- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book completely re-evaluates the evidence for, and the interpretation of, the rule of the kings of Late Iron Age Britain: Cunobelin and Verica.

Within a few generations of their reigns, after one died and the other had fled, Rome's ceremonial centres had been transformed into the magnificence of Roman towns with monumental public buildings and Britannia examines these kings' long-lasting legacy in the creation of Britannia.

Among the topics considered are:

- the links between Iron Age king of Britain and Rome before the Claudian conquest

- the creation of the towns of Roman Britain

- the different natures of 'Roman identity'

- the long lasting influence of the kings on the development of the province

- the widely different ways that archaeologists have read the evidence.

Examining the kings' legacy in the creation of the Roman province of Britannia, the book examines the interface of two worlds and how much each owed to the other.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

FRIENDLY KINGS AND GOVERNORS

As Rome grew throughout the Republic and Early Empire, so too did the length of her borders and consequently the number of her neighbours. Each new set of peoples brought with them their own diplomatic challenges. Often Rome formed alliances and friendships with the polities around her. This dialogue between mainly unequal partners was part of the natural strategy of defence that many states have engaged in since time immemorial, protecting their own economic and territorial interests. Tools used in such strategies vary: they might include dynastic marriages, treaties, military assistance, and the education of the satellite state’s elite at home schools or universities, creating that all-important network of friends amongst the international political elite. The purpose of all of these was to foster trade and exchange, and gain political dominance, without the necessity of engaging in too much military activity. We might choose to call these smaller territories satellite states, allies or client kingdoms depending on their time and place in world history, but all lived in the shadow of greater powers.

Rome’s interest in her neighbours has many echoes down the centuries. The modern era has been full of such examples. As the Ottoman Empire declined, the British and French (and later Americans) courted sheikhs likely to prove pliable and friendly to their political interests. Many were supported or installed in their capitals by these foreign interests. Their sons came to be educated in western schools and military academies, recasting their minds with a European outlook. Returning to inherit their kingdoms, these westernised monarchs had a careful balancing act to perform, culturally imbued with a mixture of western and near eastern mores. Those successful at this were exemplified by characters such as King Hussein bin Talal of Jordan (1935–99), educated at Harrow public school and Sandhurst Military Academy. Back in Jordan, when he succeeded his father, Hussein managed to negotiate a number of coups and assassination attempts. He placated rising nationalist support by ditching his commander-in-chief, a British general, who had in many ways been a symbol of Jordanian dependence upon Britain and the west. None the less, throughout his long reign, he managed to tread that fine line of maintaining western acceptability in the face of remarkably difficult circumstances, namely the Israeli and Palestinian conflict, the six-day war, and relations with Iraq. Of his four wives, one was British, while his last, Queen Noor, was American. His son and successor, King Abdullah, continues the linkage, educated at St Edmund’s School, Surrey, then at Eaglebrook School and Deerfield Academy in the United States, before returning to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst and Oxford University in the United Kingdom. However, for every successful leader, brought up and inculcated with the values of whichever world power is dominant at the time, there are other unsuccessful ones, unable to maintain the balancing act. Some nominee leaders imposed from outside may just never be acceptable to the native inhabitants. One example was the attempt to make Ahmed Chalabia leader in post-Saddam Iraq. He had been part of the leadership of the Iraqi National Congress, an opposition group in exile created at the behest of the US government. However, after the 2003 Iraq War it became clear he had little local backing and his influence with the Americans rapidly waned. Others fared better for a while, but ultimately failed. The last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1919–80), gained the throne during the Second World War when Britain and Russia grew concerned his father was about to align the country and its oil reserves with Germany and forced his abdication. Social unrest saw the new Shah’s removal in 1953, but the British SIS and American CIA sponsored a coup that saw his return, whereupon he managed to survive through the use of increasingly autocratic rule until the Iranian revolution of 1979. By the end of his reign he too had lost the sympathy of his population and original international backers. It all goes to show, selecting rulers for other peoples’ countries could be a pretty hit or miss affair, which sometimes worked, but at other times stored up trouble for the future, as one-time friends fell from grace.

The Roman world was not much different. Occasionally, in the heyday of the Republic, members of royal dynasties would be sent to Rome or spend time with her armies developing the link between them and the aristocracy of the Republic. Jugurtha was one such example, sent away from his homeland to fight with the Roman legions in Spain in the late second century BC. His uncle, the king of Numidia, was so impressed by reports of his nephew that when Jugurtha returned he was made the king’s heir. Indirectly, Rome had affected the succession of a neighbouring state. It had also trained up someone in the latest techniques of military warfare who would one day turn that learning back on his tutors. By the late first century BC this interference in the affairs of friendly kingdoms became far more intrusive and deliberate. So much so, that whereas under the Republic we find heirs to a throne acceding and then asking for recognition from Rome, by the time of Augustus and his successors we find the Princeps actually appointing the successors himself.

The vast majority of these kingdoms known from literary sources were in the Hellenistic territories of the East. Many of the monarchs of these realms sent some of their children to Rome as obsides. This is a term often translated into English as ‘hostages’, but this gives a very negative view of the relationship between the child and Rome. While in the metropolis these princes grew up and were educated in Roman mores, they developed friendships, amongst Romans and other obsides alike, that would assist them later in life when they became major players in the geo-politics of the Mediterranean world. Rome benefited, but so did the incumbent kings. Potential successors at home could foment intrigue at court; having their sons many miles distant in Rome could have advantages to the monarch. This phenomenon, which significantly developed in the early Principate under Augustus, did not just enhance the relationship between centre and periphery; it also bonded together the territories around the edge of the Roman world as personal friendships were cemented with political marriages. Suetonius’ description of this practice is so clear that it deserves repeating:

Except in a few instances [Augustus] restored the kingdoms of which he gained possession by the right of conquest to those from whom he had taken them or joined them with other foreign nations. He also united the kings with whom he was in alliance by mutual ties, and was very ready to propose or favour intermarriages or friendships among them. He never failed to treat them all with consideration as integral parts of the empire, regularly appointing a guardian for such as were too young to rule or whose minds were affected, until they grew up or recovered; and he brought up the children of many of them and educated them with his own.

(Suet. Aug. 48)

It is an unproductive argument to discuss whether friendly kingdoms were part of the Empire or not. It is largely a matter of semantics. At times these kings could be viewed in effect as imperial administrators, a phenomenon which would be ‘entirely in keeping with [Rome’s] general tendency to concede and encourage considerable local autonomy throughout her empire – most notably through cities – and thus pass to others the burden of day-to-day administration’ (Braund 1984:184). At other times they could be viewed as very much outside Roman dominion.

All too often the relationship with Rome is imagined as oppressive or domineering; but that is to forget the authority and power that Roman support gave to a king. Both sides benefited from the association. On Rome’s side, when it worked, a measure of control and stability was achieved around its provinces. It also created a military reserve, which could be called upon at times of crisis. On the king’s side, the relationship might involve receiving ‘subsidies’ from Rome to help him maintain his position, while conferring prestige upon the monarchy under many, though by no means all, circumstances. Association with knowledge from distant lands could often be seen as attractive and empowering (Helms 1988), but there was a fine line; too much could become alienating to the local population. In such cases if the ruler’s position at home became weakened, the relationship could provide the ultimate sanctioning of force to support the monarch’s rule with the help of Roman legions or auxilia.

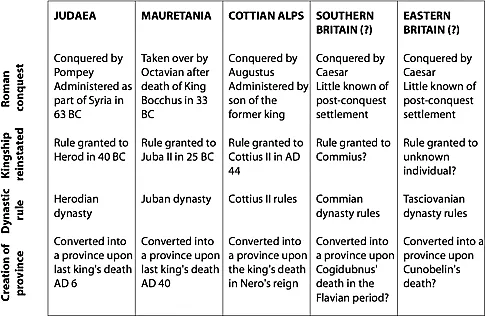

These kingdoms underwent various transformations as political events took their course. Some might remain as ‘buffer states’ between Roman and other competing powers, such as Parthia in the East. Some upon the death of the king were converted into a full Roman province and given not a new monarch but a governor. However, in the Julio-Claudian period, Rome could just as easily convert provinces into kingdoms as the other way around if expedience demanded it. These kingdoms existed in a liminal state of flux, illustrated by three examples from around the time Rome began to get interested in Britain.

First, Judaea was originally captured by Pompey, and instead of immediately granting royal title of the area to Hyrcanus II, it was decided that the territory should be directly administered as part of the neighbouring province of Syria. This situation lasted for a generation from 63 to 40 BC. Then the region was converted back into a kingdom under the rule of the Herodian dynasty. When Herod the Great died in 4 BC he had been awarded by Augustus the rare privilege of appointing his successor. In his final will he had selected Archelaus, but Augustus demoted his title from king to that of ‘ethnarch’ or ‘national-leader’. Archelaus lasted until AD 6 when Augustus sent him into exile at Vienne in Gaul after complaints about his rule by both Jews and Samaritans. Thereafter Judaea reverted to provincial status, with governors such as Coponius (AD 6–9) and Pontius Pilate (AD 26–36/7) given to the territory. Briefly, from AD 41 to 44, it had a king again under Herod Agrippa, after he had assisted Claudius to the throne, but upon his death his son Julius Marcus Agrippa was deemed too young to replace him, so Claudius turned Judaea back into a province (Kokkinos 1998). Clearly it would be difficult to pin down one date when Judaea became ‘Roman’.

Secondly, much of Mauretania (modern Morocco and part of Algeria) was a friendly kingdom under Bocchus. However, after Bocchus’ death in 33 BC Octavian took control of the country, issuing his own coinage there. In the next few years colonies of retired veterans were planted throughout the territory (Mackie 1983). Then in 25 BC Augustus, as he was now called, resurrected the Mauretanian throne and granted it to Juba II, son of the former king of neighbouring Numidia. The restored kingdom lasted for two generations until AD 40, when Juba II’s son and successor, Ptolemy, was imprisoned and murdered on the order of the emperor Gaius. After this two new provinces called Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Tingitana were created out of the kingdom early in Claudius’ reign (Fishwick 1971; Roller 2003). Again, it would be difficult to select one iconic date when Mauretania became ‘Roman’.

Figure 1.1 Conquests, friendly kingdoms and provinces

Finally, this state of flux did not just occur at the frontiers, but also in areas totally surrounded by provinces. When Augustus conquered the Cottian Alps, the son of King Donnus became the Roman official in charge of the region, ruling as a prefect. He, like his father, was a Roman citizen as well as of royal birth. In AD 44 Claudius converted the territory back into a kingdom, granting Donnus’ grandson, Cottius II, the title king, along with additional tracts of land (Braund 1984:84). However, upon his death in Nero’s reign the area reverted to provincial status.

Kingdoms and provinces can, at times, appear almost interchangeable, and this is also reflected in similarities between the roles of governors and monarchs. Both sets of individuals knew each other well; the governors of the neighbouring provinces would be the most immediate points of contact for kings after all. Thus not only did the sons of monarchs visit Rome, but the sons of Romans visited monarchs:

there was regular contact between neighbouring kings and govern ors and their respective followers. Cicero’s son and nephew were conducted to stay at Deiotarus’ court in Galatia by the king’s hom onym ous son. Similarly, the young Caesar stayed at the Bithynian court and the son of Cato Minor at the Cappadocian. Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia was particularly eager to place his son under the wing of Cato himself.

(Braund 1984:16)

The relationship between the two worked in both directions. Kings adopted various trappings and symbols of authority used by governors (as we shall see below – chapter 2), while a governor could assume the cultural associations of former monarchs in their province. This is illustrated by two examples. First, a governor might symbolically represent the continuity of power by occupying the former royal residence. This certainly happened in Sicily where the governor resided in Syracuse. Secondly, while in Mauretania, the governor Lucceius Albinus in AD 69 was alleged to have assumed the very name of Juba (the dynasty he was replacing) and to have adopted the dynasty’s royal insignia. Whether or not the allegations were true, their very currency goes some way to blurring the distinctions between king and governor (Braund 1984:84). Both were also subject to replacement by the Princeps; while citizens occasionally complained about their governors to the emperor, so too could subjects about their king.

Enough will have been said to introduce the notion of friendly kings in the late Republic and early Principate. However, many of these references relate to Hellenistic kingdoms; only a few hitherto have related to the West, and none to Britain. It is now time to turn to Britain to see how a knowledge of this phenomenon helps us, with the archaeology, to reread the historical fragments that have come down to us, to understand the political transformation from the Late Iron Age kingdoms to the province of Britannia.

The situation in Britain: a brief narrative

Throughout the 50s BC, Julius Caesar was engaged in a series of conflicts across Gaul that saw the incorporation of that territory into the Roman world. During this time he made two ‘expeditions’ to Britain, where he described the Britons as being defeated, coming to terms, submitting hostages and agreeing to pay tribute. However, in the aftermath of the Roman civil war we find that whereas northern Gaul had been regularised into three provinces and the army had occupied the Rhineland, Britain appears to have been left alone. The consequence of this (and other reasons explained in the introduction) was that the exploits of Caesar in this country have been conventionally minimised in modern representations of British history. Salway (1981:37) described the expeditions as ‘Pyrrhic victories’, and with good reason; the evidence from archaeology appears to suggest a large degree of continuity either side of Caesar’s campaigns. Certainly things were c...

Table of contents

- CONTENTS

- FIGURES

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- NOTE ON TRANSLATIONS USED

- INTRODUCTION: WRITING HISTORY

- 1 FRIENDLY KINGS AND GOVERNORS

- 2 THE TRAPPINGS OF POWER

- 3 FORCE, VIOLENCE AND THE CONQUEST

- 4 THE IDEA OF THE TOWN

- 5 THE CREATION OF THE FAMILIAR

- 6 THE CREATION OF ORDER

- 7 THE MEMORY OF KINGS

- CONCLUSION

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Britannia by John Creighton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.