eBook - ePub

Urban China

About this book

Currently there are more than 125 Chinese cities with a population exceeding one million. The unprecedented urban growth in China presents a crucial development for studies on globalization and urban transformation. This concise and engaging book examines the past trajectories, present conditions, and future prospects of Chinese urbanization, by investigating five key themes - governance, migration, landscape, inequality, and cultural economy.

Based on a comprehensive evaluation of the literature and original research materials, Ren offers a critical account of the Chinese urban condition after the first decade of the twenty-first century. She argues that the urban-rural dichotomy that was artificially constructed under socialism is no longer a meaningful lens for analyses and that Chinese cities have become strategic sites for reassembling citizenship rights for both urban residents and rural migrants.

The book is essential reading for students and scholars of urban and development studies with a focus on China, and all interested in understanding the relationship between state, capitalism, and urbanization in the global context.

Based on a comprehensive evaluation of the literature and original research materials, Ren offers a critical account of the Chinese urban condition after the first decade of the twenty-first century. She argues that the urban-rural dichotomy that was artificially constructed under socialism is no longer a meaningful lens for analyses and that Chinese cities have become strategic sites for reassembling citizenship rights for both urban residents and rural migrants.

The book is essential reading for students and scholars of urban and development studies with a focus on China, and all interested in understanding the relationship between state, capitalism, and urbanization in the global context.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

1

China Urbanized

THE RISE OF CHINA

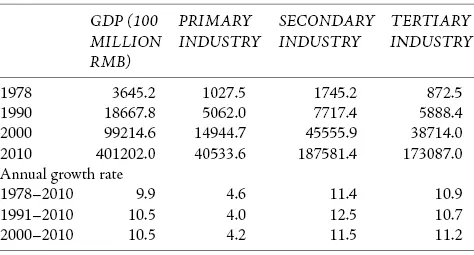

In 1978, when Deng Xiaoping, the chief architect of China’s market reform, returned to leadership after the Cultural Revolution, China was still a backwater – a developing society with a large rural population, an outdated manufacturing sector, and dilapidated housing stock and infrastructure in urban areas. After three decades of market reform, China surpassed France in 2005 and Germany in 2007 to become the third largest economy in the world. And merely three years later, in 2010, China finally overtook the economic powerhouse of Japan, and became the second largest economy next to the United States. From 1978 to 2010, China’s GDP grew at 9.99 percent per year on average, which was the highest continuous growth rate among the world’s nations (tables 1.1 and 1.2). Its per capita GDP in 2010 was 29,992 RMB (about 4,837 USD), 79 times higher than in 1978 (about 61 USD) when the reform began.1 Although the benefits of the market reform are unevenly distributed, the continued economic growth has nevertheless lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty, and China has finally joined the league of middle-income countries.

Table 1.1: China’s GDP growth rates, 1978–2010

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 2011, www.stats.gov.cn

| GDP GROWTH RATES (IN %) | PER CAPITA GDP (IN RMB) | |

| 1978 | 11.7 | 381 |

| 1979 | 7.6 | 419 |

| 1980 | 7.8 | 463 |

| 1981 | 5.2 | 492 |

| 1982 | 9.1 | 528 |

| 1983 | 10.9 | 583 |

| 1984 | 15.2 | 695 |

| 1985 | 13.5 | 858 |

| 1986 | 8.8 | 963 |

| 1987 | 11.6 | 1,112 |

| 1988 | 11.3 | 1,366 |

| 1989 | 4.1 | 1,519 |

| 1990 | 3.8 | 1,644 |

| 1991 | 9.2 | 1,893 |

| 1992 | 14.2 | 2,311 |

| 1993 | 14.0 | 2,998 |

| 1994 | 13.1 | 4,044 |

| 1995 | 10.9 | 5,046 |

| 1996 | 10 | 5,846 |

| 1997 | 9.3 | 6,420 |

| 1998 | 7.8 | 6,796 |

| 1999 | 7.6 | 7,159 |

| 2000 | 8.4 | 7,858 |

| 2001 | 8.3 | 8,622 |

| 2002 | 9.1 | 9,398 |

| 2003 | 10.0 | 10,542 |

| 2004 | 10.1 | 12,336 |

| 2005 | 11.3 | 14,185 |

| 2006 | 12.7 | 16,500 |

| 2007 | 14.2 | 20,169 |

| 2008 | 9.6 | 23,708 |

| 2009 | 9.2 | 25,608 |

| 2010 | 10.3 | 29,992 |

Table 1.2: Shares of GDP and annual growth rates for primary, secondary, and tertiary industries, 1978–2010

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 2011

Note: Data are calculated at current prices.

China’s economic rise has presented an interesting puzzle for social scientists, and scholars have been debating why the country has grown so fast in a relatively short period of time. Two different, but complementary, perspectives can be observed in the debate on China’s rise. The first views China’s extraordinary growth as part of the worldwide trend of neoliberalization that began in the late 1970s. It relates China’s reform measures to marketization and privatization processes taking place in other parts of the world, and sees China’s rise as a part, but also a result, of the neoliberal economic restructuring globally (Harvey, 2005). The second view is more attuned to the Chinese historical-local context, and takes China’s socialist legacies and post-socialist institutional arrangements as the foundation of the country’s spectacular growth (Arrighi, 2007; Huang, 2008).

The first perspective, which explains the rise of China in relation to worldwide neoliberalization, can be further divided into two camps – the promoters and the critics of neoliberalism. According to David Harvey, neoliberalism refers to the political economic proposition that individual freedom and well-being can be best achieved by free markets, free trade, and private property rights, and that the role of the state is to provide institutional frameworks to facilitate free markets and trade and to protect private properties and profit-making activities (Harvey, 2005). Both the promoters and the critics of neoliberalism view China’s rise as part of worldwide neoliberalization, but they offer very different explanations of the actual nature of China’s adherence to neoliberal doctrines.

The promoters of the free market, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), often spread the view that China has been on the fast track of economic growth because the country has adhered to neoliberal policy prescriptions such as privatization, deregulation, and decentralization of fiscal resources and decision-making power from the central to local governments. They believe that with a more open market, a more developed private sector, and a stronger regime of private property rights, eventually the benefits of the market reform will trickle down to the masses. This position, however, is simply not supported by empirical evidence. The economies of a number of Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Argentina, and Jamaica, were devastated after their governments followed structural adjustment policies prescribed by the IMF that included devaluation of currencies, decreases in workers’ wages, reduction of social expenditures, privatization of state enterprises, and the opening up of the domestic economy to foreign investment. China’s reform measures little resembled these shock therapies. All of these processes happened in China, to a certain degree, but they took place over a longer time period – the reform has continued over a period of more than three decades, and the practice of privatization and deregulation has always been highly selective so that the destructive effects of these market reforms are minimized and delayed.

The critics of neoliberalism question the exploitative growth path China has taken, censuring the current polarization of Chinese society, as evidenced by the widening gaps between the rich and the poor, urban and rural residents, and coastal regions and the hinterland (Harvey, 2005; Arrighi, 2007). Although they do not necessarily think that China’s reformers, such as Deng Xiaoping, used the prescriptions of the World Bank or the IMF to guide their actions, they interpret the key reforms China has made, in the sectors of land, housing, and state-owned enterprises, as clear evidence of privatization and deregulation similar to what happened in the West in the 1970s, Latin America in the 1980s and Eastern Europe in the 1990s. For example, David Harvey writes that “the outcome in China has been the construction of a particular kind of market economy that increasingly incorporates neoliberal elements interdigitated with authoritarian centralized control,” and he calls this unusual mix of neoliberal elements and authoritarianism “neoliberalism with Chinese characteristics” (2005: 120). He further argues that the market reform in China exemplifies a process of “accumulation by dispossession” – of farmers, urban workers, and migrants – and reconstitutes class power, as evidenced by the sharp increase in income inequality, just like that in the US, the UK, and Latin America.

The critics of neoliberalism are right to point out that China’s success story is inseparable from the worldwide neoliberalization that opened up space for China to be integrated into the world economy, and that China has turned from an egalitarian society into a highly polarized one. However, the broad-brush interpretation and categorization of China’s reform as an example of generic neoliberalization does not help explain why China has, over such a short period, become the second largest economy in the world, and why other emerging economies such as India, Russia, and Brazil, which also neoliberalized, have not grown at a similar pace.

The second camp of political economic analysis traces China’s rise to context- and history-specific conditions and institutional innovations. For example, Giovanni Arrighi identifies two conditions that laid the foundation for what he calls the “Chinese ascent” (Arrighi, 2007). The first is the result of the social legacies of the Chinese revolution and three decades of socialism. Arrighi argues that by the late 1970s China was in a better position to launch its reform than other developing countries such as India, because socialism had delivered high literacy rates, good education, and a long adult life expectancy, and therefore China’s labor force was relatively healthy and well educated at the dawn of the reform. China’s booming export sector benefited greatly from the country’s cheap labor, but Arrighi emphasizes that it was not just the low cost, but also the education and health of the labor reserve that marked a difference from other developing countries and attracted foreign investment.

Second, the early success in rural sectors of Township and Village Enterprise (TVE) initiatives laid firm foundations for the economic take-off later. Deng Xiaoping’s reform targeted the agricultural sector first. Between 1978 and 1983, the Household Responsibility System was introduced, under which the decision making power over agricultural surplus was returned to individual rural households. In 1983 – for the first time since 1958, when the hukou system2 was implemented to restrict peasants’ mobility – rural residents were given permission to travel outside their villages to seek business opportunities and outlets for their products, and in 1984, farmers were allowed to work in the TVE sectors in nearby towns. TVEs helped to absorb China’s huge surplus of labor from the agricultural sector, exert competitive pressure on state-owned enterprises, generate tax revenues for localities, and expand the domestic market (Arrighi, 2007). TVEs also led to rapid industrialization and urbanization of the countryside, and no other developing country had similar success in raising productivity and living standards in rural areas. Overall, focusing on local institutional contexts, Arrighi argues that the legacies of socialism and the achievements of TVEs in the 1980s are what prepared the ground for China’s economic miracle later on.

Economist Huang Yasheng attributes China’s economic take-off to the TVE initiatives in the 1980s as well, rather than conventional mechanisms of growth such as private ownership, property rights, and financial liberalization. The TVE initiatives of the 1980s, according to Huang, encouraged private entrepreneurship and led to decentralization in the following decades (Huang, 2008). However, rather than viewing China’s growth as continuous and accelerating after the initial take-off of the rural sector, Huang notices a rupture in the Chinese growth strategy. He observes that beginning in the early 1990s, China reversed many of its highly productive rural experiments with TVEs, and China’s policymakers have since favored cities instead of rural areas for investment and allocation of resources. Shanghai – China’s largest commercial city – best illustrates this urban-biased growth model, according to Huang. During the second half of the 1980s, Shanghai’s leaders gradually came to dominate national politics by taking top positions in the central government, and since then the central government has initiated many policies favorable to economic development in Shanghai, such as establishing Pudong New District in 1992, the first district of its kind, designed to jump-start a financial center. The Shanghai city government restricted the development of small-scale, entrepreneurial, and rural businesses, and favored instead foreign companies and large enterprises with strong government connections. Contrary to the common praise and admiration for Shanghai, in Huang’s account Shanghai is one of the least entrepreneurial cities in the country. Huang argues that the Shanghai model of growth is expensive and leads to sharp social inequality. For example, relative to the national mean, Shanghai’s GDP increased massively in the 1990s, but the average household income did not change much. Also, since 2000, during a period of double-digit GDP growth, the poorest population segment in Shanghai has seen its income further decrease. In Huang’s narrative of China’s ascent, there are two Chinas – the entrepreneurial, market-driven rural China, and the state-led urban China. In the 1980s, rural China gained the upper hand, but in the 1990s, the situation was reversed and Chinese development became more urban-driven.

The two explanations introduced above – one from the perspective of neoliberalization and the other focusing on local institutional arrangements – complement one another, and together they provide a fuller account of the rise of China. It is crucial to recognize the local historical and institutional context in which the transformation from a planned to a market economy took place, but it is also important to keep in mind that China’s reform measures would not have been as effective as they were without the larger trends of neoliberal economic restructuring, which opened up space for China to integrate itself into the world economy. Moreover, as Huang Yasheng correctly observes, there was an “urban” turn in the early 1990s in state development policies, evidenced by the massive investment in urban regions, strong intervention by local governments in the micro-management of economic affairs, and tax policies favoring foreign and state-owned enterprises while discriminating against domestic, private, and rural entrepreneurship. In short, China’s economic boom since 1990 is an urban boom, and the Chinese miracle is made in its largest urban regions.

THE URBAN TRANSITION

China is the most populous country in the world, and it is no easy task to gather accurate statistics on how many people currently live in the country and how the population is geographically distributed. Beginning in 1953, the government has been conducting a population census about once every ten years – in 1953, 1964, 1982, 1990, 2000, and 2010 – except during the period of the Cultural Revolution. The most recent census, the Sixth National Population Census, was carried out in 2010 and it required more than 1 million census workers to complete.

The past six censuses have documented China’s urbanization levels – that is, the percentage of “urban population” in the national total – during the second half of the twentieth century, but demographers and geographers have long pointed out that the criteria used to define the “urban population” vary from census to cens...

Table of contents

- Cover

- China Today series

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Figures and Tables

- Map

- Chronology

- Preface

- 1 China Urbanized

- 2 Governance

- 3 Landscape

- 4 Migration

- 5 Inequality

- 6 Cultural Economy

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Urban China by Xuefei Ren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Urban Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.