eBook - ePub

Work and Authority in Industry

Managerial Ideologies in the Course of Industrialization

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Work and Authority in Industry

Managerial Ideologies in the Course of Industrialization

About this book

Work and Authority in Industry analyzes how the entrepreneurial class responded to the challenge of creating, and later managing, an industrial work force in widely differing types of industrial societies: the United States, England, and Russia. Bendix's penetrating re-examination of an aspect of economic history largely taken for granted was first published in 1965. It has become a classic. His central notion, that the behavior of the capitalist class may be more important than the behavior of the working class in determining the course of events, is now widely accepted. The book explores industrialization, management, and ideological appeals; entrepreneurial ideologies in England's early phase of industrialization; entrepreneurial ideologies in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Russia; the bureaucratization of economic enterprises; and the American experience with -industrialization. This essential text will interest those in the fields of political science, industrial relations, management studies, as well as comparative sociologists and historians.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Work and Authority in Industry by Richard Bendix,Reinhard Bendix in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter 1

Industrialization, Management, and Ideological Appeals

The strongest is never strong enough to be always master, unless he transforms his strength into right, and obedience into duty.—J.-J. Rousseau, Social Contract.

a. Major Themes

This study deals with the role of ideas in the management of economic enterprises. Wherever enterprises are set up, a few command and many obey. The few, however, have seldom been satisfied to command without a higher justification even when they abjured all interest in ideas, and the many have seldom been docile enough not to provoke such justifications. This study deals with the ideas and interests of the few who have managed the work force of industrial and business enterprises since the Industrial Revolution. It is particularly concerned with ideas which pertain to the relations between workers and employers or their agents. Such ideas have been expressed by employers, financiers, public-relations men, personnel specialists, general managers, engineers, economists, political theorists, psychologists, government officials, policemen, political agitators, and many, many others. All these men have had in common a direct concern with the problems of industrial organization, whether or not they have worked in some managerial capacity themselves.

Industrialization has been defended in terms of the claim that the few will lead as well as benefit the many. It has been attacked in terms of the assertion that both the exploiting few and the exploited many are made to suffer, body and soul. The most rapidly advancing industrialized nations, the United States and Soviet Russia, are heir to these conflicting ideological antecedents. Since this conflict is the point of departure for the present study, it is appropriate to formulate at the beginning the common core of the two entrepreneurial or managerial ideologies which have been used in the advance of industrialization.1

In the West industrialization has been defended by ideological appeals which justified the exercise of authority in economic enterprises. Qualities of excellence were attributed to employers or managers which made them appear worthy of the position they occupied. More or less elaborate theories were used in order to explain that excellence and to relate it to a larger view of the world. The exercise of authority would also be justified in terms of the “naturally” subordinate position of the many who obey. To this a further reference to the social order was usually added, holding out a promise to the many who with proper exertion might better themselves or even advance to positions of authority. These ideas appear to lack humane appeal. A creed which expounds the identity of virtue and success will strengthen the conviction of those who are convinced already. And the related admonition to the “poor” to exert themselves as their “betters” have, will be reassuring to those who have arrived. Such appeals express the interests of a group of men, whose power and social position are more or less secure by virtue of their successful leadership of economic enterprises. But it is probable that these ideas have also had a strong appeal for those who spend their daily life under the authority of the very employers whose achievements are celebrated. Indeed that authority has been defended on the ground that each man is free to enjoy what he can acquire on his own, and the promise of freedom based on exertion has excited the human imagination. But this position has also been attacked on the ground that the few are rewarded while the many are deprived, that the promise of freedom is spurious as long as it implies the risk of starvation as well as each man’s dependence upon an irrational market and an inhuman machine. Still, the ideological defense of industrialization has helped to structure our image of the social world—within the orbit of Anglo-American civilization. The following study examines this ideological defense, first at the inception of industrialization, and then in its contemporary setting.

In Soviet Russia industrialization has been advanced by ideologies of management, which originated as a critique of industry. That critique pointed to two disastrous consequences which society must avoid or undo. Through their pursuit of gain men had been alienated from their fellows; the relations among them had come to depend upon the cash-nexus. And through the division of labor industrialism had subjected the individual producer to the degrading domination of the machine, depriving him of the satisfaction which the craftsman enjoyed. To undo these consequences it was necessary to afford all men the opportunity of doing their work as participants in a common undertaking. Accordingly, the commands of managers and the obedience of workers should receive their justification from the subordination of both groups to a body which represented managers and workers so that each man would obey policies he had helped to formulate. Hence, the exercise of authority by the few and the subordination of the many would be justified by the service each group rendered to the achievement of goals determined for it. And the relations between employers and workers would be regulated in conformity with an authoritative determination of the role of each.

If the Western spokesmen of industry can be identified by the expression of material interests, their opponents in Russia may be identified by the assertion that their interests are identical with the higher interests of mankind. Communism has owed its strength to the articulation of grievances against the industrial way of life. The belief that the pursuit of gain alienates men from their fellows, that the rich are depraved and the poor are deprived, constitutes a potent appeal to the dissatisfactions of the many and facilitates identification with humanity. Yet this attack has been incorporated in a managerial ideology, which combines these negative appeals with the ideal of collective ownership and planning. Karl Marx had capped his attack upon capitalism with the proposal to restore “real” freedom. Men “should consciously regulate production in accordance with a settled plan” so that they would carry on their work with the means of production in common.2 All should own and plan as well as work, so that all might be free. These ideas have been defended on the ground that men can find personal fulfillment only when they own their tools and consciously direct their own activity. They have been attacked on the ground that such personal participation in collective ownership and planning is nominal only, that the promise of personal fulfillment is spurious as long as each must carry on his work in accordance with dictates and in the absence of privacy. This, then, is the other ideology which this study examines, again at the inception of industrialization and in its contemporary setting. For we are confronted with the paradox that the ideas with which the effects of industry were condemned have been incorporated in ideologies of management which today prevail within the orbit of Russian civilization.

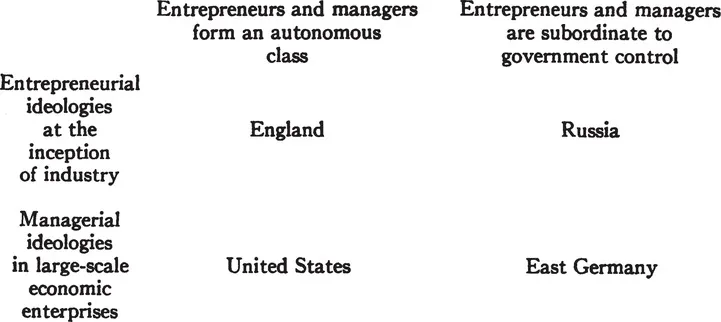

1 propose to examine the major entrepreneurial ideologies in the early phases of industrialization in England and in Russia (Chapters 2 and 3). Subsequently, I shall examine the major managerial ideologies which have evolved in the recent industrial history of the United States and which are used currently in the Soviet Zone of East Germany (Chapters 5 and 6). The link between my consideration of “then” and “now” is formed by a chapter on the bureaucratization of industry (Chapter 4).

During the early phase of industrialization a new way of life is in the making and an old way of life is on the defensive. In this respect I shall compare England and Russia during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For those who initiate the development of industry must overcome the opposition of many groups, and the ideas they advance concerning the relations between employers and workers will appear as part of the whole effort to gain acceptance for, and to facilitate, the development of industry.

While the initiation of industry involves everywhere a break with the past, it also involves quite dissimilar patterns of developments. In taking my cue from the present division of the world into East and West, I have chosen two such patterns of industrialization. These may be distinguished in the sense that English industrialization resulted principally from the struggle of a rising entrepreneurial class, while in Russia the interaction among social classes which was connected with industrialization was continually subject to autocratic intervention and bureaucratic controls.

This contrast between a society in which those who govern industry form a more or less autonomous social class, and a society in which entrepreneurs are subordinate to governmental controls, has endured till the present day; but the internal organization of economic enterprise has undergone profound changes, which have consisted, broadly speaking, in the multiplication of technical and administrative tasks as well as in the lengthening of the rank-order of authority in industrial organizations. As a result the tasks of management have increased in number and complexity, and the ideas concerning the relations between employers and workers have become a part of the effort to solve these managerial tasks more successfully. Accordingly, the outline of this study may be represented by the following schematic representation:

It will be useful to state the of this study by giving an over-all description of the comparisons and contrasts implicit in this scheme.

I. At the inception of industry entrepreneurial ideologies are similar in certain respects. The problems of industrial organization and labor management will appear as part of the whole effort to gain acceptance for, and thereby to facilitate, the development of industry. During this early phase, employers and their agents have little experience with these problems; the consideration of management as a technical problem does not belong, therefore, to this early phase. Rather the practices and ideologies of management may be understood as a part of the effort to promote industry in a relatively hostile environment. The ideas which are used to justify the exercise of authority in industry are employed primarily to justify the entrepreneurs before the public at large. That public consists typically of two major social groups, a politically dominant aristocracy and a newly recruited industrial work force. Spokesmen for these groups often oppose industry with the same arguments, but their reasons for these arguments differ significantly. For members of a ruling aristocracy industrialization constitutes a threat to their political dominance as well as to their way of life. For members of a newly recruited industrial work force industrialization constitutes a threat to their established way of life and hence provides an opportunity to make invidious contrasts between that way of life and the new opportunities, demands, and deprivations laid upon them. Hence, the entrepreneurial ideologies during the initial phases of industrialization are primarily justifications of industry and of the leaders of industry which are called forth by this opposition of antagonistic social groups. Therefore, a good bit more is involved than the analysis of ideological trends. It is necessary to identify who the early entrepreneurs were and what their relationship was to the “ruling classes” in the society in which industrialization was initiated. Relations between these entrepreneurs and their workers are strongly affected by the traditional master-servant relationships. It is necessary to characterize the latter before analyzing how the practices and ideologies of industrial management are differentiated from them and developed further. Moreover, the industrial entrepreneurs, the workers in their enterprises, and the ruling social groups are engaged in social and political interaction in their respective efforts to come to terms with the industrial way of life. Each group seeks to do so in a manner it regards as advantageous (or less disadvantageous) to itself. It is necessary to characterize this interaction in order to understand the terms of the controversy in which the ideological weapons are fashioned by those who initiate the development of industry.

II. At the inception of industry entrepreneurial ideologies differ in certain respects. Such differences arise from the historical legacies and the social structures of the countries under consideration. The early phase of industrialization in England was characterized by a rising entrepreneurial class, which fought for social recognition and political power at the same time that it developed its enterprises, and recruited and disciplined an industrial work force. In Russia this early phase was characterized by the governmental promotion of enterprises and by the dependence of many, mutually antagonistic groups upon the government in terms of administrative and police measures which would aid their economic activities as well as the recruitment and disciplining of the work force.

In the West, the ideas which have been used to advance industrialization have reflected and affected the actions of entrepreneurs and managers of industry. These leaders of enterprise developed or made use of ideas which enhanced their social cohesion and active unity as a social class. Such cohesion and unity arise from the common interests of similarly situated individuals. These individuals may be combined in an organization or they may be divided by conflicting interests; they may exert great power when some issue unites them for the time being. But their unity or diversity in thought and action are never wholly integrated by a hierarchical organization. Social classes are groups of individuals whose common interests in the social and economic order now and again give rise to unifying ideas and united actions but whose cohesion is more or less unstable. This lack of stability is reflected in the development of entrepreneurial ideologies, which have been reformulated in response to changing industrial and social environments. Such reformulations or changes may be considered as more or less flexible adaptations to changing conditions by men of action whose underlying purpose remained the advance of practical interests and the increase of material gain. Ideological adaptations of this kind cannot be considered simply as an outgrowth of self-interest, for a man must judge what is to his interest, and many factors other than interest may influence his judgment. In nineteenth-century England entrepreneurs and managers of industry were on the whole free to pursue their interests as they saw them. And the strategies of argument with which they and their spokesmen advanced and defended entrepreneurial activities were strongly affected by the historical legacies which permitted men of substance to formulate and pursue their interests in common.

These considerations do not apply to the industrialization of Russia, however. The ideas and actions of entrepreneurs and managers who advanced industrialization in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Russia were subjected to the more or less thorough control of a governmental bureaucracy and to the principle of Tsarist supremacy. This characteristic of Russian civilization may be called an “external bureaucratization” of industry, which should be distinguished from the “factory legislation” which is familiar to us from the industrial history of England and of other countries. For “factory legislation” was typically concerned with stipulating the conditions under which the interaction between employers and workers would take place independently. Such legislation laid down what employers cannot do and what workers can do; it typically expressed an effort to balance the strength of the two parties by legislative means. But the external bureaucratization of Russian industry attempted to do more than this. It stipulated the rights and duties of both parties not only by prohibiting certain actions, but also by ordering what should be done. And in addition the government superimposed on the authority relationship between employers and workers incentives and controls of its own. The purpose was to enhance the authority of managers over workers and the control of the state over managers, as well as to increase the obedience and productivity of the workers.

III. The development of the industrial way of life has transformed this initial setting of entrepreneurial activity in Russia as well as in the countries of Western civilization. One principal difference between then and now is that today the industrial way of life has become accepted (in the countries under consideration), and that the ideologies pertaining to industrial organization and labor management are no longer directly involved in the struggle for or against industrialization. To be sure, the attempt to justify industry before the public at large remains; the leaders of industrial enterprises and their spokesmen still find it necessary to justify their activities and defend them against their critics. This continued defense, however, has become a matter of public relations, concerned with propagandizing the achievements of technology and production which are generally accepted.

A second principal difference between then and now consists in the change from entrepreneurial to managerial ideologies. The ideologies of those who lead the large-scale enterprises of modern industry have come to serve new ends, which have resulted from a process of internal bureaucratization. The increase in the tasks of industrial management was relatively slow in making itself felt. For a long time these tasks remained in the hands of subordinate employees or contractors, who in turn relied upon the traditional relationships between masters and servants. As we shall see, there has existed, roughly speaking, an inverse relation between the diminishing strength of these traditions and the increasing division of labor in the technical and administrative organization of industrial enterprises. This increasing size and complexity of industry have transformed the authority relationship between managers and workers, and hence the internal organization of industry.

The internal bureaucratization of economic enterprises has had significant consequences. The few who command must control but cannot superintend the execution of their directives. They are bound to delegate more authority as the size of enterprises and the number of persons in positions of some responsibility increase. The delegation of authority has its counterpart in the technical and administrative specialization of those who execute as well as of those who control the implementation of directives. For specialization implies that those lower down in the hierarchy of command know more in a limited field than those who are above them. Of course, it is often said that the more highly placed have the more general view in addition to their greater authority. It should be noted, however, that their subordinates tend to acquire power even without authority to the extent that their expertise removes them from the effective control of their superiors. The tasks of management have increased in the sense that the increasing discretion of subordinates has had to be matched by strategies of organizational arrangements, material incentives, and ideological appeals if the ends of management were to be realized. In this respect the managerial ideologies of today are distinguished from the entrepreneurial ideologies of the past in that managerial ideologies are thought to aid employers or their agents in controlling and directing the activities of workers.

In the early phase of industrialization there was no difference between appeals to the workers (if the employers took the trouble to make such appeals) and the effort to win public acceptance for the economic activities with which the employers were identified. Entrepreneurial ideologies reflected the interaction among social classes brought about by industrialization. In modern industry management has had to concern itself, ide...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- 1. Industrialization, Management, and Ideological Appeals

- PART ONE

- PART TWO

- PART THREE

- Credits

- Author Index

- Subject Index