- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

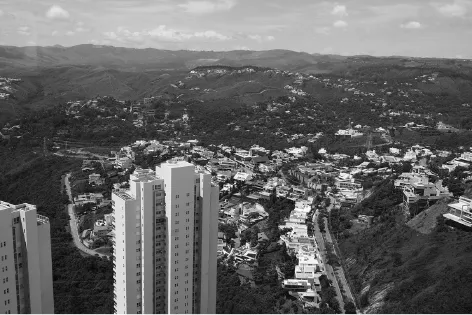

The urban century manifests itself at the peripheries. While the massive wave of present urbanization is often referred to as an 'urban revolution', most of this startling urban growth worldwide is happening at the margins of cities.

This book is about the process that creates the global urban periphery – suburbanization – and the ways of life – suburbanisms – we encounter there. Richly detailed with examples from around the world, the book argues that suburbanization is a global process and part of the extended urbanization of the planet. This includes the gated communities of elites, the squatter settlements of the poor, and many built forms and ways of life in-between. The reality of life in the urban century is suburban: most of the earth's future 10 billion inhabitants will not live in conventional cities but in suburban constellations of one kind or another.

Inspired by Henri Lefebvre's demand not to give up urban theory when the city in its classical form disappears, this book is a challenge to urban thought more generally as it invites the reader to reconsider the city from the outside in.

This book is about the process that creates the global urban periphery – suburbanization – and the ways of life – suburbanisms – we encounter there. Richly detailed with examples from around the world, the book argues that suburbanization is a global process and part of the extended urbanization of the planet. This includes the gated communities of elites, the squatter settlements of the poor, and many built forms and ways of life in-between. The reality of life in the urban century is suburban: most of the earth's future 10 billion inhabitants will not live in conventional cities but in suburban constellations of one kind or another.

Inspired by Henri Lefebvre's demand not to give up urban theory when the city in its classical form disappears, this book is a challenge to urban thought more generally as it invites the reader to reconsider the city from the outside in.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Suburban Planet by Roger Keil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Urban Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

‘[T]he tremendous concentration (of people, activities, wealth, goods, objects, instruments, means and thought) of urban reality and the immense explosion, the projection of numerous, disjunct fragments (peripheries, suburbs, vacation homes, satellite towns) into space.’

(Lefebvre 2003: 14)

When it comes to how and where we dwell, work and have fun, we live in times of rapid change. Few periods in history, barring the industrialization of Europe, the urbanization of Latin America and the suburbanization of North America, have seen as much change as the period we are currently going through. We can assume that urbanization marks the moment of our shared experience as planetary citizens. The United Nations' World Urbanization Prospects (United Nations 2014) estimates that while in 1950 a total of 746 million lived in urban environments, by 2045 more than 6 billion are expected to be urbanized. This development has been widely understood now to be shaping global development goals in what some have referred to as the Urban Age (Burdett and Sudjic 2007; 2011; Brugmann 2009). Such thinking has been subject to some serious methodological criticism as scholars have pointed out that we ought to think less of people in cities than people in urban society, less in categories such as global and megacities and more in terms like ‘planetary urbanization’ (Brenner and Schmid 2015; Gleeson 2014; Ren and Keil 2017).

While these critiques are incisive and important, the current book aims at an intervention on a different terrain. The notion of an urban age suggests in its core a move of urban populations from more dispersed into denser environments for residence, work and recreation. This move towards more compact spatial patterns for work and life is certainly borne out by the world's ‘final migration’ to move to the ‘arrival cities’ of the twenty-first century (Saunders 2011). The global migration of millions of first time urbanites in less developed countries is mirrored by a distinct move towards re-urbanization in industrialized countries that had been going through half a century of de-industrialization, suburbanization and urban decline. What is more, these processes have been welcomed and normatively prescribed by planners and urbanists responding to challenges of climate change and sustainability that are said to be met more readily in compact, denser cities. While such processes of re-urbanization, densification and compactness are real and imagined features of the urban age, this book occupies itself with questions of urban growth that are better understood if we take into account tendencies towards urban expansion, de-centralization and suburbanization. As we will explore in a sequence of historical, conceptual and thematic chapters, much of the urban age is, at closer inspection, rather a suburban age. We live on a suburban planet. This observation is supported by statistical evidence that shows, as has the work of Shlomo Angel and colleagues (Angel, Parent and Civco 2010; Angel, Parent, Civco and Blei 2010) among others, that the growth of cities' populations and activities is characterized by a disproportional expansion of those cities' territory. In other words, as the world urbanizes, cities also become less densely populated, their spaces less intensively used.

It is expected that in 2030 urbanized land on the planet will cover 1. 2 million square kilometres. That is twice as much as in 2000. Urbanization at this incredible rate must give everyone pause. This ubiquitous trend will imply significant consequences for climate change, biodiversity and so forth (Seto, Güneralp, Hutyra 2012). In the near future, another three billion humans will have to be housed.1 Most of the future inhabitants of the earth's crust will be living in entirely new cities that run the spectrum from Corbusian nightmares to ‘broadacre’ campuses and squatter camps and many more of those who already live in cities will move to those new, mostly suburban environments, too. None of them, perhaps with the exception of the odd historicizing Chinese new town, will look like nineteenth-century Manchester or Paris, or the heart of Amsterdam or Barcelona (Swilling 2016). Two aspects stand out in this perspective: first, this projected urbanization will be extremely unequal, with China and Africa absorbing the lion's share of global urbanization during the next generation; second, we can expect that the majority of the urban expansion we face in the next generation or two will not mirror the current trend towards re-urbanization, widely celebrated in the urban North, but will continue to be extensive in nature. This will take wildly different forms in places such as China or Turkey, where more dense, high-rise type suburban developments are driven by large-scale state-sponsored programmes and (most of) Africa or India, where we see continued and continuous lower density suburbanization prevail (Bloch 2015; Gururani 2013; Mabin 2013; Wu and Shen 2015; Wu 2013). At the same time, there will also be additional suburban extension of cities in North America, Europe and Australia, where half-hearted growth controls can barely withstand the tide of further sprawl – residential, commercial and industrial –, often now driven by aggressive infrastructure development, including airports, private motorized transportation and public transit that now reach the far corners of the commuter shed and extend the urban region (Addie and Keil 2015).

The notion of an urban planet is not new. Manuel Castells, for example, notes as early as 1976 that American elites were operating on the assumption that an urban world had dawned. He quotes Senator Abraham Alexander Ribicoff, who observed : ‘To say that the city is the central problem of American life is simply to know that increasingly the cities are American life; just as urban living is becoming the condition of man across the world ….’ (quoted in Castells 1976: 2–3). Ribicoff emphasizes a qualitative, rather than a mere quantitative shift towards urban life: ‘The city is not just housing and stores. It is not just education and employment, parks and theaters, banks and shops. It is a place where men should be able to live in dignity and security and harmony, where the great achievements of modern civilization and the ageless pleasures afforded by natural beauty should be available to all’ (quoted in Castells 1976: 3). Henri Lefebvre, had preceded Castells by a few years to announce the coming of an ‘urban society’. In his book La revolution urbaine, first published in English in 2003, Lefebvre predicted that society was going to be irreversibly urban as the production of urban space was becoming the central process through which capital was accumulated and the reach of the city extended far beyond its immediate physical borders through metabolic relationships that spanned the world (Lefebvre 2003).

In the half-century that has passed since these early premonitions of an urban world, many have jumped on the bandwagon of pronouncing the onset of the urban age. An entire industry of Lefebvre scholarship has sprung up to celebrate the possibilities of claiming the Right to the City in an urbanized world. Most recently, perhaps, the declaration of an epoch of ‘planetary urbanization’ has been the most influential mode of carrying Lefebvre's message forward (Brenner 2014). In this wave of urban enthusiasm for the revolutionary potential of urbanization and sharp critique of mainstream urbanism, the idea that cities both ‘explode’ and ‘implode’ as expressed in the epigraph at the top of this chapter has gained ground to describe that processes of densification ‘here’ stand in direct relationship with processes of de-centralization ‘there’. An ‘oscillating growth dynamics’ (Keil and Ronneberger 1994) has been characteristic of the waves of urbanization that have swept the world's metro areas: as the centres gain in population and economic activity, so do the peripheries. When the Frankfurt Airport at the city's edge expands, so do the activities of the financial industry in the core. As the fringe of Toronto is stretched into the fields abutting the protected Oak Ridges Moraine (Gee 2017), the condominium towers in the inner city mushroom into the sky. As Los Angeles makes one attempt after another to anchor a resident population in its gentrifying downtown (Dillon 2017), its desert frontier continues to be pushed out indefinitely despite the (subprime) crisis writings on the wall.

John Friedmann, the great American planner, has used the terms ‘prospect of cities’ and ‘the urban transition’ to point out the irreversible inevitability of the world turning urban (2002). The urban transition is the unstoppable movement from the rural and agricultural to the urban. Already in the 1960s, he saw the urban field as the spatial form of the urban transition: ‘It is no longer possible to regard the city as purely an artifact, or a political entity, or a configuration of population densities. All of these are outmoded constructs that recall a time when one could trace a sharp dividing line between town and countryside, rural and urban man. ’ (Friedmann and Miller 1965: 314). This transition is, of course, not just one of brick and mortar, infrastructures and technologies, it involves urbanization of the world's ways of life: ‘We are headed irrevocably into a century in which the world's population will become, in some fundamental sense, completely urbanized’ (2002: 2). The expansion and consolidation of global capital can be assumed to continue and the urban transition to be completed over the course of this century. Friedmann and Miller note in their once pathbreaking piece on the urban field: ‘The pattern of the urban field will elude easy perception by the eye and it will be difficult to rationalize in terms of Euclidean geometry. It will be a large complex pattern which, unlike the traditional city, will no longer be directly accessible to the senses’ (1965: 319). This expansion of urban form and urban imaginary is akin to the explosions noted by Lefebvre (2003).

In Time Magazine Bryan Walsh (2012) notes that ‘The urbanization wave can't be stopped – and it shouldn't be’ but pleads for a change in the way we build cities in the future in order to make urbanization sustainable. But how are we really building cities? It seems that over the past two hundred years, not to mention for thousands of years before, we have been mostly building cities in a manner of concentric expansion of rings around a typically religious or secular seat of power and around a market place. Many core cities have experienced ‘Haussmannization’ of one kind or another throughout the twentieth century, with added axes, corridors and central intensification and structuration. Others have been altogether invented as products of a modern age, as have Brasilia or the bombed out European cities after the Second World War. But most of modern urbanization has been an ongoing process of suburban extension. Over time, those suburbs became cities themselves. They tended to become denser, less informal, more reliant on technologies of mobility. In pre-industrial times, the extension was minimal. Much of it had to do with limited technologies of mobility. Militarily the city's compact form was also an advantage as it could be defended better. In the industrial and automobile city of the twentieth century, the extension is celebrated not just as a temporary state that would soon be giving way to a more traditional form of urbanism. On the contrary, the extension was now considered a legitimate, if not preferred form of urbanism: in the periphery, more than in the centre, the true expression of society's success was to be found, whether that was the single-family home subdivision of the American dream, the new towns of the Soviet empire or the housing estates of social democratic Europe and Canada. That there would be a way back to the core from the garden cities, satellite towns and subdivisions of the automobile metropolis would have sounded implausible or even undesirable to mid-century planners and city builders. Yet, for the most part, those consecutive waves of twentieth century suburbanization were still dependent on and related to the urban centre, whether it was for financing of infrastructure, jobs or government services. Towards the end of the millennium, though, this changed. Often discussed in the context of the Los Angeles School of urban studies, we are beginning to see the dissolution of centrality as we knew it. Instead, the urban form becomes polycentric and the suburbs themselves appear more as free-floating units (Soja 1996; 2000).

The argument I am putting forward in this book is that under the conditions of current trends in technology, capital accumulation, land development and urban governance, the expected global urbanization will necessarily be largely suburbanization. Yet, we (as in urban professionals, planners, scholars of urban studies, etc.) have collectively embraced centralism and compactness as the guiding idea of twenty-first-century urbanism, just at a time when there is a massive explosion in the way land around existing cities is used. Suburban land, as one of the chief products of post-neoliberal capitalism, continues to be readied for settlement whether it is in the form of subdivisions in North America or squatter settlements in India or Africa. Around the globe, suburbanization now occurs without the automatic assumption that this may lead to denser, more central forms of urbanization later – although it may.

Following Andy...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Urban Futures Series

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Suburbanization Explained

- 3: Suburban Theory

- 4: Suburban Studies

- 5: From Lakewood to Ferguson

- 6: Beyond the Picket Fence: Global Suburbia

- 7: Suburban Infrastructures

- 8: The Urban Political Ecology of Suburbanization

- 9: The Political Suburb

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement