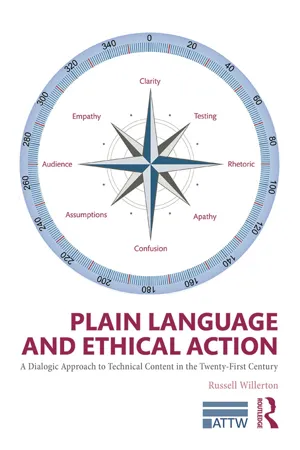

Plain Language and Ethical Action

A Dialogic Approach to Technical Content in the 21st Century

- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Plain Language and Ethical Action

A Dialogic Approach to Technical Content in the 21st Century

About this book

Plain Language and Ethical Action examines and evaluates principles and practices of plain language that technical content producers can apply to meet their audiences' needs in an ethical way. Applying the BUROC framework (Bureaucratic, Unfamiliar, Rights-Oriented, and Critical) to identify situations in which audiences will benefit from plain language, this work offers in-depth profiles show how six organizations produce effective plain-language content. The profiles show plain-language projects done by organizations ranging from grassroots volunteers on a shoe-string budget, to small nonprofits, to consultants completing significant federal contacts. End-of-chapter questions and exercises provide tools for students and practitioners to reflect on and apply insights from the book. Reflecting global commitments to plain language, this volume includes a case study of a European group based in Sweden along with results from interviews with plain-language experts around the world, including Canada, England, South Africa. Portugal, Australia, and New Zealand.

This work is intended for use in courses in information design, technical and professional communication, health communication, and other areas producing plain language communication. It is also a crucial resource for practitioners developing plain-language technical content and content strategists in a variety of fields, including health literacy, technical communication, and information design.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Understanding Plain Language and Opportunities to Use It

- Is plain language an ethical concern?

- What processes and procedures can help plain-language writers do ethical work that helps their audiences?

An Overview of the Worldwide Movement toward Plain Language

Early Developments in Plain-English Style

| Century | Development in plain-English style |

| Fourteenth Century | The Host in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales exhorts the learned Clerke of Oxenford to speak plainly so the pilgrims may understand him (McArthur 1991, 14). |

| Sixteenth Century | Writers of technical books in English in the sixteenth century used plain style for their audiences. But because writers used plain-English style outside of traditional literary genres, this style choice did not receive much attention (Tebeaux 1997). |

| Seventeenth Century | The first person to refer to “plain English” as opposed to florid, ornate English may be Robert Cawdrey, who compiled the first known English dictionary in 1604. His Table Alphabeticall uses English words to define difficult words borrowed from languages like Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Cawdrey’s stated audience for the dictionary was women. Without formal education, women had “no easy way of appreciating the layer of Latinity that had formed, as it were, along the top of traditional English” (McArthur 1991, 13). |

| Francis Bacon prominently advocated for plain style in science, as did the Royal Society. Women writers such as Margaret Cavendish and Jane Sharp used plain style to reach their audiences (Tillery 2005). |

Influences on the Plain-Language Movement in the Early- and Mid-Twentieth Century

New Momentum in the 1970s

Responses in the US to a Particular Type of Unclear Language

| Area of activity | Influence on the plain-language movement |

| US Government | Maury Maverick, once chairman of the Smaller War Plants Corporation, wrote a memo in 1944 to everyone in the corporation requesting that lengthy memoranda and “gobbledygook” language be replaced by short and clear memoranda. Maverick coined the term “gobbledygook” after recalling the sights and sounds of a bearded turkey strutting and gobble-gobbling about (Greer 2012, 4). |

| In 1953, Stuart Chase wrote The Power of Words, which includes a chapter bemoaning gobbledygook in bureaucracies, law, and universities. In 1966, John O’Hayre of the Bureau of Land Management released 16 essays on plain-English writing for business and government in Gobbledygook Has Gotta Go (Redish 1985, 128). | |

| UK Government | Ernest Gowers advocated for civil servants to communicate clearly. A training pamphlet he wrote in 1943 later grew into the book Plain Words in 1948. Gowers published a companion reference book, The ABC of Plain Words, in 1951. Gowers combined those two books into The Complete Plain Words in 1954, a volume reprinted many times (Kimble 2012, 51–52). |

| In 1946, British author George Orwell complained about the “slovenliness” of writing about government and politics in modern English. In his classic essay, “Politics and the English Language,” which has appeared in writing anthologies for decades, Orwell (2005) provides six succinct rules to help writers remove vagueness and pomposity. | |

| US Education and Research | Although studies of factors affecting the readability of texts date back as far as the 1890s in the US, research on readability increased notably after researchers surveyed and tested adult literacy. The military started literacy surveys in 1917; other agencies began testing civilians and students soon after (DuBay 2004). |

| Prominent researchers from this era include Rudolph Flesch, who released his Reading Ease formula in 1948 (Kimble 2012, 49–50), as well as William S. Gray and Bernice Leary, Irving Lorge, Edgar Dale and Jeanne Chall, Robert Gunning, Wilson Taylor, and George Klare (DuBay 2004). | |

| Researchers have developed hundreds of readability formulas over time. Experts have long debated how and whether these formulas should be used, especially because the formulas focus on a text’s surface features—numbers of syllables, words, and sentences. Readability formulas are important in the history of plain language because they have influenced understandings of plainness and clarity and because some laws and regulations require plain-language texts to meet particular readability scores. |

| Government entity | Development in the plain-language movement |

| US Government | In 1972, President Richard Nixon decreed that the Federal Register should use layman’s terms and clear language (Dorney 1988). |

| In 1977, the Commission on Paperwork issued a report strongly recommending that the government rewrite documents into language and formats that consumers could understand (Redish 1985, 129). | |

| Congress also passed several laws that required warranties, leases, and banking transfers to be clear and readable. These included the Magnuson-Moss Warranty-Federal Trade Commission Act of 1973, the Consumer Leasing Act of 1976, and the Electronic Fund Transfer Act of 1978 (Greer 2012, 5). | |

| President Jimmy Carter issued executive orders requiring plain language in 1978 and 1979. Executive Order 12044 set up a regulatory reform program that required major regulations to be written in plain English so that constituents could comply with them. Executive Order 12174 required agencies to use only necessary forms, to make the forms as short and simple as possible, and to budget the time required to process paperwork annually. President Carter also signed the Paperwork Reduction Act, which took effect after he left office (Redish 1985, 129). | |

| President Ronald Reagan rescinded Carter’s orders requiring plain language. Reagan did, however, support regulatory reform and the Paperwork Reduction Act (Redish 1985, 129–30). Reagan’s secretary of commerce, Malcolm Baldridge, argued for using plain language in business and industry (Bowen, Duffy, and Steinberg 1991). | |

| State of New York | In 1975, Citibank shocked the financial community by dramatically simplifying a loan document. The original loan note had about 3,000 words, but the revised note had 600 (Redish 1985, 130). |

| In 1977, New York became the first state to enact a law requiring plain language. Named the Sullivan Law for its sponsor, Assemblyman Peter Sullivan, it requires businesses (including individual landlords) to write contracts with consumers using words with common, everyday meanings (Felsenfeld 1991). | |

| At least ten other states later followed New York’s lead. Critics predicted a wave of lawsuits over the new contracts, but few filed lawsuits (Kimble 2012, 54–56). | |

| UK Government | The 1974 Consumer Credit Act became the first British law to require plain English. It requires credit-reference agencies to give consumers, upon request, the contents of their files in plain English they can readily understand (Cutts 2009, xvii). |

| In a 1979 protest in Parliament Square, campaigners for plain English publicly shred... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Series Editor Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Understanding Plain Language and Opportunities to Use It

- 2 Overview of Ethics in the Technical and Professional Communication Literature

- 3 Perspectives on Plain Language and Ethics from Professionals around the World

- 4 Profile—Healthwise, Inc.

- 5 Profile—Civic Design

- 6 Profile—Restyling the Federal Rules of Evidence

- 7 Profile—CommonTerms

- 8 Profile—Health Literacy Missouri

- 9 Profile—Kleimann Communication Group and TILA–RESPA Documentation

- 10 Public Examples of Dialogic Communication in Clear Language in the Twenty-First Century

- 11 Conclusion

- References

- Index