- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment in Schools

About this book

Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment in Schools serves as a guide on how to assess children for autism spectrum disorders (ASD), specifically in school settings. Dilly and Hall offer a general overview of ASD, describe ASD assessment best practices, and explain the process of identifying ASD in schools. Current research and up-to-date science is incorporated in a practitioner-friendly manner, and short case vignettes will increase the accessibility of the book content and illustrate principles. As the rates of ASD reach 1/59 children, and school psychologists are increasingly expected to possess expertise in the assessment of ASD, this book serves as a must have for school psychologists, school social workers, and other practitioners.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment in Schools by Laura Dilly,Christine Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Counseling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Chapter 1

History and Core Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorders

As the rates of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have increased to 1 in 59 children in the USA, the public schools have faced an increasing charge to educate children with ASD (Baio et al., 2018). With this increase, school psychologists, speech and language pathologists, social workers, and special educators are expected to possess a high level of expertise and skill to accurately identify children with ASD and assist their families. School professionals experience unique demands in conducting ASD assessments within the context of the school culture. The school culture includes unique purposes, language, norms, regulations, and history which are distinct from other environments. Within schools, some of the contextual complexities of conducting ASD assessments involve the need to conduct assessments in order to determine eligibility for special education, the complex relationships between schools and parents of children with ASD, and state and federal legislation. Although guidelines abound for clinicians working within medical settings, conducting ASD assessments in public schools involves additional complexities and requires thoughtful adaptations and extensions of best practices.

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Social Communication

The primary characteristic of ASD is a difference in a child’s social communication and interactions. Typically developing children are hard-wired to seek social input. From the first weeks of life, human voices and faces are the most interesting stimuli in the environment. These interactions are rewarding and therefore reinforced. A baby coos toward her mother, a mother smiles back, and a baby receives positive feedback, increasing directed coos. However, children with ASD show a different developmental trajectory. Although typically developing children show a natural proclivity to learn from the social world, children with ASD tend to be more drawn to interacting with the physical world (Klin et al., 2002). Typically developing children show increasingly more skill in interacting with others, interpreting the social intent of others, and engaging in shared enjoyment with others.

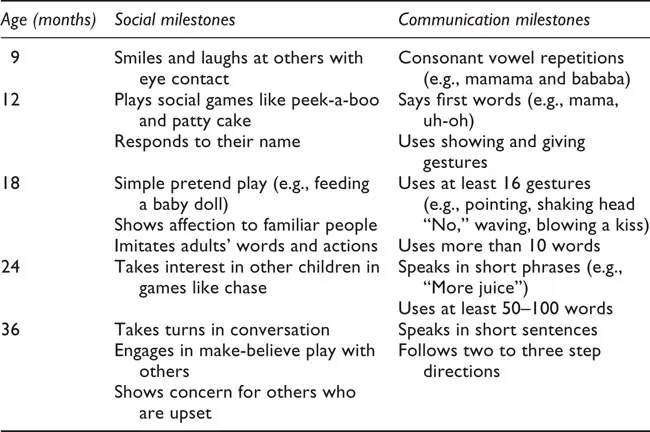

Early symptoms of ASD are related to children’s social communication. Although language and motor milestones of children are often monitored, milestones also exist for typical children’s social communication and interactions. The use of gestures and social skills are included in this domain. Typically developing children use gestures to nonverbally communicate and interact. Related to gesture use, by the age of 16 months, typically developing children exhibit around 16 gestures (First Words Project, 2017). As infants and toddlers develop, they begin to use gestures not only to obtain objects they want (e.g., reach, point) or in conventional ways (e.g., waving, blowing a kiss), but then also to describe actions (e.g., using a finger through the air to describe a spaceship taking off, pretending to put their hand on a steering wheel to drive). Socially, typically developing children begin their development during the early weeks, responding to their mothers’ voices, orienting to faces during the first weeks of life, and socially returning a mother’s smile (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980; Haith, Bergman, & Moore, 1977; Kaye & Fogel, 1980). These are some of the early social communication and interaction skills that children with ASD may miss or delay developing. They are often the red flags that a child may have an ASD.

Table 1.1 Early social and communication milestones

Table 1.2 Resources on typical development and developmental differences

Learn the Signs. Act Early (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/index.html): The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s free developmental milestone tracking app, growth charts, and books.

First Words Project (http://firstwordsproject.com/): Online lookbooks and growth charts related to children’s development in the areas of language, gestures, imagination, social connectedness, cooperation, and critical thinking that is supported by research at Florida State University.

Autism Navigator (http://www.autismnavigator.com/): Collection of online resources and videos for professionals and families to explore autism that was created by the Autism Institute at the Florida State University College of Medicine.

As children with ASD progress through school, social communication and interactions continue to lag. They can struggle more with forming friendships as well as knowing how to initiate and respond to interactions with their peers appropriately. Pragmatic aspects of language such as the back and forth of conversations of interest to others and use of appropriate body language may be challenging for children with ASD. Figurative language and idioms may be also difficult to understand. Children and youth on the spectrum may also struggle in understanding and expressing emotions.

Repetitive, Restricted Patterns of Behavior and Interests

In addition to differences in social communication and interests, children with ASD also exhibit patterns of repetitive, restrictive behaviors and/or interests. One pattern of repetitive behavior that children may demonstrate is stereotypic behaviors such as hand flapping, jumping, tensing and shaking, and spinning. In addition, their language may contain echoes of statements made by others or heard in their favorite videos. They may also like spinning or lining up objects. Second, children with ASD may by highly dependent on routines or patterns of behavior. They may become very upset when a change in routine is made or have difficulty transitioning between activities in the classroom. Transitioning in from recess, going on a field trip, or having an assembly is often a trigger for problem behavior. Their thinking can be very rigid. For example, they may be described as thinking in black and white or being very particular about the use of words and language. Third, children with ASD may have an excessively strong interest in an object or topic. For example, a child may be overly focused on blue straws, trains, princesses, garbage, the Civil War, or Justin Bieber. Finally, children with ASD may demonstrate differences in how they respond to sensory input. Children may seek out visual input from lights and mirrors, sounds by putting their ear to the radio, smells by smelling objects that are not food, or touch by rubbing objects to their hand or face. In contrast, some children with ASD show adverse reactions to sensory input like loud sounds such as fire alarms, crowded events like baseball games, touch from clothing or shoes, and textures of specific foods. Sometimes they are also described as having a high pain tolerance.

Case Study 1

Alexa is a 4-year-old girl whose pediatrician had her parents call the school district to inquire about possible special needs preschool. Alexa was speaking a few words at age 18 months such as “juice,” “dog,” “mama,” and “shoe.” She then stopped saying these words and became more withdrawn. Now, in order to access things she wants, Alexa will use some occasional phrases to communicate such as “More milk” and “Go outside.” While she does not point to what she wants, she will reach toward objects, go and get them to give to her mother, or put her mother’s hand on them. When around other children, Alexa often keeps to herself. She tends to be very focused on objects. In particular, Alexa likes to carry beads with her and rub them across her top lip. She will also shake them in front of her eyes for prolonged periods. Alexa’s mother states that she stomps her feet and moves her hands when she gets excited. They call it the “Alexa dance.”

What social communication and interactions deficits are possibly present?

What repetitive and restricted patterns of behavior and interests are present?

What additional history regarding the possible presence of ASD symptoms would you like to gather?

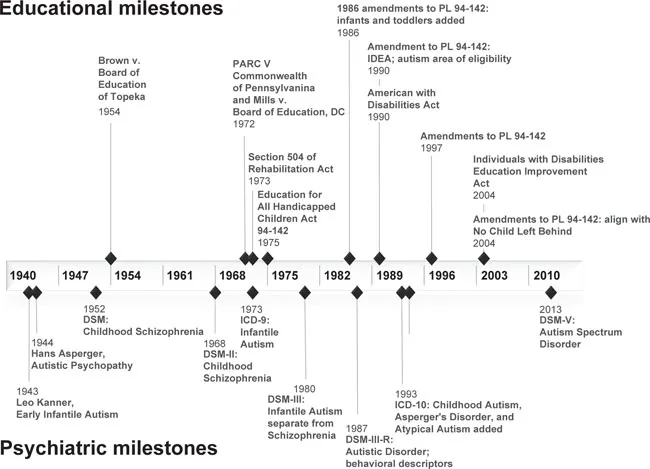

Brief History of Autism Spectrum Disorders

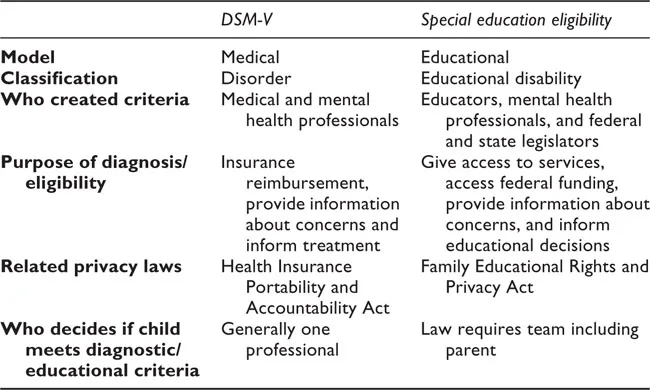

Although descriptions of individuals with symptoms consistent with ASD in the literature have long been noted, it has not been until fairly recent decades that the medical and education communities have officially recognized ASD. Over the last 100 years, the medical system has gradually refined its diagnostic description of ASD and the educational system has gradually outlined ASD through special education law (Table 1.3). The purposes of these two systems vary as do their related laws and funding sources (Figure 1.1).

Table 1.3 Differences between the medical and educational systems

Psychiatric and Medical History

The first descriptions of ASD were developed by psychiatrists in order to describe a cluster of symptoms in their patients. In 1911, Eugen Bleuler first used the German term autismus (Bleuler, 1950). The term is derived from the Greek words autos, meaning self, and ismos, a suffix referring to action or state. Bleuler described autismus as a form of schizophrenia that was particularly severe, in which individuals lived in a world of their own and were detached from reality.

In 1938–43 in Austria, Hans Asperger began to describe symptoms of autistic psychopathy while he was a medical student in Vienna (Czech, 2018). He wrote about a group of boys who struggled to form social relationships, but had some strong language and communication skills (Asperger, 1991). They tended to be “little professors” and often had a strong interest in a highly specific topic. He viewed the condition as more of a personality trait than a developmental disability and used the term “autistic psychopathy” or “autistic personality disorder.” Notably, in the past, Asperger was seen as a protector for individuals with disabilities during the World War II era. However, recent historical research has reconsidered the idea that Asperger was an opponent of Nazi race-hygiene measures. Instead, Asperger likely cooperated with the National Socialism policies related to “euthanasia” for a small number of patients who were considered “uneducable” (Czech, 2018).

Figure 1.1 Educational and psychiatric ASD milestones

Around the same time, in 1943 in the USA, Leo Kanner described 11 of his patients as having early infantile autism (Kanner, 1943). They demonstrated what he called “an inborn disturbance of affective contact” such that they showed characteristics of withdrawn behavior, problems with change, repetitive behaviors, and echoing of language. He noted that these symptoms had been present since birth, rather than something that developed over time as in schizophrenia; therefore, he described something that resembled a developmental disability. The children he saw were more interested in the world of objects, rather than the social world of people.

More recently, it has been discovered that a third man, George Frankl, may help explain how ASD could be simultaneously described in Austria by Asperger and the USA by Kanner (Robison, 2017). Frankl had been a mentor to Asperger in Austria. He left Austria in 1937 for Johns Hopkins in Maryland, meeting up with his wife as well as fleeing the Nazi. He then worked with Kanner.

The first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) included descriptions of what is now recognized as ASD under the diagnosis of Childhood Schizophrenia (APA, 1952). This continued until the third edition of the DSM created the diagnosis of Infantile Autism, separating it from Schizophrenia (APA, 1980). The DSM-III-R created the diagnosis of Autistic Disorder and provided the first behavioral descriptions of autism (APA, 1987).

Then, in 1994, the DSM-IV added diagnoses of Asperger’s Syndrome and Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified (APA, 1994). Most recently, in the DSM-V, all forms of ASD have been collapsed into the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (APA, 2013). According to the DSM-V, individuals with ASD must show (1) persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, and (2) restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These symptoms have to have been present since early childhood and must currently affect social, occupational, or other areas of functioning. Specifiers related to the level of support that an individual needs in the areas of social communication/interactions and restricted, repetitive behaviors and interests can also be added.

The International Classification of Diseases is the classification system that is most broadly, internationally used in medical settings. Within this classification system, the ICD-9 first identified A...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Part II Specific ASD Assessment Practices

- Part III ASD Identification in Schools

- Index