![]()

Part I Environmental Resources

![]()

Chapter 1

Nutrients

Growing Systems and Zero Waste Future

◀ Figure 1.1

Red wigglers, an essential component for vermicomposting

Abstract

Most cities maintain waste streams that do not sufficiently return nutrients to the natural cycle. Simultaneously, many ecosystems are threatened by pollution through agricultural runoff and over-fertilization. Urban agriculture offers a more holistic approach to nutrient resource management in cities, based on closed-loop systems that follow the principles of natural nutrient cycles, which are the basis for all life on Earth. This chapter provides the knowledge necessary to reestablish these recirculating systems by aligning the nutrient needs of plants with efficient growing systems and recycling strategies, such as composting, anaerobic digestion, and alternative waste management. It also illustrates their potential for integration in building systems and their beneficial impact on building performance. Chapter 1 concludes with two catalogs that provide an overview of soil-based and hydroponic growing systems and their application to urban farming.

Closing the Nutrient Cycle

The natural nutrient cycle provides a closed-loop system in which nutrients are recirculated and made available for each new growing cycle. Mineral nutrients move through the food chain from autotrophic plants—the primary producers, which transform inorganic substances under the presence of sunlight into their food—to herbivores and carnivores, then to decomposers, and back into a nutrient pool in the soil to be absorbed again by plants. This process is the basis for ecological recycling. Human interventions and industrialization, however, have disturbed this natural cycle.

Though the effects of human activity on the carbon cycle, such as global warming, are widely recognized and publicized, human impacts on the nutrient cycle remain less acknowledged. This lesser-known cycle is composed of the two great biogeochemical cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus.1 As with the carbon cycle, the injection of vast quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus into the environment through chemical fertilizers has dramatically increased agricultural outputs and short-term prosperity without developing the closed-loop systems that support perpetual soil fertility. Furthermore, the extreme use of fertilizer threatens to cause long-term degradation of essential natural systems and aquatic ecosystems. Industrial agriculture and the modern economy depend on the circulation of nitrogen and phosphorous compounds primarily as fertilizer and detergents and produce nitrogen dioxide through the combustion of fossil fuels. Unfortunately, the increased volume of these two elements is a serious source of pollution, and the potential to recycle and divert them from conventional waste streams remains underutilized.2 As long as these opportunities are not realized, municipalities will expend enormous resources treating wastewater, while industrial agriculture will continue to rely on synthetic fertilizers.

Urban agriculture applies many strategies that help recycle nutrients and can mitigate related environmental challenges by mimicking the closed-loop character of the natural nutrient cycle. These practices enable synergies between urban food production and urban waste management by supporting the use of alternative nutrient sources and the recovery of energy created as a byproduct of natural decomposition processes.

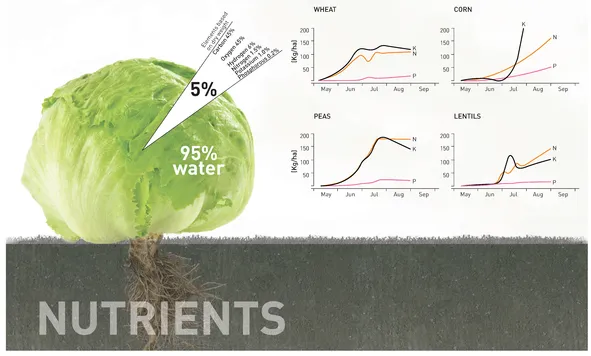

Nutrient Needs of Plants

While it is important to understand the larger environmental and global implications of the nutrient cycle, designers must also consider the resource and nutrient needs of plants when designing urban agricultural systems. Plants consist primarily of three non-mineral elements—carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O2). These elements are acquired from water (H2O) and from carbon dioxide (CO2) in the air and account for 99.5% of fresh plant material. Water alone makes up 95% of a plant, and its presence is therefore the main factor for plant growth (Figure 1.2). In the remaining dry matter, C accounts for approximately 45% of the mass, O2 for 40–45% and H for 5–7%. Plants absorb C in the form of CO2 during photosynthesis; transform it into glucose, which they store in their tissue; and produce O2 as a byproduct. Artificially elevating CO2 levels, referred to as CO2 fertilization, is a technique to increase plant growth and productivity. While plants create O2 during photosynthesis, they also use O2 for respiration during dark periods and to grow roots. Therefore plants require well-aerated soils or must receive aeration when grown in nutrient solutions.

While nutrients account for only 0.5% of a plant’s volume, these inorganic salts and trace minerals found in the soil (or provided in a growing solution) are necessary for plant growth. Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), sulfur (S), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) are considered macronutrients since they are required in relatively large amounts by plants. Copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), cobalt (Co), manganese (Mn), molybdenum (Mo), boron (B), and chlorine (Cl) are micronutrients required in relatively small amounts.

Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) are the primary nutrients needed by plants. The NPK rating system is used to specify the relative content of these chemical elements in a fertilizer. Each crop needs a slightly different composition of nutrients, which may change during different growth periods. Liebig’s Law of the Minimum states that growth is limited not by the total amount of resources available but by the scarcest resource—the nutrient in the smallest quantity relative to the plant’s need. Therefore it is important to provide all nutrients in sufficient proportions to prevent deficiencies and uncontrolled over-fertilization, which detrimentally affects plants and the environment.

▲ Figure 1.2

Chemical composition of a typical plant and the nutrient needs of different crops during their growing period

Data adapted from Howard M. Resh, Hydroponic Food Production: A Definitive Guidebook of Soilless Food-growing Methods (Mahwah, NJ: CRC Press, 2004), 35; International Plant Nutrition Institute, 1998.

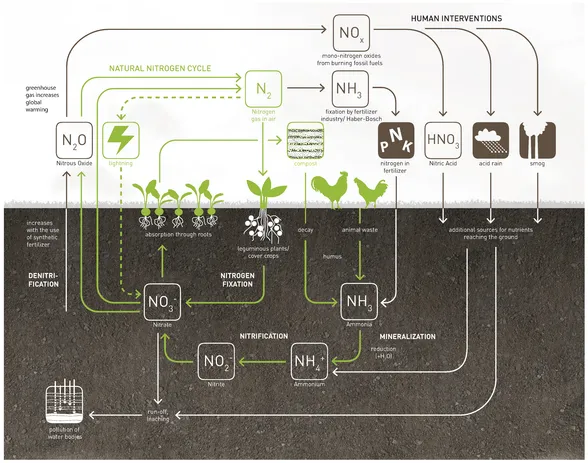

The Nitrogen Cycle

Nitrogen is vital for all living things. As a component of amino acids, it is necessary for the synthesis of proteins, enzymes, hormones, chlorophyll, and DNA. The atmosphere is the most important source of nitrogen, containing 78% of elemental nitrogen (N2), an inert gas that cannot be used by most plants directly. Only leguminous plants such as beans, peas, lentils, alfalfa, and clover, in symbiosis with rhizobium bacteria, can synthesize nitrogen from the air through nitrogen fixation. All other plants absorb nitrate-ions (NO3–) in the soil through their roots as their main nitrogen source. Decomposition of humus—the organic matter in the soil—and its mineralization into usable inorganic forms replenish the nitrogen content in the soil. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, human activities such as synthetic nitrogen fixation by the fertilizer industry and the uncontrolled exhaust of pollutants have doubled the amount of biologically available nitrogen readily absorbable by plants.3 This increased volume of nitrogen ends up in the wrong places with detrimental effects on the environment. Nitrogen compounds from agricultural runoff leach into groundwater and pollute aquatic ecosystems, leading to eutrophication (Figure 1.3). Too much nitrate in drinking water can lead to restricted oxygen transport in the bloodstream, which poses a health risk, especially to infants. Furthermore, the removal of excess nitrate in wastewater is very cost-intensive. Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a very potent greenhouse gas and the third largest contributor to global warming after carbon dioxide and methane.

▲ Figure 1.3

The nitrogen cycle—natural cycle and human interventions

Data adapted from Hannah Hislop, ed., The Nutrient Cycle: Closing the Loop (London: Green Alliance, 2007), 10.

High temperatures during combustion contribute to an increased creation of mono-nitrogen oxides (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). The higher the temperature during combustion, the more NOx is produced. Ammonia and nitrogen oxides contribute to smog and acid rain, which damage plants and increase the nitrogen ...