- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

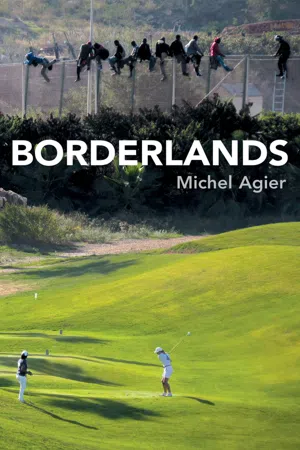

The images of migrants and refugees arriving in precarious boats on the shores of southern Europe, and of the makeshift camps that have sprung up in Lesbos, Lampedusa, Calais and elsewhere, have become familiar sights on television screens around the world. But what do we know about the border places – these liminal zones between countries and continents – that have become the focus of so much attention and anxiety today, and what do we know about the individuals who occupy these places?

In this timely book, anthropologist Michel Agier addresses these questions and examines the character of the borderlands that emerge on the margins of nation-states. Drawing on his ethnographic fieldwork, he shows that borders, far from disappearing, have acquired a new kind of centrality in our societies, becoming reference points for the growing numbers of people who do not find a place in the countries they wish to reach. They have become the site for a new kind of subject, the border dweller, who is both ?inside? and ?outside?, enclosed on the one hand and excluded on the other, and who is obliged to learn, under harsh conditions, the ways of the world and of other people. In this respect, the lives of migrants, even in the uncertainties or dangers of the borderlands, tell us something about the condition in which everyone is increasingly living today, a ?cosmopolitan condition? in which the experience of the unfamiliar is more common and the relation between self and other is in constant renewal.

In this timely book, anthropologist Michel Agier addresses these questions and examines the character of the borderlands that emerge on the margins of nation-states. Drawing on his ethnographic fieldwork, he shows that borders, far from disappearing, have acquired a new kind of centrality in our societies, becoming reference points for the growing numbers of people who do not find a place in the countries they wish to reach. They have become the site for a new kind of subject, the border dweller, who is both ?inside? and ?outside?, enclosed on the one hand and excluded on the other, and who is obliged to learn, under harsh conditions, the ways of the world and of other people. In this respect, the lives of migrants, even in the uncertainties or dangers of the borderlands, tell us something about the condition in which everyone is increasingly living today, a ?cosmopolitan condition? in which the experience of the unfamiliar is more common and the relation between self and other is in constant renewal.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Borderlands by Michel Agier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Decentring the World

1

THE ELEMENTARY FORMS OF THE BORDER

‘“Customs officers without borders” is something for tomorrow’, Régis Debray wrote in his Éloge de la frontière.1 ‘You have a Frenchman here, I admit’, he continued in this lecture given in March 2011 at the Maison Franco-Japonaise in Tokyo, as if to mark from the start an opposition between identity and border. Then, mentioning natural and political borders, more or less vulnerable, he went on to insularity and its specific effects (homogeneous Japan being different in this respect from Cyprus and Ireland, divided by their ‘internal’ national borders), and finally denounced the political consequences of ‘sans-frontiérisme’. Régis Debray was seeking to relaunch public debate on the subject of borders, as if the scales had swung too far in one direction, that of a global village without borders; as if, in return, a frightful illusion was born from this collective belief in a world that had already come to form a limitless whole, open to the void; and as if, finally, this fear explained the construction of immense walls and new barriers with the object of identity protection.

It is certainly true that arguments are not lacking for a wholesale process of what Debrary calls ‘illimitations’ and an ‘oil-and-vinegar globalization’.2 But by seeking too hard to convince at the level of theory, Debray ends up falling into the trap of seeking out and seeking to preserve the ‘truth’, the ‘heart’ and ‘matrix’ of identity; insisting too much on the opposition between inside and outside, he forgets that the world of today is largely made up, whatever he may say, of mobilities either free or compelled, of absences of ‘home’ and of anchorages that are ever more uncertain. If we want something other than a conservative and identity-based resistance, we should indeed set out to rethink the meaning of borders in the world, to ask how they may still be ‘good for thinking’ and ‘good for living’.3

The border as centre of reflection

What we shall offer here, therefore, is not a ‘praise’ but rather a more analytical attempt to understand the double state of the border question, which will perhaps give more weight and argument to humanist positions while at the same time posing some other basic problems for these.

An initial formulation of the question concerns the social and non-natural foundations of the border, understood as a condition of being-in-the-world and reciprocal recognition of self and others. A second confronts these principles with contemporary reality, in which the enthusiasm of some people for the abolition of borders is followed by a praise of borders on the part of others sharing the same humanist sensibility. This duality is caricatured in a paradoxical representation of globalization: one of flows that cross borders and walls that seal them. Pushed to the extreme, this paradox involves a theoretical impasse that causes borders to disappear in one of two ways: by replacing them with walls or by ignoring their existence. It is important to shed light on the concepts with which we claim to describe and understand the world that surrounds us. Words are important: in the course of this book I shall establish a distinction between the notion of ‘identity’ and that of ‘subject’, a distinction that will allow me to present and test the idea according to which the person who seems ‘foreign’ to me is the ‘other’ subject that my identity needs in order to exist and endure. I shall thus place the border at the centre of my reflection.

The geographer Michel Foucher, an acknowledged expert on borders, offered in 2007 a geopolitical survey in which he described ‘the global stage of borders … marked by a double movement of obsolescence and resistance on the part of its attributes’.4 On a basis of wide and precise documentation, he examined the regional and national histories of borders. Each of these is the result and sometimes still the object of political negotiation, war, separation or conquest, while from one generation to another the issues at stake in border lines tend to change or even disappear (as in the case of walls and partitions in Cyprus or Ireland, where the question of two nations has become obsolete for the children and grandchildren of combatants). Orienting his analysis to the political borders of states, Foucher describes their central role in the legitimation of nation-states that have only recently gained independence (as with the former Soviet republics), or their transformation in the long negotiation of the external and internal boundaries of a regional framework (the moment that Europe has been undergoing since the 1980s). This geopolitical and strategic inventory is remarkably well documented and up to date.5 However, in order to grasp the human (and not just political) dimension of the border, it is necessary to expand considerably the sample of places and moments taken into account, beyond the boundaries of nation-states alone – to what I shall call border situations.

Moreover, I believe it necessary to signal two basic disagreements right away, as these will enable me to spell out what an anthropology of borders may mean. On the one hand, the geostrategic approach views walls as simply an instance of borders, depriving them of their radical meaning, that of a physical and symbolic violence, and thus tending to ‘banalize’ their existence in the name of political realism and the lesser evil. On the contrary, as we shall see, the wall is the negation of the border, even if this requires freeing ourselves for a moment from political actuality. It crushes borders, making them disappear, until the ‘walled’ (who include, of course, those walled out) overthrow it or transform it and make it disappear by cutting holes in it, putting up ladders or equipping it with gates.

On the other hand, Michel Foucher’s approach (which is also found more widely among the champions of realpolitik) consists in taking as given and beyond dispute the reference to ‘identitarian projects’, national or ethnic identities as the first cause that determines the course, legitimacy, and greater or lesser openness or closure of borders. However, it is precisely the two-fold conflict between ‘identitarian’ and relationship, between wall and border (the wall being to the border what identity obsession is to relationship), that in my view has to be deciphered and overcome. This will make it possible to challenge the false identity-based obviousness on which arguments of global or national ‘governance’ are based, particularly what is today known as ‘political realism’. For, if we want to be precise, the contemporary fury with which walls are constructed is the expression less of what Michel Foucher calls an ‘obsession with borders’ than of an obsession with identity. And its spread is the sign of a very current propensity, which Wendy Brown has called, in a rather provocative fashion, a ‘desire for walls’,6 and what I shall analyse as an identity trap.

Why not slow down and note that we are still in the final episodes of what Marc Augé has called the ‘prehistory of the world’,7 slow down and recognize the complexity of the challenge, at whatever place on Earth we happen to be, to simultaneously think globally and act effectively where we are, locally? The object of anthropology is not to praise borders – accrediting the idea that walls are simply an instance of these – unfortunate for some, inevitable for others. Nor is it to produce ‘manifestos’, whether favourable to them or unfavourable, nor again to advise defenders of world ‘governance’, but rather to challenge the false obviousness of borders, world, and the global scale of power and politics. Above all, anthropology can contribute to understanding why and how humans constantly invent new borders in order to ‘place’ themselves in the world and vis-à-vis others, how they did so in the past and are continuing to do so today.

Temporal, social and spatial dimensions of the border ritual

This will be the first point in my argument: the border ritual attests to the institution of all social life in a given environment; it determines the division from and relationship with the natural and social world that surrounds it. Before describing the moment of crossing at the wall, therefore, we have to go back to the principle of the border. For this purpose, rather than regarding the border as a fixed and absolute fait accompli (let alone the wall as just one of its possible instances), it is necessary to study the border as it is being made. What the border displays is both a division and a relationship. Its action is double, external and internal; it is both a threshold and an act of institution: to institute one’s own place, whether social or sacred, involves separating this from an environment – nature, city or society – which makes it possible to inscribe a given collective, a ‘group’ or ‘community’ of humans in the social world with which, thanks to the border created, a relationship to others can be established and thus exist.

This separation/relationship is the object of an act of foundation and delimitation, it relates to an event out of the ordinary, which needs to be repeated according to ritual rules or a ritual calendar of commemoration or renewal of the boundary. Closely linked to this historic event that instituted it within the world that surrounds it, the border permits recognition of a group in the social world, and the inscription of a place in space. It is this being inscribed in three relative dimensions that it is important to keep in mind, and whose place we shall have to verify case by case: time, social world and space.

It is temporal in the sense that the place and the community have not always existed; they were founded at a given moment, and this relativity of every border between a before and an after also leads us to suppose that the event might well not have taken place: it is thus symbolically effective to recall the event and the division in time that it has realized.

The border is also social in the sense that the threshold where the instituted group symbolically begins is recognized on both sides, which also means that the placing in relationship – and beyond this, the relational framework represented by the border itself – are necessary for the double recognition of self and other.

Finally, the border is spatial, the boundary has a form that partitions space and materializes an inside and an outside. Even when the social separation is not materialized by a border in space, this is never just a metaphor. For example, if we speak, as Fredrik Barth has done,8 and after him several other ethnologists, of the boundaries of ethnic groups, these are certainly symbolic ones – basically meaning that everyone knows what they can and should do or say, or cannot and should not, in this or that context – but it is rare indeed for these boundaries not to find expression, at least provisionally, in a space of contact and exchange that makes a border.

It follows from what has been said that on all these levels, spatial, social and sacred (and here we consider the sacred as one production of the social), a constant characteristic of the border is its intrinsic duality – a point we shall return to; it is itself constituted by two sides or two edges, like a line drawn in pencil whose thickness can be seen only under the microscope. Anthropology of the border must then become anthropology in the border.

Community and locality: the border...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface to the English Edition

- Introduction: The Migrant, the Border and the World

- Part I Decentring the World

- Part II The Decentred Subject

- Index