![]()

1 Supply and demand

Keywords: economic concept of supply and demand, application to housing markets; Barker Report view of reducing price of housing through increasing supply across tenures; defining affordable housing; effective demand and need; acute housing need; overcrowding; the management of housing need; supply issues; areas of over-supply; postscript to Chapter 1: can planning reforms solve the problems of supply and demand?

Introduction

If demand meant the total quantum of housing required, and if supply was exactly balanced with this quantum in relation to number, location, household size and personal resources, there would be no housing need, as it would be met either immediately or in short order. You cannot be in need of what you have, or of what would be made available the moment you require it. Of course, the moment before you obtain something which is necessary to you, you need it, but in the context of housing, we are talking about a lack of some duration. In the real world, however, there is not a balance between housing demand, used broadly, and supply, and this imbalance gives rise to distressing human circumstances such as homelessness and rooflessness which, sadly, are far too common across the world.

Why is this? Or what gives rise to this imbalance? This can be answered on many levels. One answer, which is not generally applicable spatially or over time, is that it might be believed that the human population has grown, or tends to grow, at a faster rate than the discovery or production of available resources and if housing is a (secondary) resource, demand will therefore inevitably outstrip supply. This was the view proposed by Thomas Malthus in the eighteenth century, and has been immensely influential in social and economic theory since propounded in his An Essay in on the Principle of Population published in 1798 and reissued in six editions to 1826 (Malthus, 1798). Essentially, he suggests that the growth of human population tends to be geometric (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, etc.), as opposed to the increase in resource exploitation which is likely to follow at best an arithmetic progression (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, etc.), so that ultimately, population growth exceeds the means to support it, resulting in war, famine and disease. This is a very gloomy picture of human societal development redolent of an apocalyptic horror movie, but may very well end up being verified, as human population growth has indeed followed a geometric progression over recorded history. Yet there is no evidence that it is remotely true for human society in developed Western countries. There is plenty of vacant land available on which housing could be built, and many empty dwellings which could provide shelter and sustenance. There is a crude surplus of agricultural production over consumption in Western economies, and a seemingly limitless supply of natural resources, sustainable and even fossil, to support human life to a reasonable standard even at present growth rates. Additionally, although the world population appears to be growing exponentially, the same is not true of many individual developed nations, and so whereas eventually we may globally outstrip the means of sustenance, there is no reason to think that we will do so here and in the near future.

Another thought is that there is something inevitable about unmet housing need, which arises from the operation of laws of economics, and which leads to the necessity of state intervention if it is believed that housing is basic to human survival, and that the promotion of human survival is a basic mark of a civilised society and we wish to promote civilisation. This arises from the observation that housing costs something to produce and maintain, and that providers will seek to recoup their outlay plus a profit for supplying it to reimburse their effort. It also proceeds from the observation that it is not in the interests of producers to manufacture or make available unlimited quantities of what they make, or even enough to meet actual demand, by which (in this context) I mean total unmet requirement.

To understand why unmet housing need might be seen to be inevitable, we need to consider the ‘laws’ of supply and demand propounded by classical economists. The model is that the price of anything will be determined by the interaction of supply and effective demand, which means demand from consumers who are willing and able to pay for something. The idea is that, in a competitive market situation, the price of a product or service is the result of the price which consumers are willing to pay meeting the price at which the vendor is willing to sell. Consumers may start by bidding too low – in this case, suppliers will not make the goods available. Alternatively, suppliers may price their products too high to attract consumers, in which case they will have to come down. The idea is that eventually the product attains its equilibrium price, where the price offered by consumers meets that at which suppliers are willing to make the good available. Within this generalisation, four laws are recognised by many economists. Simplifying, they are:

1. The equilibrium price and quantity will increase where demand increases and supply is level.

2. Equilibrium price and quantity will decrease if demand decreases and supply is level.

3. Where supply increases and demand is level, the equilibrium price will decrease and quantity will increase.

4. If supply decreases and demand is unchanged, this will lead to higher prices and lower quantities.

These laws are often attributed to Adam Smith, which considered the dynamics of price in his seminal work, The Wealth of Nations (Smith, 1776), and have long been accepted as a basis for pricing theory, although they have been varied and refined over the years. On the basis of these ‘laws’ we can deduce that there will always be some consumers who are unable to bid for the ‘equilibrium price’ – if all could, it would mean that the price of the product would probably be far below the cost of producing it, even in the case of very cheaply produced housing. It is also obvious that those with very low resources or none would be outbid by other consumers, since the supply of the product is limited, if only by the capacity of producers to develop housing.

That said, it should be possible to reduce the price of the product by influencing effective demand levels, and by increasing supply. If effective demand for housing in an area drops, the price decreases, although interestingly enough, because the market is segmented (for example between private renting and owner-occupation), a falling housing market for sale may well lead to the withdrawal of owner-occupied products from the market and an increase in the availability of private rented accommodation, as people have to live somewhere. It is no accident that in areas where house prices are high in relation to wages, there is often a buoyant rental market, as in many parts of London. Here again, rental prices may be high due to increased demand resulting from the former factor, and in this case, many households will be excluded from the owner-occupier and private rental market.

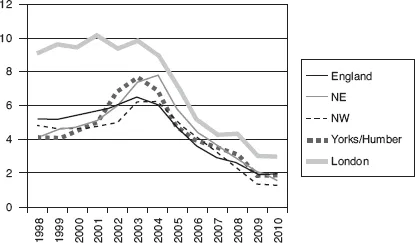

The influence of classical economic thinking has had a marked effect on national housing policy in England since the 2000s, when Kate Barker produced her seminal report on how to assist in meeting future housing needs by market intervention or stimulus in 2004 (Barker/ODPM, 2004). In essence, the analysis is straightforward. Housing need (by which I mean housing requirement which is unmet by the market) is not uniform across the country. This can be deduced purely on the basis of homelessness statistics – looking at the numbers of homeless acceptances by local authorities per 1,000 population. According to the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) housing statistics in Table 772 on statutory homelessness: households accepted by local authorities as owed a main homelessness duty, by region, 1998 to 2011, the acceptance rate in London was 0.9 in quarter three of 2011, compared to 0.4 in the less economically vibrant North East, and against a national figure of 0.6. The rate in London has been consistently higher than nationally since the statistical series was started in 1998, sometimes by a factor of two, and also has outperformed less economically active regions such as the North East and North West at least since that date. If homelessness can be taken as a surrogate for housing need used in the sense of unmet requirement, we can reasonably infer that housing need is relatively higher in London than elsewhere (see Figure 1.1).

The overall reduction in numbers per 1,000 is due largely to changed government policy in the form of the encouragement of prevention strategies and housing options services to deflect housing need away from the social housing sector since around 2003. The relevant aspect of Figure 1.1 to note is the regional relativities in rate at any one time. How, then, is it possible to increase supply relative to demand in areas of most acute housing need?

Figure 1.1 Trends in homelessness acceptances by region, 1998–2011 (number/1,000 households by year)

Source: CLG, Table 772, available at: www.communities.gov.uk/housing/housingresearch/housingstatistics/housingstatisticsby/homelessnessstatistics/livetables/, viewed 21 January 2012.

The Barker review, Delivering Stability: Securing our Future Housing Needs (Barker/ODPM, 2004) was commissioned April 2003. Its terms of reference were to conduct a review of issues underlying in the lack of supply and responsiveness of housing in the UK, to examine the role of competition, capacity, technology and finance of the house-building industry, and to establish the interaction of these factors with the planning system and the government’s sustainable development objectives. The review concluded that, taking as the baseline the level of private sector build in 2002–2003, 140,000 gross starts and 125,000 gross completions, reducing the trend in real house prices to 1.8 per cent would require an additional 70,000 private sector homes per annum; and to reduce the trend in real house prices to 1.1 per cent, an additional 120,000 private sector homes per annum would be required.

It also concluded that an increase in supply of social housing of 17,000 homes each year was required to meet the needs among the flow of new households, and that there was a case for providing up to 9,000 a year above this rate in order to make inroads into the backlog of need. If all of the additional build were carried out in the South East, an additional 120,000 homes per year would take around 0.75 per cent of the total regional land area. One wonders how this would fit in with the localism agenda on planning!

Increasing land availability through the planning system was thought to be the prime mover for this quantum increase:

Central to achieving change is the recommendation to allocate more land for development. This certainly does not mean removing all restraints on land use, on the contrary the review advocates more attention be given to ensuring the most valuable land is preserved. But house-builders would have greater choice as to which sites to develop, increasing competition. And it would also allow a quicker and more flexible response to changing market conditions on the upside … This calculation assumes that 60 per cent will be built on brownfield sites, and that dwellings will be built at a density of 30 per hectare. It also includes an allowance for related infrastructure.

(Barker/ODPM, 2004, p. 6)

This sounds excellent in theory, at least as a way of stabilising house prices so that more people can afford to buy rather than rent, and possibly reducing the call on the social or affordable housing sectors. However, it does presuppose the capacity of developers to produce homes in the quantity required, and the notion that 60 per cent of new homes should be built on brownfield sites deserves attention. Brownfield sites are those which have already been developed but where the initial use is redundant, so permitting redevelopment. Generally, they are within urban contexts, with the advantage of proximity to infrastructure, but in many cases such sites are expensive to prepare for development due to the need for decontamination (more so in the case of severely polluted ‘redfield’ sites). The corollary of this is that around 40 per cent of new provision should be built on greenfield (previously undeveloped) sites. The vast majority of these sites are in rural locations. If house price stabilisation in areas of high demand is a key objective, this will inevitably mean building in relatively sacred environments such as the Green Belt, close to centres of economic prosperity, and not in locations in the middle of nowhere where arguably the environmental and social impact might be somewhat less.

The Barker approach is also rather simplistic in that local housing market dynamics are affected by many other factors than supply. Regional income profiles vary significantly, while labour is not perfectly mobile. There is also the negative feedback aspect of development: build more houses in an area and its attractiveness as a destination may decrease, with the consequence that it may not be possible for those putting money into such schemes to realise their investment quickly enough, or at the level required. Then there are the vagaries of local economies: there have been well-observed general trends in the rise and decline of regional economies, and the underlying factors are relatively well known. The economic decline of the North East, for example, between 1950 and 1980 was a product of the loss of key multiplier industries such as shipbuilding, steelworks and coal mining, whereas the economic growth of London and the South East is largely down to the burgeoning finance and information industries and location vis-à-vis Europe’s golden triangle. It could therefore be predicted that this would stimulate a migration of working-age people from the North East and other declining peripheral regions to the South East, with consequent increases in demand for housing in the recipient area. But how permanent is such a trend, and what technological or other changes in the market may intervene both within and between regions to alter this? And should a housing market stimulation policy be based on economic trends which may well reverse with the development of the location-less information economy which is just as at home in Newcastle as it is in London?

However, it should be admitted that supply of market housing is an important factor in attempting to deal with the knotty question of how much affordable housing should be provided, where and when, hence the growing significance of housing market assessments in examining the strategic housing requirement at a variety of spatial levels, from the local authority to the national level, and it is to these that we no...