other sources. Much of the chapter will be concerned with the social and cultural attitudes these people held, how they were formed and how they were expressed. One area which will have touched them all deeply was religion, and the fourth century was a time of great change and turbulence as the new, imperially favoured religion of Christianity began to make inroads at the expense of the traditional religions (paganism); turbulence for which we have rare and striking evidence from Chedworth which will be looked at in the latter part of the chapter.

FAMILY AND FAMILIA

All historians and archaeologists dealing with late Roman society agree that the family was the most important social unit, providing the ‘life support system’ for the individual and in large part defining who they were. More difficult to assess is the relative importance of the ‘nuclear’ and the ‘extended’ family, but in the ancient written sources it tends to be the nuclear family unit of parents and children, plus close relatives by blood and marriage such as parents and in-laws, that constituted the most frequently encountered family unit; archaeology goes some way to supporting this with excavated dwellings of a size more suitable to this sort of unit than something larger. The extended family was also important, however, through its provision of a wider web of contacts with reciprocal bonds of support. In the Roman world this grouping of people with a shared descent in the male line constituted a gens, and at the highest social level such a gens could wield a great deal of political power through gaining high office and through its control of many lower-placed people. Familiar examples from earlier in Roman history are gentes such as the Iulii (as in Julius Caesar) or the Claudii (as in the Emperor Claudius). Even under the later empire there were still important gentes such as the great senatorial dynasty of the Symmachi. Whether there were equivalent ‘great families’ in provinces such as Britain is difficult to tell due to the lack of evidence, but there is some proof for such gentes across the Channel in Gaul, such as the Aviti of central Gaul in the fifth century. If a gens stretched through time, at any one moment what mattered was the familia, the family by blood and marriage, plus the wider household of dependents, servants and slaves.

What defined the familia was that legally all its members were under the control of the senior male, the paterfamilias, the father of the familia. This control (patria potestas – paternal power) over the persons and property of the members of the familia was far-reaching; in theory, a paterfamilias could exercise the power of life and death over members of the familia or even sell his children into slavery. While he lived he had total control over the property of his children and subordinates, who did not even escape his power by marriage; only when he died did a son in turn become a paterfamilias. Evidently, the more extreme powers were seldom exercised and by the fourth century the total power over the familia had been to some extent moderated. In return for his powers, the paterfamilias was expected to be moral, to bring up his children in the correct way and to perform the necessary religious sacrifices and rituals to preserve the favour of the gods towards his familia, particularly in the sphere of the Lares and Penates, the gods of the household, along with the gods of the gens. So the familia was more than just a legal unit; it was a cultural and religious grouping. A paterfamilias passed his property to his heirs through a will, and could allocate the inheritance as he saw fit. Primogeniture, whereby the eldest son inherited all, was not practised, though the eldest son was seen as the chief heir and became the new paterfamilias. If the paterfamilias died without making a will, the property was split equally between his children.

Within the familia the position of women was, of course, subordinate; nevertheless, they had a certain amount of independent identity. A daughter was subject to her paterfamilias; when she married she did not pass under the power of the paterfamilias of her new familia but remained under her father’s potestas. This, among other things, meant that any dowry she brought to the marriage did not pass to the new familia, since it remained the property of her father; her husband might only enjoy ‘usufruct’ (use) of the earnings of the dowry. Marriage among the aristocracy, be it senators at Rome or the aristocrats of a province such as Britain, was essentially about uniting two familiae, their property and their influence. Such marriages were ‘arranged’ with little if any regard to the feelings of the man and woman involved, though some clearly did evolve into marriages of affection and respect. Marriage was also about producing children to carry on the line.

In the Roman world, for an adult to be unmarried, particularly for a man, was highly abnormal and socially undesirable; the ideas of celibacy and consecrated virginity being developed by the Christian Church were among the more peculiar innovations of that religion in the eyes of adherents of the traditional religions. To be childless was not only a personal grief but also a social failure of a high order since it meant one’s line would die out. Not all marriages succeeded, and until the start of the fourth century either party might divorce the other, and in this case the dowry would revert to the wife’s original familia. As the fourth century wore on, divorce was made more difficult, but still existed. For a woman, though divorcing her husband might rid her of a man she could not get on with, the risk was that she would lose contact with her children, since they would remain under the paternal power of her familia by marriage: access agreements were not a feature of Roman practice. When her father died, an unmarried woman or widow acquired a measure of legal independence; she could, for instance, initiate lawsuits on her own account and could choose whom to marry. Nevertheless, she had to have a legal guardian, usually a male of the familia, appointed to act for her in other respects.

The description above is from a Roman perspective, but it must be remembered that the inhabitants of Britain would have had their own family structures, marriage practices and inheritance rules before the Romans arrived. After the conquest of Britain, the Romans did not seek to abrogate these: Roman marriage law and practice would only apply to Roman citizens, so British practices would have continued. But an edict of the Emperor Caracalla (211–218) in 212 gave Roman citizenship to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. From then on, theoretically at least, Roman marriage law and custom applied to pretty much everyone in Britain, so one could argue that the description above covers late Roman practice in Britain. It is possible, however, that family, marriage and inheritance practice in Roman Britain had been influenced by pre-existing local practice, and it may be that these forms of marriage continued in Britain as provincial variants of ‘Roman’ marriage. The problem is that we know very little about such practices.

The inhabitants of the province of Britannia are generally characterised today as Celts, meaning they spoke a Celtic language (ancestral to Welsh). Yet what Celtic social structures and practices were are very unclear. The main problem lies with the sources: either they were written from the Greek or Roman side and must lie under suspicion of wanting to tell salacious stories about barbarians (women taking multiple husbands, male homosexuality, sexual freedom of women), as contrasted with civilised Romans, or possibly misunderstanding snippets of information, rather than telling the full story; or if the sources came from the Celtic side, they came from long after the Roman period in Britain, and often from Ireland, which had never been part of the Roman Empire and which by the time the sources were written had been converted to Christianity, thus changing ideas on marriage and the family. Therefore, such sources have to be used very carefully and with a pinch of salt. Nevertheless, the picture is one of nuclear families operating within larger kin-groupings and with common lineages by descent; to a certain extent, not unlike the Roman structures. How marriage operated and the relative positions of adult males, females and children within marriage and the family is almost totally opaque to us. The later sources from Wales and Ireland show that inheritance, as with the Romans, was partible; that is, the inheritance was divided up among the heirs rather than simply passing to the eldest son.

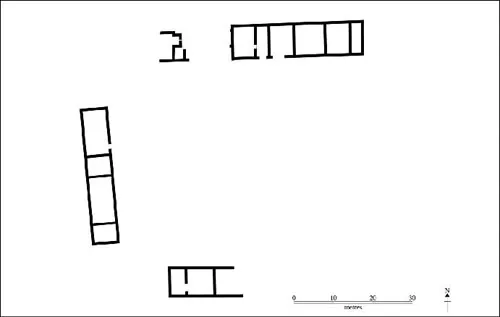

22. Plan of the ‘early villa’ as ‘unit system’. (Henry Buglass/University of Birmingham)

This question of partible inheritance has opened up a debate about the way in which some villas in Roman Britain were laid out and this has resulted in a rather different picture of their social structure and thus their layout. Instead of a villa being under the control of a single paterfamilias and inhabited by him and his familia, the proposal is that a villa was the residence of a kin group, with more than one branch of the same extended family occupying different parts of the complex, the ‘unit system’. This proposal came about because some villas seem to have more than one residential building in use at the same time; one example not far from Chedworth is the villa at Spoonley Wood, some 11km (7 miles) to the north, where as well as the principal residential range there seems to be a lesser one attached to it. The suggestion is that these two units were the residences of a senior and a cadet branch of the same family inheriting in tandem through partible inheritance. Such a scenario has also been proposed for Chedworth, suggesting that the ‘early villa’ with its separate buildings was laid out according to this social formation and so was the fully developed villa of the fourth century. According to this view, the west range and the north wing each represented a separate residence, with its own bathhouse and dining suite. This scheme of things has not won wide acceptance for three reasons: partly because the number of villas which appear to conform to this pattern is such a tiny minority that they do not offer a firm foundation for a general theory; partly because there are other possible explanations for the duplicate features such as bathhouses; and partly because partible inheritance should presumably lead over time to more than two family units within one complex. So here the discussion will accept that what we are dealing with is an aristocratic household of late Roman type. However, the existence of this debate about multiple family occupancies of villas serves as a useful reminder that we are dealing with possibilities and probabilities, not certainties. Therefore, taking the model of a familia under the control of a paterfamilias, the dominus of the late Roman household, what can we say about the principal actors at a site such as Chedworth, especially the nuclear family of husband, wife and children? It is these people, their upbringing and appearance that we shall look at next.

THE FORMATION OF A DOMINUS

The basis of status in Roman society was land and the revenues that came from that land. Entry to the two highest orders of Roman society, the senatorial and the equestrian, was conditional upon property qualifications (as well as the right moral character), as was entry to the ordo, the councils that administered the local government areas of the empire. Position was therefore dependent on inherited or acquired wealth. Inherited wealth was the most desirable since with it went noble descent. Wealth acquired through means such as army service or imperial service was acquired in an honourable fashion; wealth acquired through trade was looked down upon. So a man’s position in Roman society was traditionally determined by birth, especially if he was born into a landowning family. If born into an established aristocratic family his attitudes to private conduct and public life would be largely formed by education. The sons of the nouveau riche would undergo the same education, being trained into the accepted aristocratic mindset so that the second generation would think and act like their aristocratic friends. An example of this at the highest level is the western Emperor Valentinian I (364–375), who had risen to the purple by military ability and was ‘uneducated’, sending for the Bordeaux grammaticus Ausonius to inculcate in his son Gratian the cultural knowledge and ability and thus the attitudes proper to a high-born Roman. Valentinian knew that what distinguished a member of the upper classes from his inferiors was the fact that he had been educated. Functionally, this allowed him entry to the various professions and occupations where literacy was essential, including the local council, the law and the imperial service; culturally, literacy and the associated knowledge of the classical texts marked him out as a man of the ‘right sort’, since education was as much about the moral qualities acquired as about the things learnt.

The overall levels of literacy in the Roman world are very difficult to judge, and would have varied enormously by region, class or the occupation of a person; but it is generally agreed that the bulk of the population was illiterate, or had only very partial literacy. Thus, even to be functionally literate – that is, to be able to read and write with ease – was a rare accomplishment and one that could open many doors to social mobility in organisations such as the army, the civil service or the Church. Yet a properly educated man would have been schooled in much more than just his letters. He might have learnt his alphabet in the home, as could happen in a rich household which kept a servant or slave, pedagogus, as a sort of ‘governor’ to the children; then he would have to receive formal training. This might start at a ludus litterarius, an elementary school where the basics of literacy and grammar were imparted before moving on to the main stage of his education. Alternatively, he could omit the ludus and go straight to a grammaticus, a teacher of ‘knowledge of speaking correctly’ and ‘the explication of the poets’. Speaking correctly required knowledge of the parts of speech, how they worked and their relations. Explication of the poets involved detailed examination of the works of the approved canon of writers as examples of the correct use of language, along with the stories they related and the personalities (divine, mythical, human) involved, how they exemplified correct behaviour, plus the religious and philosophical content of the ...