![]()

1

“TO COVER UP THE TRUTH WOULD BE A WASTE OF TIME”:

Introduction

’Things back then were horrible and I think that because I fought like a man to survive I made it somehow easier for the kids coming out today. I did all their fighting for them. I’m not a rich person. I don’t have a lot of money; I don’t even have a little money. I would have nothing to leave anybody in this world, but I have that—that I can leave to the kids who are coming out now, who will come out into the future. That I left them a better place to come out into. And that’s all I have to offer, to leave them. But I wouldn’t deny it. Even though I was getting my brains beaten up I would never stand up and say, ‘No don’t hit me. I’m not gay; I’m not gay.’ I wouldn’t do that. I was maybe stupid and proud, but they’d come up and say, ‘Are you gay?’ And I’d say, ‘Yes I am.’ Pow, they’d hit you. For no reason at all. It was silly and it was ridiculous; and I took my beatings and I survived it.”

—Matty

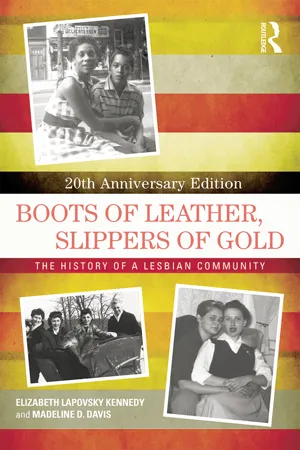

Working-class lesbians of the 1940s and 1950s searched for and built communities—usually around bars and house parties—in which they could be with others like themselves. Like the woman quoted above they did not deny their lesbianism, despite severe consequences; and today many of them judge their actions as having contributed to a better life for gays and lesbians. Their self-reliance and dream of a better world placed them solidly in the democratic tradition of the United States. But what happened to that independent spirit and hope when it was awakened in working-class lesbians whose very being was an anathema to American morality? Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community tells that story. We document how working-class lesbians—African Americans, European Americans, and Native Americans—created a community whose members not only supported one another for survival in an extremely negative and punitive environment, but also boldly challenged and helped to change social life and morals in the U.S.1

Popular culture, the medical establishment, affluent lesbians and gays, and recently, many lesbian feminists have stereotyped members of this community as low-life societal discards and pathetic imitators of heterosexuality, and therefore hardly self-conscious actors in history.2 Our own first-hand acquaintance with some older working-class lesbians, who told lively and dramatic stories about the joys and pains of their experiences, led us to question this view. We suspected that they had forged a culture for survival and resistance under difficult conditions and had passed this sense of community on to newcomers; in our minds, these were signs of a movement in its prepolitical stage.3 Our research has reinforced the appropriateness of this framework, revealing that working-class lesbians of the 1940s and 1950s were strong and forceful participants in the growth of gay and lesbian consciousness and pride, and necessary predecessors of the gay and lesbian liberation movements that emerged in the late 1960s.

John D’Emilio points out that the ideology of gay liberation was based on an intriguing paradox.4 It was a movement that called for an end to years of secrecy, hiding, and shame; yet its rapid growth suggests that gays and lesbians could not have been completely isolated and hidden in the time period just prior to the movement’s inception. Gay liberation built on and transformed previously existing communities and networks. In his own work, D’Emilio explores in detail how the homophile movement, a network of organizations formed in the 1950s advocating peaceful negotiation for legal change and social acceptance, laid the groundwork for gay and lesbian politics of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The homophile movement, however, was very small and held itself separate from the large gay and lesbian communities that centered in bars and house parties; its history, therefore, can tell only part of the story. D’Emilio’s work suggests, but does not itself explore, that bar communities were equally important predecessors.

Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold is the first book-length study of a mid-century bar community. Focusing on Buffalo, New York, the book aims to explore how the culture of resistance that developed in working-class, lesbian bars and house parties contributed to shaping twentieth-century gay and lesbian consciousness and politics. Our approach is that of ethno-history: a combination of the methodology of ethnography—the intensive study of the culture and identity of a single community—with history—the analysis of the forces that shaped how that community changed over time, using as our primary sources oral histories of Buffalo lesbians.

We have chosen to focus on working-class lesbians because we view them as having had a unique role in the formation of the homophile and gay liberation movements. Like virtually every other aspect of modern social relations, lesbian social life and culture differed according to social class. Lesbians who were independently wealthy and not dependent on society’s approval for making a living and a home could risk being open about their lesbianism with few material consequences. But this privilege also meant that their ways of living had limited benefit for the majority of working lesbians.5 Middle-class lesbians who held teaching and other professional jobs had to be secretive about their identity because their jobs and status in life depended on their reputations as morally upstanding women. So, they, too, could not initiate the early effort to make lesbianism a visible and viable opportunity for women, nor develop a mass political movement that could change social conditions.6 By contrast, working-class lesbians pioneered ways of socializing together and creating intimate sexual relationships without losing the ability to earn a living. Who these working-class lesbians were and how they developed forms of community that had lasting influence on the emergence of the homophile, gay liberation, and lesbian feminist movements are central issues in this book.

The focus on community rather than the individual is based upon our assumption that community is key to the development of twentieth-century lesbian identity and consciousness. Even though lesbians or gays did not live in the same areas, or work at the same place, they formed communities that were primary in shaping lesbian and gay culture and individual lives by socializing together. In the 1960s, sociologists and psychologists already had come to realize that what many had taken as the idiosyncratic behavior of gays and lesbians was really a manifestation of gay and lesbian culture formed in the context of bar communities.7 But the ideology characterizing gays and lesbians as isolated, abnormal individuals remains so dominant that the importance of community in twentieth-century working-class lesbian life has reached few people and has to be affirmed and explained regularly to new audiences.

For the purpose of this book, we define the Buffalo working-class lesbian community as that group of people who regularly frequented lesbian bars and open or semiopen house parties during the 1940s and 1950s. Such a definition raises problematic issues about boundaries. Were those who went to the bars once a year “members” of the community in the same way as those who went once a week? Was there a single national lesbian community, since some Buffalonians regularly visited other cities and experienced a shared culture? Was there more than one community in Buffalo since it definitely had subcommunities with somewhat different cultures? Did African-American lesbians have more in common with African-American lesbians in Harlem in the 1950s than with European-American lesbians in Buffalo? We have no easy answers for such questions, but they are explored recurrently throughout the book.

By focusing on working-class lesbian communities that centered in bars and open house parties, we are highlighting the similarities between lesbians and gay men, since gay men and lesbians socialized together in such locales. Nevertheless, we decided to focus primarily on lesbians in order to ask questions from a lesbian point of view. Our aim is to understand the imperatives of lesbian life in the context of the oppression of homosexuals and of women. Later in the book, in the context of information on patterns of socializing and then again in the conclusion, we will consider the extent to which gay men and lesbians can be considered a single community.

Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold covers a crucial period in the development of lesbian community, slightly more than two decades from the late 1930s to the early 1960s. Since our method is oral history, we are forced to start in the 1930s because that is as far back as our narrators’ memories reach.8 We believe, however, that World War II was a critical period for the formation of the Buffalo working-class community, and, therefore, the late 1930s is an appropriate starting point. The study ends before the rise of gay liberation and feminism.

Within this period, significant changes occurred in lesbian life. In Buffalo in the 1930s, the public lesbian community was small and fragmented. Lesbians had a difficult time finding others like themselves and felt extremely isolated. During the 1940s and in the context of World War II, the lesbian community stabilized and began to flourish. There were approximately the same number of gay and lesbian bars in Buffalo during the 1940s as there are today. In the 1950s, despite the witch-hunts of gays and lesbians, the rigidification of sex roles, and the general cold-war atmosphere, the lesbian community became more defiant and continued its pursuit of sexual autonomy for women. The community also became more complex. The relatively autonomous African-American and European-American communities became integrated to the extent that each had some contact with the other, and certain bars and house parties were frequented by a racially mixed crowd. In addition, the community became class-stratified with a more upwardly mobile group and a rough and tough blue-collar group each going its separate way. Each of these groups developed a somewhat different culture and different strategies for carving out space and respect in a hostile heterosexual world.

The concern of this book is to document these changes in detail, to understand what they meant for lesbian culture, consciousness, and identity, and to explore the connection between particular kinds of consciousness and the homophile movement on the one hand and gay liberation on the other. We also seek answers to why particular changes occurred at particular times. One of our underlying questions is, Who makes lesbian history? Although as oppressed people lesbians were deeply affected by the dominant social system, the degree to which they acted on their own behalf needs to be understood. To what extent did the activities of lesbians shape their developing social life and politics? Toward this end, we examine the activities of lesbians within their own community as well as their interactions with the larger society.

At first we were swept away by the exciting interconnections between socializing in bars and developing lesbian culture and tended to relegate sex and relationships to a position of lesser importance in the formation of identity and consciousness. This impulse was based in part on the conceptual division between the public (social life and politics) and the private (intimacy and sex), which characterized nineteenth-century society, and has remained deeply rooted in modern consciousness. With women’s move out of the home and the eroticizing of social life in general, the twentieth century has seen a realignment of the public and the private. The emergence of gay and lesbian communities was related to this shift and contributes to a more subtle understanding of the relationships between these two spheres.

The life stories of our narrators as they talked freely about sexuality led us to what should have been immediately obvious: Although securing public space was indeed important, it was strongly motivated by the need to find a setting for the formation of intimate relationships. By definition, this community was created to foster intimacy among its members and was therefore built on a dynamic interconnection between public socializing and personal intimacy. This study therefore encompasses social life in bars and house parties and sexual and emotional intimacy, and the interconnections between them. It asks such questions as: How does women’s sexuality develop outside of the restraints of male power? What was the role of community socializing in the development of lesbian sexuality? How did lesbians balance an interest in sex and a desire for emotional closeness? What was the impact of community social life on the longevity of lesbian relationships?

All commentators on twentieth-century lesbian life have noted the prominence of butch-fem roles.9 Before the 1970s, their presence was unmistakable in all working-class lesbian communities: the butch projected the masculine image of her particular time period—at least regarding dress and mannerisms—and the fem, the feminine image; and almost all members were exclusively one or the other. Buffalo was no exception. As in most places, butch-fem roles not only shaped the lesbian image but also lesbian desire, constituting the base for a deeply satisfying erotic system. Beginning this research at a time when the modern feminist movement was challenging gender polarization and gender roles were generally declining in importance, we at first viewed butch-fem roles as peripheral to the growth and development of the community. Eventually we came to understand that these were at the core of the community’s culture, consciousness, and identity. For many women, their identity was in fact butch or fem, rather than gay or lesbian. The unique project of this book, therefore, is to understand butch-fem culture from an insider’s perspective.

Why should the opposition of masculine and feminine be woven into and become a fundamental principle of lesbian culture? Several scholars have addressed this question. Modern lesbian culture developed in the context of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when elaborate hierarchical distinctions were made between the sexes and gender was a fundamental organizing principle of cultural life. In documenting the lives of women who “passed” as men, Jonathan Katz argues that, in the context of this nineteenth-century polarization of masculinity and femininity, one of the few ways for women to achieve independence in work and travel and to escape passivity was by assuming the male role.10 In a similar vein, Jeffrey Weeks holds that the adoption of male images by lesbians at the turn of the century broke through women’s and lesbians’ invisibility, a necessity if lesbians were to become part of public life.11 Expanding this approach, Esther Newton situates the adoption of male imagery in the context of the New Woman’s search for an independent life, and delineates how male imagery helped to break through the nineteenth-century assumptions about women’s natural lack of sexual desire and to introduce overt sexuality into women’s relationships with one another.12

We agree with these interpretations and modify them for the conditions of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. During this period, manipulation of the basic ingredient of patriarchy—the hierarchical distinction between male and female—continued to be an effective way for the working-class lesbian community to give public expression to its affirmation of women’s autonomy and women’s romantic and sexual interest in women. Butches defied convention by usurping male privilege in appearance and sexuality, and with their fems, outraged society by creating a romantic and sexual unit within which women were not under male control. At a time when lesbian communities were developing solidarity and consciousness, but had not yet formed political groups, butch-fem roles were the key structure for organizing against heterosexual dominance. They were the central prepolitical form of resistance. From this perspective, butch-fem roles cannot be viewed simply as an imitation of heterosexual, sexist society. Although they derived in great part from heterosexual models, the roles also transformed those models and created an authentic lesbian lifestyle. Through roles, lesbians began to carve out a public world of their own and developed unique forms for women’s sexual love of women.13

Like any responsible ethnography, this book aims to take the reader inside butchfem culture and demonstrate its internal logic and multidimensional meanings. We will document the subtle ways that lesbian community life transformed heterosexual models, pondering the inevitable and fascinating confusions: What does it mean to eroticize gender difference in the absence of institutionalized male power? Is it possible to adopt e...