eBook - ePub

Housing and the New Welfare State

Perspectives from East Asia and Europe

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The changing nature and significance of housing provision within welfare states is considered in this timely book. With housing playing an increasingly important role in welfare provision, the new welfare state emerging in different parts of the world is being developed in the context of individual asset accumulation and the private ownership of housing. Housing and the New Welfare State shows that housing is becoming critical to asset-based welfare not only in Western Europe but also in the six East Asian housing systems that are a major focus of the book. Chapters by leading East Asian scholars provide analysis of housing policies in Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, China and Taiwan. Also examined are the 'four worlds' of welfare and housing; the causes and consequences of the shift from tenants to home owners in the old welfare states of Britain and other parts of Western Europe; and the growth of the property-owning welfare state as a theme running through contemporary policy in both East Asia and Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Housing and the New Welfare State by Richard Groves, Alan Murie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Four Worlds of Welfare and Housing

The focus of this book is upon housing and the changing nature and significance of housing provision within the context of welfare states. The book does not offer a new perspective on the welfare state itself but develops the debate about the significance of housing within the welfare state. It does not present an analysis of health, or education, or social security, or social welfare systems but the underlying contention is that existing debates about welfare state systems have neglected the importance of housing. To some extent, this neglect has weakened the analysis of traditional welfare state systems but more importantly, it presents an ethnocentric view of welfare state systems, it inadequately represents the types of welfare states that have developed in East Asia and it risks understating the significance of developments in housing provision for the changing nature of the welfare state.

The starting point for the book then, is a view that, rather than perceiving that there are three major welfare state types (Esping-Andersen, 1990), we should at least embrace a fourth – that associated with the East Asian economies and referred to by Jones (1990), Sherraden (1997) and others. There is a literature which adds a southern European, family centred welfare state model (Allen et al., 2004), and there are a number of discussions of hybrid welfare state systems; however it is our intention to focus upon the four worlds of welfare capitalism which emerge most strongly from the literature. Within that, the intention is to focus upon the fourth of these four worlds – the East Asian case. It is in that context that housing, rather than being a wobbly pillar of the welfare state, or a marginal element in the welfare state system, emerges as of much more central importance. The East Asian model puts property development and ownership in a much more significant position, but, as will be seen later from this book, rather different approaches have emerged in individual East Asian countries.

The intention then is to explore the nature of this distinctive and different model, and to move the understanding of the importance of housing within the developing welfare states of these economies beyond what is available elsewhere in the literature. However our intention moves beyond this. We are concerned also with the extent to which traditional welfare states, the other three worlds of welfare capitalism identified by Esping-Andersen and particularly the UK welfare state, have been evolving over a period of more than 50 years. Our aim is to draw attention to the significance of developments in housing policy in those older welfare states; and to suggest that the nature of the traditional welfare state is changing and in some respects is developing characteristics associated with the East Asian model. The property owning welfare state has a very different composition to the traditional welfare state. Its concern with expanding property ownership rather than citizenship rights marks a significant break in the approach to welfare provision and a move away from corporatist or egalitarian redistributive models towards a more individualized model in which the accidents of market-determined changes in the value of property affect the opportunities and life chances available to households to a much greater extent than in the past.

This chapter sets out some of the starting points for this discussion. It refers briefly to existing typologies of welfare states and of housing provision systems – starting with a brief discussion of the existing literature on welfare state regimes and referring principally to the important contribution by Esping-Andersen (1990). Against this background we then provide an overview of some of the considerations arising if more attention is placed on the experience from East Asia; and if we reflect upon the direction of change and especially the increasing role of individual property ownership in the new welfare model emerging through the East Asian experience, and in some of the more traditional welfare systems.

Welfare State Regimes

There is a strong and influential literature which categorizes different countries and groups them according to the nature of their welfare state systems. However this literature has limitations because it takes both too ethnocentric a view and too narrow a view of the nature and operation of the welfare state. The focus on cash benefits and social security arrangements fails to do justice to the nature of welfare state systems in which access to services in-kind – including housing services – is significant.

Perhaps the most influential contribution made to comparative studies of welfare states was by the Danish political scientist Gøsta Esping-Andersen (1990). His book The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism provided a sustained and detailed analysis of differences in the welfare regimes of different countries. He argued that simple comparisons of the levels of expenditure on welfare in different countries do not give an adequate picture of the different nature of their welfare systems. Countries with relatively high expenditure are not necessarily involved in major redistribution between income groups but could simply be confirming and rewarding existing patterns of inequality. To understand the differences between welfare state systems we need to move beyond these simple quantitative comparisons and assess the nature and operation of welfare states. At the same time Esping-Andersen argued that the development of welfare state regimes owes more to the specific historical and political development of different countries than it does to stages in economic development or global processes. The fact that countries all develop welfare states of some kind does not demonstrate that they develop because of some logic of industrialization or economic development. He rejected views that welfare states emerge as a result of universal physiological forces, technological determinism or as a consequence of industrialization. He also rejected the view that they are a necessary and inevitable consequence of political development and the growth of democracies. Esping-Andersen argued that welfare states are the product of local and national pressures rather than of reified social constructs or of global influences. Consequently welfare state systems will have different attributes and Esping-Andersen sought to make systematic comparisons between different welfare states and to understand the nature of these differences in terms of the different kinds of political processes which are common to similar regimes.

It is not the main intention of this book to provide a critique of this analysis. It is clear that it has been successful in stimulating debate but has very considerable weaknesses. Some of these were implicitly acknowledged by Esping-Andersen himself and have been discussed subsequently. Even in 1990 he acknowledged that certain countries were more difficult to fit into his typology and that the particular period in which he carried out his analysis may affect the results. If he had carried out the analysis at different points in time he would have produced different results. For this book our concern is the narrow basis on which he operationalized his approach to welfare states and the results that emerged.

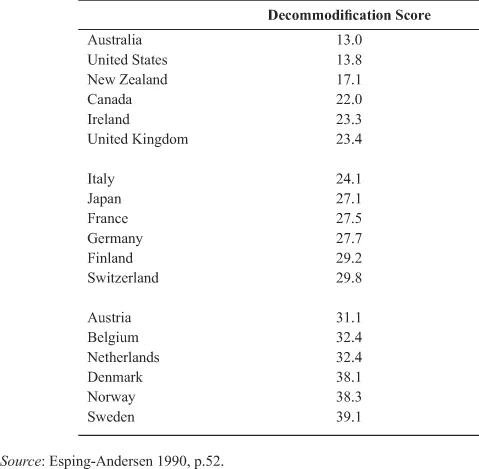

Esping-Andersen emphasized the importance in the welfare state of rights and specifically of citizenship rights determining access to services. He associated this with a notion of decommodification and the extent to which people are entitled to services because of their citizenship status rather than because of their income. In this sense welfare states loosen the pure commodity status of products or services. Esping-Andersen (1990) stated: ‘Decommodification occurs when a service is rendered as a matter of right and when a person can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market’ (p 22). He went on to operationalize this notion of decommodification and to establish the extent to which different systems enabled people to maintain their livelihood without reliance on the market. In doing this, his focus was purely upon income related benefits. He focused upon old age pensions, sickness benefits and unemployment insurance and was concerned to examine the eligibility rules, levels of income replacement and the range of entitlements offered in different countries. In effect he assessed how generous, universal and redistributive old age pensions, sickness and unemployment insurance systems were and how far different welfare states enabled people in older age, sickness or unemployment to maintain their livelihood. Esping-Andersen provided a decommodification score for each of the three areas identified, and the aspect of his work which emerged from this analysis and has commanded most attention was the combined decommodification score, reproduced as Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Rank-order of welfare states – combined decommodification, 1980

From this Esping-Andersen referred to three kinds of welfare state regimes. The lowest decommodification score related to liberal regimes that were minimalist in their approach and had the most limited income replacement and the most limited decommodification. It was argued that these welfare state regimes aimed to minimize the role of the state to that which was essential to maintain economic efficiency. The leading examples of this type of welfare state were in North America and Australasia.

He contrasted this liberal welfare state regime with a second group of corporatist welfare states which were more generous than the liberal regimes but were not concerned with redistribution. They were largely designed to support and preserve status differentials and key institutions including the Church and the family. The key examples of these kinds of corporatist welfare state systems were France, Germany and Italy.

Finally, Esping-Andersen identified welfare state regimes which he described as social democratic and in which decommodification was much greater; there was a universalist approach and redistribution and the promotion of equality were key aims of the welfare state. Denmark, Norway and Sweden were the principle examples in this group.

There is some literature that has added to Esping-Andersen’s portrayal of the welfare state and this includes criticisms of the narrow range of welfare benefits that he referred to. While the framework for analysis and the focus on process and path dependency is a good one, the operationalization through a limited number of income benefits does not provide an adequate basis to typify different welfare state systems. There is a neglect of education, health, housing, transport and public utilities. There are other social security measures that are not included: child benefit and allowances, fiscal measures, and disability allowances. There are other measures of integration associated with minority groups and different types of households, including lone parents. Because social security measures are designed to complement and integrate with one another and with other related measures, a selected subset of measures may provide a distorted view. In addition to the concern that the particular time period selected influenced the results, the neglect of the role of other institutions such as the family, not-for-profit organizations and occupational welfare is referred to. As Table 1.1 indicates, the range of countries included in this is also limited. The analysis is based upon Northern and Western Europe, North America, Australasia and Japan. Only Japan is included from East Asia.

Eastern European regimes had distinctive welfare states at this stage because of the nature of their communist regimes. Nevertheless, there is a danger that Esping-Andersen has referred to countries which share some similarities in cultural, political and economic histories. How far does the approach hold up when looking beyond this range of countries?

Housing in the Welfare State

One of the areas of welfare state provision which is missing from Esping-Andersen’s operationalization of decommodification is housing. The combined decommodification score in Table 1.1 is not affected by the extent of non-market housing provision, eligibility for that housing, and the extent to which people are able to continue to live in such housing even when they would not be able to afford the market price for it. It is also unaffected by the nature of health, education and other services: the discussion of welfare states is not comprehensive.

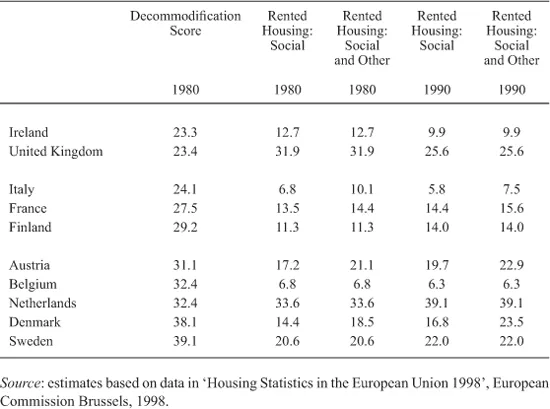

What happens if housing is included in the picture? One way of addressing this is simply to look at the size of the not-for-profit sector as an indicator of the extent of decommodified housing in different countries. When we do this the liberal welfare states referred to above tend to have very limited public and not-for-profit housing sectors and the redistributive regimes have larger not-for-profit and public sector housing provision. However, the fit is not a very good one – as Table 1.2 indicates. The data in Table 1.2 refer to European countries and come from a European Commission source. It is important to be cautious about the precision of these statistics: the original source presents statistics which divide the dwelling stock according to tenure (rented, owner occupied and other) and then divide the rented category between social, private or other. What is reproduced in Table 1.2 is a calculation based upon the stock identified as rented in the first place and, within the rental dwelling stock, as either social or social and other. The most obvious omission from this is co-operative housing, which would not be categorized as rented in the first place. To the extent that countries such as Sweden have substantial co-operative housing sectors, the decommodification of housing in this Table may be understated. In 1980, however, the statistics for Sweden indicated that 16 per cent of the overall dwelling stock was in the ‘other’ category, and this is the highest of any of the countries included. Consequently the extent to which decommodification is understated will be small and we believe these figures are a good indication of the relative levels of decommodification in different countries.

Table 1.2 Welfare states, decommodification and housing, 1980 and 1990

It is immediately apparent that, referring either to 1980 or to 1990, there is not a good fit between Esping-Andersen’s decommodification scores and the levels of decommodified housing indicated by social rented housing or social and other rented housing in Table 1.2. If the expectation was that the highest levels of decommodified housing would be in those countries with the highest decommodification scores in Esping-Andersen’s analysis, then this expectation is not realized. The most obvious exceptions are Belgium within the redistributive welfare state group (with only 7 per cent of rented housing in 1980), and Denmark (with 14 per cent), compared with the United Kingdom in the liberal welfare state group with 32 per cent of social rented housing in 1980. We know, however, that Australia, the USA, New Zealand and Canada all have low rates of social rented housing, so it may be that in the liberal welfare state group the United Kingdom is the exception, with Ireland to a lesser extent also an exception. These are both countries with a legacy of direct housing provision. They are also countries where housing finance and the way it interacts with taxation and benefit payments may mean that the high level of decommodification of housing is directly associated with the lower decommodification score in Esping-Andersen’s analysis. For example, Britain is unusual in operating a housing benefit scheme which has provision to meet 100 per cent of rent costs. The benefit rates applying at the present time do not assume that any contribution is made from basic benefits towards rent. In other countries there is generally an assumption that some part of base benefits contributes to rent. This means that base benefits are set at a higher level elsewhere and in the UK are set at a lower level (see Kemp, 1997).

While it is clear that the fit between Esping-Andersen’s decommodification and housing decommodification is not a good one, there are some other elements that can be noted from the data in Table 1.2. The corporatist welfare states do not show such a great variation in the level of decommodified housing. Taking social housing in 1980, the variation is from 6.8 to 11.3 compared with the variation amongst the redistributive welfare states, from 6.8 to 33.6 or amongst the liberal welfare regimes from 12.7 to 31.9. This would be consistent with the view that the corporatist welfare states tend to have had similar approaches to housing provision, with relatively lower levels of direct provision. In contrast, the liberal and redistributive regimes embrace very different approaches to housing provision in both cases.

There are also some significant differences between the data for 1980 and 1990. The corporatist welfare states show little change between these two dates. In two cases there seems to be a slight increase in decommodified housing, and in one case a decrease. The two liberal welfare states both show a marked decrease. Amongst the redistributive welfare states there was an increase in all cases except for Belgium. Again this highlights the extent to which the date chosen will impact upon the results of the analysis. If this analysis were to be taken forward ten years, the share of decommodified housing would have declined amongst some of the redistributive welfare states if not all of them.

From this initial perspective, it is worth exploring issues about decommodification of housing more fully. The United Kingdom in 1980 had a very large decommodified housing sector (one in three of all properties). Ireland in contrast had a very small decommodified housing sector. While this fits with the decommodification score in Esping-Andersen it neglects the fact that a very large part of Ireland’s housing stock was built by the state and there has been a long history of privatization or subsidized sale. Consequently, the current housing structure obscures a much more substantial decommodified housing programme.

Most countries in Europe emerged from World War II with serious housing shortages, a damaged housing stock and in some cases a legacy of nineteenth century housing, much of which would subsequently be cleared or improved to more modern standards. In conditions of post-war shortage, there were strong political pressures for local and national governments to become deeply involved in housing, however small had been their pre-war role in this area of policy.

Britain was the first country in Western Europe to embark on a subsidized public sector housing programme. This began as early as 1919 and gathered pace throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In the years before and after 1919, however, there was a view of public housing as a temporary phenomenon that would not be needed when conditions returned to ‘normal’ and housing was much less a feature of the consensus that built up around policies for health, education and social security that were the foundations of the post-World War II welfare state.

This was true also in other Western European countries, as shown in work by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (1966) that put forward a classification of housing policy regimes in the member countries of the Economic Commission for Europe;1 and which became well known through the publication in 1...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Four Worlds of Welfare and Housing

- 2 The Singapore Model of Housing and the Welfare State

- 3 The State-managed Housing System in Hong Kong

- 4 The State and Housing Policy in Korea

- 5 Housing and State Strategy in Post-War Japan

- 6 From Socialist Welfare to Support of Home-Ownership: The Experience of China

- 7 Taiwan’s Housing Policy in the Context of East Asian Welfare Models

- 8 From Tenants to Home-Owners: Change in the Old Welfare States

- 9 The Property Owning Welfare State 195

- Bibliography

- Index