1

Framing the Story

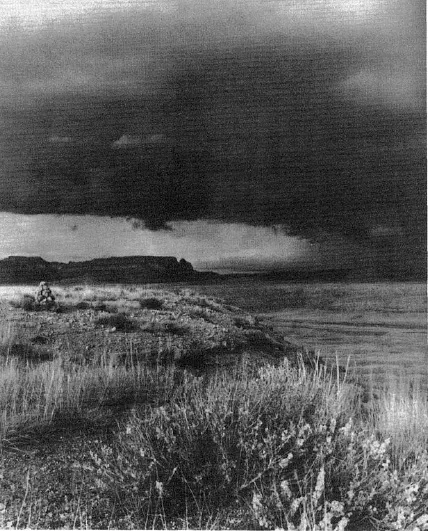

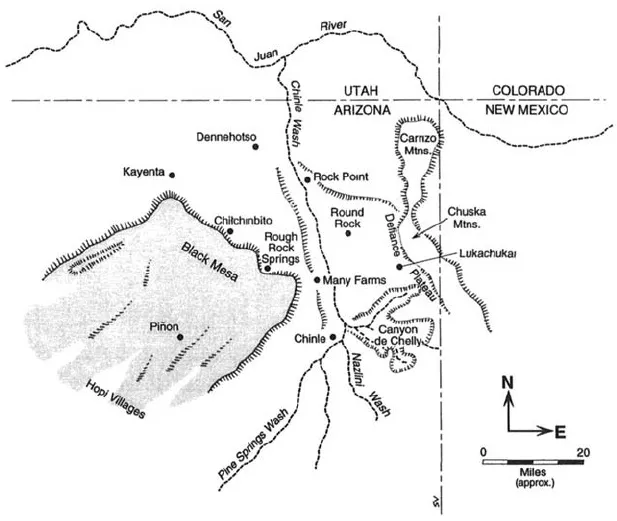

From its origins in the Pagosa Mountains in Colorado, the San Juan River forms an arch within the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States—that point in the high desert where the borders of the modern states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah meet. As the arch descends southwestward toward the Colorado River, it is met by Chinle Wash, which winds for nearly 100 miles through a landscape of red rock buttes and mesas, multi-hued canyons thick with cottonwoods, and small family farms. This is the heart of the Navajo Nation. It is the place where people settled with their livestock after leaving Dinétah, the Diné (Navajo) homelands near present-day Farmington, New Mexico. It was also the site of some of the most intense Navajo resistance when, in the autumn of 1863, Colonel Kit Carson led a scorched earth campaign through the Chinle Valley and adjoining Canyon de Chelly, burning fields and homes, slaughtering family sheep, and precipitating the exile and incarceration of 8,000 Navajos at Fort Sumner, New Mexico.

U.S. Highway 191 runs through the Chinle Valley now. Driving north from Chinle, Arizona, a town of about 3,000, one sees, beyond the modern housing and tourist facilities built to accommodate visitors to Canyon de Chelly, the forested mountains of the Defiance Plateau and, nearer the road to the west, a long and narrow red rock ridge, behind which rises the tan and blue-streaked contours of Black Mesa.1 On each side of the road are traditional hogans (in Navajo, hooghan), or earth and log homes, alongside frame houses, mobile homes, and family fields. In summer, the fields lie green with corn, squash, melon, and alfalfa.

About 15 miles north of Chinle is the smaller settlement of Many Farms and a sign pointing west that reads, “Rough Rock, 15 miles.” This is the way I entered the Rough Rock community more than two decades ago as a non-Indian hired by the Rough Rock School Board to help develop a K-12 Navajo bilingual/bicultural curriculum. I have purposefully introduced the story of the Rough Rock Demonstration School this way, mapping an outsider’s route into the community and school.

I first took the turn-off to Rough Rock on a crisp, blue-skied March afternoon in 1980. Dr. Robert A.Roessel, Jr., the school’s cofounder and first director, was helping to develop Rough Rock’s Navajo Studies program, and he invited me to assist. Recently relocated from my hometown of Columbus, Ohio, I was a young graduate student in social-cultural anthropology at Arizona State University (ASU), where I had been working with Robert Roessel, who also was serving as a visiting professor at ASU’s Center for Indian Education. Previously, I had worked as a youth counselor, teacher, and educational liaison for the Fort McDowell Yavapai-Apache community near Phoenix. In the context of that work and my studies, I learned of the ground-breaking initiatives in Indian education taking place at Rough Rock. Of my first glimpse of this famous place, I wrote in my field journal:

Leaving Many Farms, there is a steep, short climb to the top of the ridge. Above lies a sweep of blue-green foothills and sandstone bluffs. Rising about 500 feet above these bluffs are the dark, steep cliffs of Black Mesa. The school is nestled at the base of the cliffs. I immediately recognized the familiar water tower and elementary school complex from the many photographs of Rough Rock in books.

Rough Rock School in 1980 had been in operation for 14 years. Founded in 1966, the school grew out of Federal War on Poverty programs. By the time I moved to Rough Rock in the fall of 1980 it already had been established as an innovative program in Indigenous education—the first school to have an all-Navajo governing board and the first to teach Navajo language and cultural studies. Numerous books and articles had been written about the school, and Rough Rock’s Navajo Curriculum Center, started in 1967, had published dozens of texts and teachers’ guides on Navajo language, culture, and history. But the school board and staff felt the Navajo curriculum was incomplete, and in 1980 they submitted a proposal for a 3-year Federal grant to fill in the gaps. The grant was funded and I was hired as a curriculum writer for the Materials Development Project which, in addition to my position, funded a Navajo language and culture specialist, an artist, and a secretary/editorial assistant—all members of the community.

I lived at Rough Rock for the next 3 years. In addition to working on the curriculum, and with the school board’s consent, I completed a dissertation on the school’s bilingual/bicultural program (McCarty, 1984; 1987; 1989). In 1987, while employed by the Arizona Department of Education’s Indian Education Unit, I was invited back to Rough Rock to work as a consultant to bilingual teachers and the elementary school principal on a new bilingual/bicultural program they were developing with the Hawai’i-based Kamehameha Early Education Program (KEEP; see Begay, Dick, Estell, Estell, McCarty, & Sells, 1995; Vogt, Jordan, & Tharp, 1993). Although I currently teach at a university 450 miles away, I have continued to work at and with the people of Rough Rock ever since, traveling there regularly to conduct ethnographic observations of bilingual classrooms and to collaborate with teachers, teacher aides, parents, and administrators on the bilingual/bicultural program.

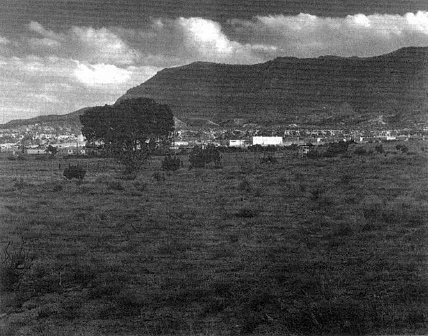

FIG. 1.2. Rough Rock Elementary School and dormitories, 1983. (Photograph by Fred Bia, courtesy of Rough Rock Community School.)

In the course of this long-term work, my family and I established lifelong friendships with many people at Rough Rock. I long ago stepped “over the line” between researcher-writer and friend—a line that is, I believe, artificial and obstructive to long-term ethnographic and applied research and that, at any rate, would have been impossible to sustain for more than two decades of involvement with this small, kin-centered community (see Valdés, 1996, p. 13).

This is not a disinterested or dispassionate account. The impetus for writing comes from my desire to consolidate my long-term work with the school, and a request from the school board and staff. In 1996, Rough Rock marked its 30th anniversary as the first American Indian community-controlled school. A great deal of enthusiasm preceded this event, and the school board wanted a book that would chronicle the history of the school. I was both humbled and excited to be asked to work on such a book, but from the beginning I believed it should be a collaborative effort. In September 1995, I met with then-school board president Ernest W.Dick and several school staff members to discuss the possibilities. They made it clear that they wanted a balanced account— one that thoughtfully confronted a full range of experiences and processes glossed with the value-laden terms, “success” and “failure” (see, e.g., Varenne & McDermott, 1998). As my colleagues at Rough Rock described it, the goal in this book was to reflect on the school’s history. “In 30 years, what were some of the accomplishments and problems? We want to establish a real experience,” Ernest Dick said. “The way I look at it, it’s how Indian education actually survived.”

These words hint at the theory of history that guides this account. This is not a history of universals or absolutes, but an “effective history” in the way Nietzsche (1887/1968) and, a century later, Foucault described: It “deals with events in terms of their most unique characteristics” (Foucault, 1984, p. 88; see also Eisenhart, 1998, p. 395). It is a history that uses local memory to challenge dominant historical narratives, and to re-imagine the possibilities within Indigenous schooling (Lipsitz, 1990; McLaren & Tadeu da Silva, 1993). This is a history concerned not with continuity but with disruption and discontinuity; not with detailing intrinsically knowable events, but with understanding the complicated forces that positioned one community at the center of a movement for Indigenous education control.

From this perspective, Ernest Dick’s words in 1995 were prophetic, for, as I discuss below, Rough Rock almost did not survive its 30th year. But in the fall of 1995, hopes were high, and we—a voluntary team of teachers, school board members, administrators, and other school staff who expressed an interest in the project—began to plan the book. The centerpiece would be a series of oral history interviews of community members and people outside Rough Rock who had a role in the school’s evolution. High school students would act as videographers for the interviews. “The students think it’s wonderful,” their teacher reported at an initial meeting of the team. “They’re really excited. They’ve written questions. They want to be part of it. And they say, ‘Oh, Rough Rock’s important?’ ‘Yeah, you know, we’re talking about it being the first community school.’ I think this could be an experience that really could touch them…. It brings the story full circle.”

The methodology for the interviews and this study as a whole is discussed more fully in the following chapter. Here, let me briefly summarize the events that preceded the writing. We—the self-identified “book project team”—began the first series of interviews in January 1996. In March I returned to Rough Rock for additional interviews. On April 22, a day before I was scheduled to return for a final series of community interviews, a group of about 100 parents, students, and staff staged a protest at the school, preventing buses from entering the elementary school parking lot and calling for the removal of certain administrators and school board members. The rift within the community growing out of this event has only begun to heal; the causes are enormously difficult and complex, and they relate directly to the issue of self-determination and local education control. I analyze the protest later in the book, recognizing, as Michelle Fine points out, that “the risk lies in romanticizing of narratives” and retreat from analysis (1996, p. 80). Two immediate impacts of the protest were to curtail the interviews and dampen the entire anniversary celebration. Rough Rock marked its 30th year with massive reductions in school enrollment and staff, and with considerable uncertainty about whether it would, in fact, survive.

There was a time when I felt equally uncertain about writing this account. Clearly the events of the spring of 1996 dashed the collaborative efforts originally envisioned for this project, as cooperation among various community members and some school staff became untenable. But I have been fortunate to remain on good terms with all my associates at Rough Rock. All have been adamant in wanting this story to be told. “If you don’t do it, Terri,” one colleague at the school told me, “no one will.”

I have no illusions that this is the case, but I know that the stories told to us by elders and other community members are gifts, intended to be shared. Like others who have written on minoritized education from a position outside the community, I have struggled with how to frame those stories—with, as Guadalupe Valdés writes, “finding a voice with which to write…respectfully and in friendship” (1996, p. 13). As I present the account that follows, I do so respectfully and in friendship and solidarity, with the hope that this story of Rough Rock will provoke change by illuminating the conditions that enable or constrain Indigenous and other minoritized communities from providing a decent, humane, and uplifting education for their children. “This is an opportunity to recognize the importance of what was started 30 years ago,” one school administrator said, “and to rededicate ourselves to that.” “This is an opportunity,” a bilingual teacher added, “to say what are the hopes and dreams of Rough Rock.”

_____________

1Black Mesa also is known as Black Mountain or Dziłijiin (literally, mountain, it extends black, the one; Young & Morgan, 1987, p. 360), but Black Mountain has come to mean the area near the Rough Rock Trading Post, and Black Mesa the area as a whole. Black Mesa is the English term used most frequently by Rough Rock residents.

2

People, Place, and Ethnographic Texts

My mother and father came upon this land so many years ago. I don’t remember it that well. I think I was about 5 years old. Here we stay on our land that we have had for so many years. Here we have our homes. Our sheep, horses, and cattle—these came here with us. We made life here. My parents said that there will be life here and the people will live here. My father has gone now as well as my mother. Now there are only those of us who are the children. That is how we live.

—Mae Hatathli, Rough Rock, March 1996

In her 70s when she gave this account, Mae Hatathli has witnessed great change in the land around Rough Rock and the life it sustains. To a large extent those changes have been wrought by the school. As a starting point for examining those changes and the larger fight for self-determination they both summoned and represent, this chapter sketches Rough Rock’s physical and social landscape. I also explain the procedures for datagathering, the sources of information used to construct this text, and my role in presenting the story that follows.

TSÉ CH’ÍZHÍ

Tsé Ch’ízhí—Rough Rock—is named for the rocks near a spring at the northern base of Black Mesa, which stretches for 60 miles across northern Arizona (see Fig. 2.3).1 On the southern edge of the mesa lie the 12 Hopi villages where people from Rough Rock traditionally traded mutton and other goods for Hopi peaches and paper-thin piki (blue cornmeal) bread. This high, arid, beautiful land supports prickly pear cactus, agave, sage, piñon pine, juniper, and a variety of shrubs and grasses. Above Rough Rock, on Black Mesa, elevations reach over 8,000 feet, and grassy meadows adjoin deep stands of ponderosa and piñon pine.

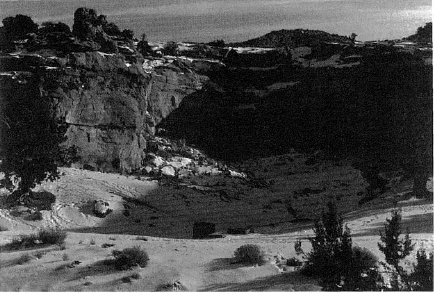

FIG. 2.2. Rough Rock Springs in winter, c. 1983. (Photograph by Fred Bia, courtesy of Rough Rock Community School.)

In summer, temperatures on the plateau below the mesa can reach into the 90°s, with periodic torrential rains. Those rains are welcomed for the forage they provide for livestock, and in a good fall season the tawny tufts of wild grasses and a profusion of yellow flowering shrubs and sunflowers line the roadsides. Winters below the mesa are cool but relatively mild, with occasional snowstorms. “On top”—the common reference to settlements on Black Mesa—winter can be isolating and severe. Reverend Vern Ellis, a Quaker missionary who had lived at Rough Rock for almost 30 years when I resided there during the 1980s, recalled the “big snow” of 1973–74, when food and supplies had to be airlifted to families on top. “Lots of people were stranded on top,” he said. “It was really critical.” With luck, spring brings more rain, and for a month or so, fierce winds. If rain is plentiful, by May the land is carpeted with breathtaking expanses of green grass, golden chamisa or snakeweed, and tiny purple flowers.

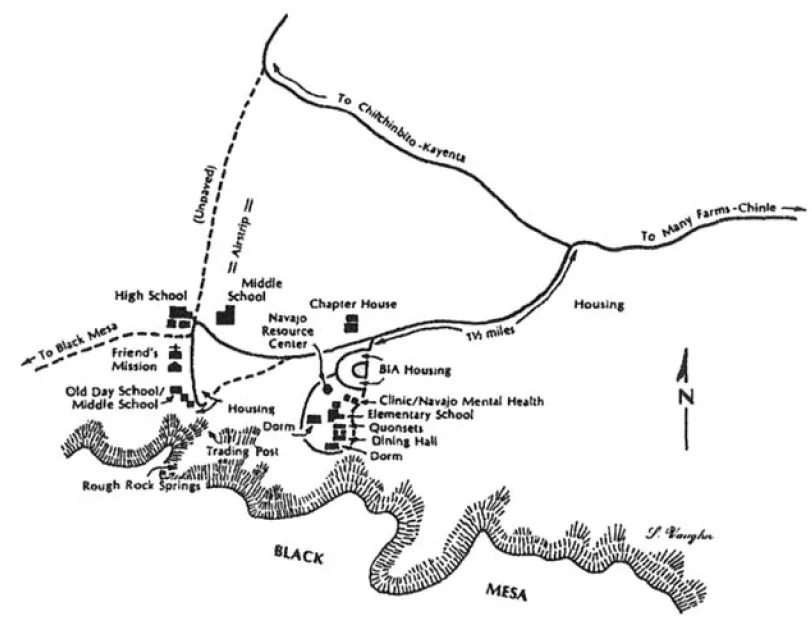

At the junction of the Many Farms highway and the road leading into Rough Rock, a sign reads: “Rough Rock Community School—Diné Bi’ólta.” The road first passes by a cluster of nearly identical stucco employee houses. Beyond this, a water tower imprinted with bold black letters, “Rough Rock,” rises against the blue-green face of Black Mesa. Beneath the tower sit the elementary school, dormitories, cafeteria, plant management services building, a clinic, and a large log hogan in which cultural activities take place. Recently, a Navajo Studies Center was established in a double hogan near the entrance to the elementary school campus, with a huge metal identifying sign marking the prominence attached to this program. Surrounding the campus are horse-shoe-shaped rows of employee housing and mobile homes. This is the elementary school compound; encircled by wire fence, its physical features resemble those of many small communities across the reservation.

Farther down the road from the junction are the chapter house— the seat of local government for the 1,500 community members—and rodeo grounds. About a quarter-mile further, at the end of the road, are the high school and middle school. Here, where the road forms a T, a graded dirt road leads to the top of Black Mesa. The pavement continues toward an old stone building and another double hogan. From the 1930s to the 1960s, this was a Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) day school. Today, these buildings house the school board conference room, school administrative offices, and a school post office. Just west of the administration building is the Friends Mission, and to the east, adjacent to the spring, is the Rough Rock Trading Post, also used as the community post office. A third cluster of tribally financed housing is situated across the road (see Fig. 2.4).

FIG. 2.3. Traditional Rough Rock-Black Mesa land use area.

FIG. 2.4. Rough Rock school complex and surrounding facilities.

Beyond the school, a network of extended family households, locally called camps, dot the land in all directions. Accessible by dirt roads and for the most part not visible from the highway, each household includes one or more frame houses and/or hogans, a ramada or shade house, a stock corral, and often an agricultur...