![]()

1

A Matter of Life and Death

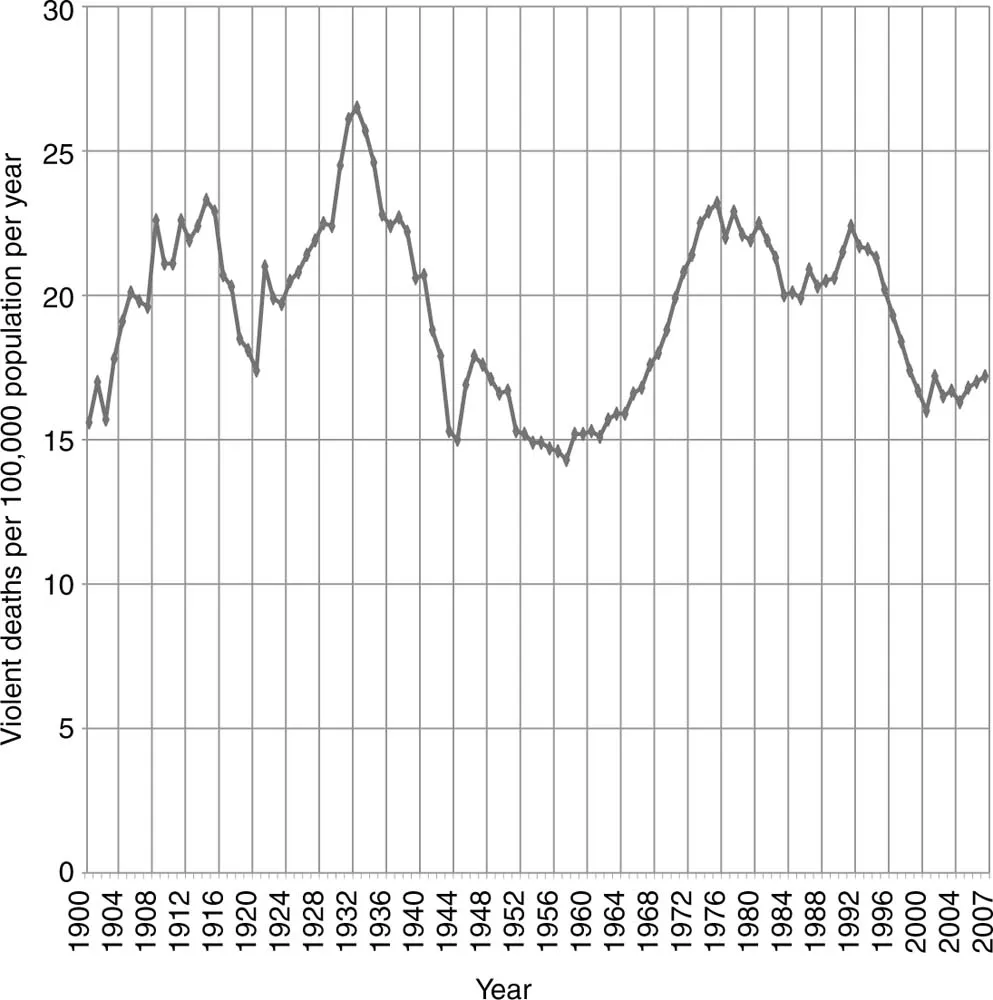

For the first 13 years of the twentieth century, from 1900 through 1912, the presidents of the US were Republicans: McKinley, Teddy Roosevelt, and Taft. In 1913, Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, took office and held it for the following eight years, through 1920. The graph in figure 1.1, illustrating the rate of lethal violence in the US from 1900 to 2007, shows a line beginning in 1900, at which time the violent death rate (the sum of suicide and homicide rates) was 15.6 for every 100,000 people per year. It is important to add at this point that these violent death rates are “age adjusted,” meaning that the proportion of people in different age groups is held constant because mortality rates are so influenced by age, with homicide rates being commonest among young adults and suicide rates highest among the elderly. Age adjusting is a means of holding the age distribution within the population constant, so that variations in death rates are not merely an artifact of changes in the proportion of the population that falls within the most vulnerable age groups. This is important in vital statistics for the same reason that holding the value of the dollar constant so as to adjust for inflation is important in economic statistics. It means that the changes in the vital statistics that are shown on the graph are not simply artifacts, or side-effects, of the post-World War II “baby boom,” for example.

Figure 1.1 Violent Death Rates (Suicide plus Homicide) per 100,000 per Year, United States 1900–2007 Age-Adjusted to Standard Year 1940 (Not Based on all 48 States until 1933)

Sources: D.L. Eckberg, “Estimates of Early Twentieth-century U.S. Homicide Rates: An Econometric Forecasting Approach,” Demography, 32: 1–16, 1995; Paul C. Holinger, Violent Deaths in the United States, New York: Guilford Press, 1987.

To return to the graph, the line, beginning at 15.6 in 1900, then rises in a steep, upward slope, increasingly steadily, making an especially large jump after the (financial) Panic of 1907, and by 1908 and 1911 reaches peaks of 22.6 violent deaths per 100,000, 50 percent higher than where it began in 1900. Thus we see that during the period 1900–12, when Republicans occupied the White House, lethal violence escalated from non-epidemic to epidemic levels. To make it clear what we are talking about, each one point increase in lethal violence signifies 3,000 additional deaths at today’s US population level of approximately 300 million, so an increase from 15.6 to 21.9 between 1900 and 1912 corresponds to what today would be an increase of about 18,900 additional violent deaths – per year.

Following Woodrow Wilson’s accession to office in March 1913, the rate continued at its epidemic level for the first year, peaking at 23.3 in 1914, his second year in office, and then began an abrupt, steep, and consistent year-by-year decline throughout the last six years of his presidency (well before, during, and after America’s brief participation in World War I), until it bottomed out at a rate of 17.4 by Wilson’s last full year in office (1920). In short, the years of Republican presidents were associated with a rise in lethal violence to epidemic levels, and the switch to a Democratic president was associated with a reversal of this trend, ending the epidemic.

But the reversal was short-lived. For the next twelve years, Republican presidents (Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover) occupied the White House, and, as figure 1.1 shows, the violent death rate escalated into the epidemic range again, beginning in the first year of Harding’s administration, and remained in a “mountain (epidemic) range” for the entire 12 years the Republicans occupied the White House, with increases almost every year after 1923, their third year in power. That steep upward climb continued until it peaked at the record high of 26.5 violent deaths per 100,000 by 1932, the last full year in which Republicans were in office. It is worth noting that the upward climb began long before the onset of the Great Depression in 1930. The violent death rate had already increased from the low of 17.4, which the Republicans inherited from Wilson’s last year in office, to 22.3 by 1929. It continued to rise further, and even more steeply, during the first (and worst) years of the Depression, finally peaking at the record high of 26.5 – a full 9.1 more violent deaths per year for every 100,000 people than during Wilson’s last year in office. To give you a sense of the magnitude of that increase, at today’s population level, this would amount to an increase of 27,300 additional suicides and homicides per year. Thus the second epidemic of lethal violence also occurred following the election of a Republican to the presidency, and continually increased in magnitude from that time, 1920, through 1932, the last year of Republican hegemony before they were replaced by a Democrat.

In 1933, Franklin Roosevelt began the first of what would become twenty uninterrupted years of Democratic presidents. In 1945, Truman succeeded Roosevelt, remaining in office through 1952. In fact, Democrats controlled the White House for 28 of the 36 years from 1933 through 1968, with Kennedy and Johnson in power during the last 8 of these years. Only one Republican president, Eisenhower, occupied the White House (from 1953 through 1960) during that period. Although Eisenhower was a Republican, he is the only Republican president who did not increase violent death rates significantly after coming to office. Essentially, they remained at the same level as they had been under the Democrats who preceded him.

What is most remarkable about this period from the standpoint of our mystery, is that the 20 years – and even the 36 years – following Roosevelt’s election to office ushered in the longest “valley” – the longest uninterrupted period of freedom from epidemic levels of violence in the twentieth century. As you can see from the graph, the violent death rate began an abrupt, steep, and almost uninterrupted decline, beginning in Roosevelt’s first year in office (1933), starting from the level of 26.5 violent deaths per 100,000 population that he inherited from his Republican predecessors and by 1941, the last year before America entered World War II, dropping below the epidemic floor of 19 to a rate of 18.8. From 1941 through 1969, the violent death rate did not once climb back into the epidemic range of 19–20 or more. Indeed, for a full quarter of a century, from 1942 through 1967, it did not reach as high as 18 again.

To clarify how I am using the term “epidemic,” I calculated both the mean and the median of the violent death rates throughout the past century, which were 19.4 and 20 respectively, and I use the term “epidemic” to refer to death rates that are unusually high, or in other words above the average (mean or median) level. Thus when I speak of epidemics I will mean those violent death rates that fall within the range of 19.4 or 20 to 26.5, the latter being the highest level reached over the past century. Non-epidemic rates, conversely, will mean those that range from 11 to 19.4. (Almost all of these rates have remained well above 20 during the periods I am calling epidemics, and well below 19.4 during the period I am calling “normal,” so it makes little difference whether we consider 19.4 or 20 to be the approximate point of transition between the “mountain range” and the “valley.”)

To summarize thus far, the three Republican presidents who preceded Roosevelt presided over an epidemic of lethal violence, just as Wilson’s three Republican predecessors had. Roosevelt, like Wilson, ended the epidemic; and violent death rates continued to remain below the epidemic range under his Democratic successors.

Let me take a moment to emphasize again that, although the numbers themselves may appear small (an increase in a death rate from, say, 15 to 20 per 100,000 people per year, or even from 18 to 19, may sound like an increase of only 1 death, or 5), at today’s US population level of 300 million people, each single digit increase in the death rate signifies 3,000 additional violent deaths per year. When one considers that that is almost exactly the same as the number of people who were killed on 9/11/2001, and that those 3,000 deaths changed history, becoming the rationale for two wars in which the United States is still engaged, these figures are not trivial.

So far, then, we have covered the first two of the three epidemics of lethal violence that occurred between 1900 and 2007. We noted that both began during Republican presidencies and ended during Democratic ones. The first epidemic began in 1905, in the middle of Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency – during and following which the death rate increased from 15.6 to 21.9 – and ended when Wilson came to power in 1913, reaching a low of 17.4 by his last year in office. Another twelve years of Republican presidents, beginning in 1921, witnessed steep year-to-year increases in the death rate, which reached a new and record-high epidemic level of 26.5 by 1932 – the highest of the century, in fact. This was then reduced under Roosevelt to 15 by 1944, showed a brief uptick (though still well below epidemic levels) after the end of the war, as usually happens when major wars end (as I will discuss below), and then resumed its decline back to its 1944 level of 15 by 1951 and 1952, Truman’s last two years in office. The violent death rate remained below epidemic levels not only throughout Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s last two terms in office, but also during the entire administrations of Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson.

However, once Johnson was replaced by the Republican Nixon in 1969, the rate quickly climbed again into the epidemic stratosphere for the third time in the century. It began increasing from the first year of the Nixon administration; rose above the epidemic “floor” by his second year in office, 1970, when it reached 19.9; and continued increasing year after year to 23.2 by 1975. It remained in the epidemic range of 21.9–22.9 during the Democrat Carter’s four years in office, 1977–80, and continued at epidemic levels of 19.9–22.4 under the Republicans Reagan and Bush Sr., from 1981 through 1992.

When Clinton took office in 1993, having inherited a violent death rate of 21.7 from his Republican predecessor, the first President Bush, the violent death rate began a steep and consistent decline year after year, dropping below epidemic levels (to 18.3) by 1997, the first year of his second four-year term in office, until by his last year in office (2000) it had fallen to 16. Republicans had been in power during 20 of the 24 years between 1969 and 1993. And it was not until a Democrat, President Clinton, became elected for two terms in office that the third and longest lethal violence epidemic of the twentieth century, one that lasted for 28 years (1970–97), finally ended.

The moment a Republican president, George Bush Jr., succeeded Clinton in 2001, the dramatic decline in lethal violence that had occurred under Clinton abruptly ended and reversed itself as the death rate began drifting upward again. By 2007, the last year for which there are comparable data, it had reached 17.2.

To sum up: as the graph in figure 1.1 shows, there were three epidemics of lethal violence in the twentieth century, all of which began under Republicans and all of which ended under Democrats. It took them a while, even with steady, uninterrupted declines year after year, but Democrats ended these epidemics by 1918, 1941, and 1997. The epidemics lasted from 1904 to 1917, 1921 to 1940, and 1970 to 1996, a total of 61 years. And there were three periods during which violence resided in the “valley” range, below epidemic levels, 1918–20, 1941–69, and 1997–2007, all of which began under Democrats (in 1918, 1941, and 1997) and lasted a total of 43 years. The first two of those non-epidemic ranges ended once Republicans returned to power. It is too early at this point to say whether the current non-epidemic violent death range will have ended by the last year of Bush Jr.’s administration in 2008, since we do not yet have comparable data beyond the year 2007. What we do know is that both violent death rates, suicide and homicide, abruptly discontinued the yearby-year decline they had shown under Clinton, and once again began increasing as soon as Bush took office.

Although the violent death rate in America continued falling after the US entered the Second World War1 in the closing days of 1941, the decline had begun long before that, descending from 26.5 in 1932, the Republicans’ last year in office, to 18.8 by 1941, and had thus fallen below epidemic levels before the US had entered the war. The rate of lethal violence (homicide and suicide), then continued to fall during the war years, reaching a low of 15 by 1944, at the height of the war. But it then remained within roughly that same range or lower, from 14.3 to 15.9, for 14 post-war years (1951–64), during the presidencies of Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson. Thus the war itself neither ended the epidemic levels of violence that Roosevelt had inherited from his Republican predecessors – they had already ended before the war began – nor led to either a major or a prolonged increase in lethal violence during the postwar years. Although there was a brief uptick in lethal violence rates following the end of the war, in 1945 and 1946, to as high as 16.9 (still well below epidemic levels), they then began falling again the following year, reaching lows of 15.3 and 15.2 by 1951–2, the last years of Truman’s presidency, thus returning to the same level as their lowest point during the war. They remained in this same low range during the next 12 years, reaching a record low of 14.3 in 1957.

Except for under Eisenhower, violent death rates during all Republican administrations either rose substantially above those inherited from their predecessors or remained within an inherited epidemic range. While this single exception distinguishes Eisenhower’s presidency (1953–60) from those of the 11 other Republican presidents since 1900, it does not contradict the general observation that rates of lethal violence rise to epidemic levels only under Republican presidents. With Ike, they did not rise but remained in roughly the same range as during Truman’s last year in office, from slightly below to slightly above 15, and ended only insignificantly (0.1) higher than they had been under Truman.

Death rates from suicide and homicide ranged from 15.1 to 15.9 through Kennedy’s three years in office and Johnson’s first year. There was then a rise, although not to epidemic levels, during the last three years of the Johnson administration, with the lethal violence rate reaching 18 during Johnson’s last year in office (1968) for the first time since 1941. From the point of view of the mysterious association between epidemics of lethal violence and Republicans in the White House, the most relevant point about that increase is that the rate of lethal violence under Johnson, even at its highest, remained below the epidemic levels that followed once this 36-year Democratic-dominated period of relative non-violence ended and was replaced by 27 Republican-dominated years marked by an uninterrupted epidemic of violence (1970 through 1996).

The 1968 election constituted one of the major electoral realignments of the twentieth century, comparable to the 1920 (post-World War I) election that led to 12 years of Republican presidencies which culminated in the Great Depression and the highest lethal violence rates of the century, and to the 1932 election that led to 36 years of what has been called the New Deal Agenda (to which the nominally Republican President Eisenhower subscribed whole-heartedly). The year 1968 was the one in which the Republicans’ “Southern strategy” – i.e., the appeal to white racial prejudice and the white backlash against the gains of the civil rights movement – resulted in the radical transformation of the 11 former Confederate southern states and two border states (Kentucky and Oklahoma) from almost uniformly Democratic to almost uniformly Republican in their political affiliations and voting patterns. This in turn brought the Republican party back into control of the White House for 20 of the next 24 years. What followed was the longest epidemic of lethal violence in the history of the past 107 years, lasting for 27 years from 1970 through 1996. The rates of suicide and homicide increased steadily during every year of Nixon’s 6-year presidency, crossing the threshold into epidemic levels by his second year in office, when they reached 19.9, and continuing to a high of 23.2 by Ford’s first year as president.

Another Democrat, Jimmy Carter, who succeeded Ford in 1977, was the only one of the seven Democratic presidents of the twentieth century under whom an inherited epidemic of lethal violence did not fall below epidemic levels. Instead, the epidemic levels of suicide and homicide he inherited from his Republican predecessors were basically unaffected one way or the other by his presidency, with both rates remaining at epidemic levels during his term in office, just as they had under Nixon and Ford. It is important for our purposes here to stress that the Carter administration did not initiate an epidemic level of lethal violence (no Democrat ever has), but he was alone among Democrats in not reversing the epidemic he inherited. The fact that he was in the White House for only four years does not alone explain the persistence of the epidemic under his administration since all of his Democratic predecessors (like Clinton later in the century) began reversing the epidemics they had inherited from their Republican predecessors early in or at the very start of their first terms in office – with lethal violence rates then declining consistently year by year. During the administrations of the two Republicans who followed Carter, Reagan and Bush Sr., violent death rates, although they fluctuated up and down from 19.9 to 22.4, never dropped below epidemic or mountain range levels during this 12-year period (1981–92).

To recapitulate, when Bill Clinton assumed power in 1993, he inherited a violent death rate of 21.7 from the first President Bush. During Clinton’s first year in office, violent death rates began a steep and steady yearby-year decline, finally reaching a level that was below the epidemic floor of 19 by the beginning of his second term in 1997. In other words, it took four years of continuous declines to end the epidemic levels of violence inherited from the Republicans. Following that, the death rates continued to drop, reaching a low of 16 by 2000, his last year in office. The moment Bush Jr. took office in 2001, this dramatic decline abruptly stopped and reversed direction, beginning a slow and fluctuating upward climb. Since we have definitive data only through 2007, we cannot yet assess the full effect of the Bush presidency on rates of lethal violence in the US. At the...