eBook - ePub

Women in Twentieth-Century Britain

Social, Cultural and Political Change

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Women's lives have changed dramatically over the course of the twentieth century: reduced fertility and the removal of formal barriers to their participation in education, work and public life are just some examples. At the same time, women are under-represented in many areas, are paid significantly less than men, continue to experience domestic violence and to bear the larger part of the burden in the domestic division of labour. Women in 2000 may have many more choices and opportunities than they had a hundred years ago, but genuine equality between men and women remains elusive. This unique, illustrated history discusses a wide range of topics organised into four parts: the life course - the experience of girlhood, marriage and the ageing process; the nature of women's work, both paid and unpaid; consumption, culture and transgression; and citizenship and the state.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women in Twentieth-Century Britain by Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Introduction

Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska

During the twentieth century women in Britain gained control of their fertility, acquired equal access to education and, in principle, the labour market, and established their status as equal citizens. Although women widened their opportunities in many areas, traditional gender stereotypes which assumed that women's primary role is in the domestic setting continued to be influential, men held on to their dominant position in society and the double standard in sexual morality proved remarkably persistent. The history of women in the twentieth century is distinguished by this interplay of change and continuity. Ultimately, it is a question of perspective whether to stress optimism by highlighting the obvious achievements of women and advances across the century or to focus, more pessimistically, on continuing discrimination and the lack of real equality between the sexes.

Women in Twentieth-Century Britain explores transformations in the position of women during last century exemplified by changes such as the reduction in fertility or the removal of formal barriers to women's participation in education, work and public life. At the same time, the limits of formal equality are demonstrated by an examination of several indicators, including the fact that women continued to be under-represented in many areas, paid significantly less then men or subject to domestic violence and sexual exploitation. Women in 2000 have many more choices and opportunities than women in 1900 but genuine equality between men and women remains elusive. These issues are discussed from a thematic perspective. In each of the four parts of the book – The Life Course, Work – Paid and Unpaid; Consumption, Culture and Transgression, and The State and Citizenship – a number of chapters explore a particular topic throughout the century up to and including the 1990s. The three chapters dealing with the women's movement are the only exceptions, since this topic required more detailed consideration. The four parts, and the chapters within them, are linked in a variety of ways; together they provide a multifaceted picture of women's history.

This book highlights differences between women which were just as important as similarities or common experiences. Women in twentieth-century Britain were not a unified category and not all women had the same opportunities, aspirations or experiences. To give just a few examples, middle-class women above all benefited from improved female access to higher education whereas only a minority of working-class women attended universities during the late 1990s. Women's opportunities were also shaped by 'race' and ethnicity. Fulltime motherhood and domesticity during the middle decades of the century was a privilege of white women whereas recent female migrants, whether European Voluntary Workers after the Second World War or West Indian and South Asian immigrants in the 1950s and 1960s, were perceived above all as workers. The experiences of young girls, on the one hand, and older women, on the other, were distinctive. The twentieth century could be seen as a period of increasing status for girls, but older women were disproportionately among the poorest members of society in 1900 and in 2000. Different generations of women had divergent aspirations and styles. The demands of feminists in the interwar years and early postwar period were relatively moderate, in contrast to both preceding and succeeding generations. Aggressive tactics were adopted by the militant suffragettes before the First World War or the activists of the Women's Liberation Movement during the 1970s. Finally, while women born around the beginning of the century had few children, those born in the interwar years again chose larger families, but their daughters, coming of age during the 1970s and later, again opted for small families.

There has been a growing interest in the history of women since the 1970s and the beginning of the new century is an appropriate opportunity to take stock and look at the history of women throughout the previous 100 years. This is important not only for women interested in tracing their own history and that of their mothers and grandmothers, but necessary in order to comprehend twentieth-century British history as a whole. As gender historians have made clear in the 1980s and 1990s, women's history is not just a sectional interest confined to ghetto status. Rather, an appreciation of women's distinctive needs and experiences is critical to understanding many social and welfare reforms during the century which were at least in part the outcome of campaigning by women's groups. Examples include the introduction of family allowances paid directly to mothers, improved maternity services, abortion rights or free access to contraception. Women made a vital contribution to the war effort during both world wars, whether in the forces, as workers in war industries, or as housewives who were responsible for maintaining civilian health and morale. Women are central to any analysis of twentieth-century demographic patterns, such as the decline in fertility or the rise in divorce, and changes in the nature of the labour market, such as the transformation of participation rates. As we move into the twenty-first century women exert an increasingly powerful influence on the pace and direction of economic, social and cultural change.

Recently women's history has been described as outmoded as gender history has taken its place, a historiographical debate which is explored in chapter 2. Gender history differs from women's history in that it focuses notjust on women, but on the relationship between women and men and, above all, on how female

Plate 1:1. Girls, c. 1900.

Plate 1.2. Girls. 2000.

and male identities are constructed. Arguably, the conflict between these perspectives can be resolved since a gendered approach has not necessarily supplanted women's history. Instead it has enriched women's history methodologically by drawing attention to the fluidity of gender identities and their relational characteristics. Moreover, the emphasis on gender differences and the distinctive roles and contributions of women has contributed to a growing recognition that history in general, and twentieth-century British history in particular, cannot make sense without taking women into account.

Women's Lives: 1900 vs. 2000

If we take a look at women's lives at the beginning of the twentieth century and compare this to a snapshot at the end of the century, there is little doubt about the extensive changes that have taken place. However, these changes have coincided with important areas of continuity. Frequently, dramatic changes only took off from the 1970s or even 1980s, following a period of relative stagnation for much of the century. This is true with regard to women's share of university places or women's participation rate in the labour force. Similarly, important demographic trends such as the rise in divorce, increase in cohabitation and the growing proportion of children born to unmarried women accelerated rapidly from the 1980s.

A girl born at the end of the nineteenth century could expect to live, on average, about 50 years whereas projected live expectancy at birth in 2000 is about 80 years for women – an increase of three decades in the space of three generations. A woman born in 1870 typically had between five and six children, of whom almost one-sixth died in infancy, whereas women born in 1970, on average, had approximately 1.7 children and by 1998 infant mortality stood at less than six per thousand.1 In 1900 there were no female MPs and women were excluded from the parliamentary franchise, although about one million female ratepayers, many of whom were widows, could vote and stand for office in local elections. At the end of the twentieth century, women could vote on equal terms with men, although women remained a minority among MPs despite the massive influx of female MPs following Labour's election victory of 1997. In the late nineteenth century, girls' education was orientated towards domesticity, a small minority attended secondary schools and higher education was only just becoming available to women who had been barred from access to universities until the 1870s. In the late 1990s the overwhelming majority of girls remained in school beyond the leaving age of 16 years, girls outperformed boys at all levels from primary school tests to A level, and women accounted for a majority of undergraduates.

These educational advances were not translated fully into equal performance in the labour market in which men remained dominant and better paid. In 1900 female workers were crowded into a narrow range of occupations, above all domestic service, textiles and the clothing industries. Most were young and single whereas married women typically stayed at home – despite important exceptions such as women workers in the Lancashire cotton industry and extensive casual earnings among working-class women. Only about a third of women were in full-time employment and, lacking in skill and experience, they typically earned about half of male earnings. At the end of the twentieth century, marriage ceased to be an important factor in women's participation rate, and almost three-quarters of women were in the labour force, although frequently on a part-time basis. While many women were employed in professional and managerial occupations, clerical, secretarial and service-based jobs were the most popular and women earned, on average, about four-fifths of the male rate.

Given women's limited educational opportunities, narrow range of occupations and low wages at the beginning of the twentieth century, it is not surprising that Cicely Hamilton described Marriage as a Trade (indeed, the only trade open to women) in which 'she exchanged . . . possession of her person for the means of existence'.2 Conventionally, marriage was portrayed as women's true destiny and the only respectable path to motherhood, although about one in six women never married. Spinsters were not only marginalised socially but economically vulnerable given the discrimination against women in the labour market. Divorce was costly and extremely rare and marriages were typically only terminated through death, although separation and cohabitation were not unusual among the working class according to the Royal Commission on Divorce of 1912. The final decades of the twentieth century witnessed what can be described as a demographic revolution, and in the 1990s between one-third and half of all marriages ended in divorce, re-marriage was common, cohabitation had become a precursor – or an alternative – to marriage and a growing proportion, one in six, lived alone. Almost 40 per cent of children were born outside marriage, in many cases to cohabiting parents. Nearly a quarter of all families with dependent children were headed by single parents, and more than nine out of ten by single mothers.

In 1900 Victorian sexual attitudes characterised by female chastity, ignorance and the construction of female sexuality as necessarily passive and responsive to male stimulation were well-entrenched. At the end of the twentieth century information about sex was generally available, female sexuality was more assertive, premarital sex was commonplace and generally condoned, and the rights of lesbian and gay couples were increasingly recognised. Nevertheless, despite this trend towards greater equality and liberalisation, in many important ways, sexual attitudes have remained remarkably persistent. Most notably, this is the case with regard to the double standard in sexual morality which condoned or even applauded male sexual promiscuity while condemning it among women. This double standard was not only morally unacceptable but also a danger to women's health. At the beginning of the century Christabel Pankhurst in The Great Scourge called for 'Votes for Women and Chastity for Men' because men who frequented prostitutes were infecting their wives with venereal diseases.3

Attitudes towards prostitution and the treatment of prostitutes by the state have shown a great degree of continuity – prostitutes continued to be blamed for prostitution, arrested, prosecuted and convicted while their male clients were generally able to use their services without impediment. The so-called sexual revolution of the final decades of the twentieth century has not resulted in a demise in prostitution and the sex industry which continued to flourish in the late 1990s. Likewise, with regard to crime, differences between male and female patterns of criminal behaviour or as victims of crime remained largely unchanged throughout the century. The overwhelming majority of offences were committed by men at the beginning as well as the end of the century, while women were more commonly victims of crime and sexual violence.

A central aspect of continuity was women's association with caring and unpaid domestic labour. In the early twentieth century, married women and mothers typically performed all the housework and caring duties – although middle-class women could rely on domestic service while many working-class wives and mothers had to take on casual employment to make ends meet. At the end of the century, women still performed the overwhelming majority of housework and most had to cope with a double burden. While women in the 1990s combined domestic responsibilities with paid employment there has not been a commensurate rise in men's share of domestic labour or childcare. Women have not been able to participate in a range of leisure activities, including most sports, on an equal level with men, largely because of lack of money at the beginning of the century and lack of time at the end. A final example of continuity is the enduring emphasis on physical attractiveness in representations of femininity which has stimulated the growth of body management as a central aspect of twentieth-century mass consumer culture. The following sections discuss women's control of their own fertility and the erosion of the separate spheres ideology.

Women Gain Control of Fertility

Arguably, the most fundamental change in women's lives during the twentieth century was the decline in fertility, especially when coupled with the increase in life expectancy. This transformation was summed up evocatively by Richard Titmuss in the 1950s:

The typical working-class mother of the 1890s, married in her teens or early twenties and experiencing ten pregnancies, spent about fifteen years in a state of pregnancy and in nursing a child for the first year of its life. She was tied, for this period of time, to the wheel of childbearing. Today, for the typical mother, the time so spent would be about four years. A reduction of such magnitude in only two generations in the time devoted to childbearing represents nothing less than a revolutionary enlargement of freedom for women brought about by the power to control their own fertility.4

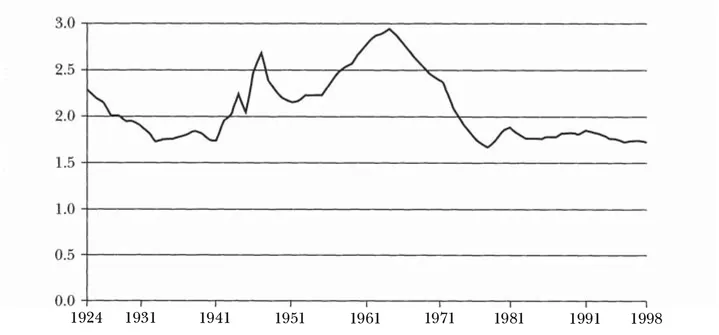

Figure 1.1. Total period fertility rate, England and Wales, 1924–98. Note: The figure refers to the number of children per woman, that is, the average number of children who would be born per woman if women experienced the age-specific fertility rates of the reference years throughout their child-bearing lifespan.

Source: Social Trends 30 (London: HMSO, 2000), p. 17.

As Figure 1.1 shows, the decline in fertility was not a simple downward trend. Rather fertility fluctuated, although it remained below the replacement rate of 2.2 children per woman for much of the century. Fertility declined until the 1930s, rose briefly during the 1940s, and increased again from the mid-1950s until the mid-1960s. Subsequently there was a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Changing the Subject: Women's History and Historiography 1900–2000

- Part One: The Life Course

- Part Two: Work – Paid and Unpaid

- Part Three: Culture, Consumption and Transgression

- Part Four: The State and Citizenship

- Key Dates and Events

- Note on Contributors

- Index