![]()

Chapter 1

The Automaticity of Everyday Life

John A. Bargh

New York University

MANIFESTO

If we are to use the methods of science in the field of human affairs, we must assume that behavior is lawful and determined. We must expect to discover that what a man does is the result of specifiable conditions and that once these conditions have been discovered, we can anticipate and to some extent determine his actions. This possibility is offensive to many people. It is opposed to a tradition of long standing which regards man as a free agent, whose behavior is the product, not of specifiable antecedent conditions, but of spontaneous inner changes of course…. If we cannot show what is responsible for a man’s behavior, we say that he himself is responsible for it. The precursors of physical science once followed the same practice, but the wind is no longer blown by Aeolus, nor is the rain cast down by Jupiter Pluvius.

(Skinner, 1953, pp. 6–7, 283)

As Skinner argued so pointedly, the more we know about the situational causes of psychological phenomena, the less need we have for postulating internal conscious mediating processes to explain those phenomena. Now, as the purview of social psychology is precisely to discover those situational causes of thinking, feeling, and acting in the real or implied presence of other people (e.g., Ross & Nisbett, 1991), it is hard to escape the forecast that as knowledge progresses regarding psychological phenomena, there will be less of a role played by free will or conscious choice in accounting for them. In other words, because of social psychology’s natural focus on the situational determinants of thinking, feeling, and doing, it is inevitable that social psychological phenomena will be found to be automatic in nature. That trend has already begun (see Bargh, 1994; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995), and it can do nothing but continue.

Of course, Skinner (e.g., 1978) was incorrect in his position that cognition played no role in the stimulus control of behavior. Even modern animal learning theorists in the Skinnerian tradition (e.g., Rilling, 1992) concluded that as soon as experimental stimuli become more complex and extended over time than the simple static tones and lights used by Skinner, cognitive mechanisms—especially perception and representation—are indispensable for prediction and control of the animal’s behavior. However, as Barsalou (1992) pointed out, the fact that cognitive processes can mediate the effects of situational stimuli on responses does not make those responses any less determined by those stimuli:

Like behaviorists, most cognitive psychologists believe that the fundamental laws of the physical world determine human behavior completely. Whereas behaviorists view control as only existing in the environment, however, cognitive psychologists view it as also existing in cognitive mechanism…. The illusion of free will is simply one more phenomenon in that cognitive psychologists must explain. (p. 91)

In what follows, I argue that much of everyday life—thinking, feeling, and doing—is automatic in that it is driven by current features of the environment (i.e., people, objects, behaviors of others, settings, roles, norms, etc.) as mediated by automatic cognitive processing of those features, without any mediation by conscious choice or reflection.

The Essential Automaticity of Social Psychological Accounts of Human Nature

Theoretical accounts in social psychology have always had a reflexive or automatic flavor, because they lay out the situational factors causing the average person to think–feel–behave in a certain way. Take the following classic examples. For thinking, if your own outcomes will depend on the person you are about to meet, you will spend the extra cognitive effort to learn about him or her as an individual, instead of casually placing him or her into a stock category (Erber & Fiske, 1984). For feeling, if you are in a state of arousal, you tend to interpret your emotional experience in terms of how others in the situation are reacting (Schachter & Singer, 1962). For behaving, if you are told to do something by an authority figure, you tend to do it even if it means lying to another person (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959) or delivering an electric shock to a person who may be having a heart attack in an adjacent room (Milgram, 1963), and if another person needs help you will help if you are the only person around, but not if there are others in the vicinity who could help (Darley & Latené, 1968).

In these several examples of situational influences on cognitive processing, emotional experience, and social behavior, the relation between situational features and the effect of interest can be stated in if–then terms: Given the presence or occurrence of a particular set of situational features (e.g., a person or event), a certain psychological, emotional, or behavioral effect will follow.

The search for specifiable if–then relations between situations and psychological effects also characterizes research on automatic cognitive processes. An automatic mental phenomenon occurs reflexively whenever certain triggering conditions are in place; when those conditions are present, the process runs autonomously, independently of conscious guidance (Anderson, 1992;Bargh, 1989, 1996). Thus, research and theory in both domains, social psychology and automaticity, have, at the core, the specification of if–then relations between situational events and circumstances on the one hand, and cognitive, emotional, and behavioral effects on the other.

The nature of these necessary preconditions (the if side of the equation) can vary. Some require only the presence of the triggering environmental event; it does not matter where the current focus of conscious attention is, what the individual was recently thinking, or what the individual’s current intentions or goals are. In other words, this form of automaticity is completely unconditional in terms of a prepared or receptively tuned cognitive state. These are preconscious automatic processes (Bargh, 1989) and are the major focus of this chapter. They can be contrasted with postconscious and goal dependent forms of automaticity (Bargh, 1989; Bargh & Tota, 1988), which depend on more than the mere presence of environmental objects or events. Postconscious automaticity is commonly studied through the experimental technique of priming. Priming prepares a mental process so that it then occurs given the triggering environmental information—thus, in addition to the presence of those relevant environmental features, postconsciously automatic processes do require recent use or activation and do not occur without it. Goal-dependent automaticity has the precondition of the individual intending to perform the mental function, but given this intention, the processing occurs immediately and autonomously, without any further conscious guidance or deliberation (e.g., as in a well-practiced cognitive procedure or perceptual–motor skill; see Anderson, 1983; Newell & Rosenbloom, 1981; Smith, 1994).

What it means for a psychological process to be automatic, therefore, is that it happens when its set of preconditions are in place without needing any conscious choice to occur, or guidance from that point on. My thesis is that because social psychology, like automaticity theory and research, is also concerned with phenomena that occur whenever certain situational features or factors are in place, social psychological phenomena are essentially automatic. Which of the different varieties of automaticity a given phenomenon corresponds to depends on the nature of the situational (including internal cognitive) preconditions. Some situations may provoke effects without any conscious processing of information whatsoever, and to make the strongest and most conservative case for the automaticity of everyday life, I confine myself in this chapter to evidence of such preconsciously automatic phenomena. But other situations might have their if–then reflexive effects by triggering a certain intent or goal in the individual, resulting in attentional information processing of a certain kind (i.e., an automatic motivation activation; see Bargh, 1990). If the situation activates the same goal in nearly everyone so that it is an effect that generalizes across individuals, and can be produced with random assignment of experimental participants to conditions, the only preconditions for the effect are those situational features.

One might well dispute this conclusion by pointing out the importance of mediating conscious processes and choice for the situational effects in the previous research examples. In the case of the bystander intervention research, for example, the feeling of being less personally responsible to help if others are present (i.e., diffusion of responsibility) is said to mediate the effect of the number of bystanders on the probability of helping (Darley & Latané, 1968). But if these conscious processes do mediate the situational effect, then they must themselves be tied to those situations in an if–then relation for there to be any general effect of the situational variable. This may add extra steps to the if–then causal sequence (i.e., if other possible helpers, then feeling of less personal responsibility and then conscious decision not to help and then no help given). For the effect to occur with regularity across individuals, the feeling of less responsibility and the decision not to help, and so on, are also automatic reactions to the situational information across different individuals.

But where is the evidence for those presumed conscious process mediators of the effect? I confess I did choose the bystander intervention example for a reason; the researchers had no evidence of the theoretical mediator of diffusion of responsibility but instead inferred it from the effect of number of bystanders (Darley & Latané, 1968). The behavioral measure was taken as an indicator of the presence of the cognitive mediator, in other words (see discussion by Zajonc, 1980).

Bystander intervention research is not unique in this regard. Following a review of those studies in which measures were made of behavior and the cognitive processes believed to mediate it, Bem (1972) concluded:

Increase a person’s favorability toward a dull task, and he will work at it more assiduously. Make him think he is angry, and he will act more aggressively. Change his perception of hunger, thirst, or pain, and he should consume more or less food or drink, or endure more or less aversive stimulation. Alter the attribution, according to the theory, and “consistent” overt behavior will follow.

There seems to be only one snag: It appears not to be true. It is not that the behavioral effects sometimes fail to occur as predicted; that kind of negative evidence rarely embarrasses anyone. It is that they occur more easily, more strongly, more reliably, and more persuasively than the attribution changes that are, theoretically, supposed to be mediating them. (p. 50)

Bem continued on to give several examples of studies in which both behavioral and attributional dependent measures were collected, and in which the behavioral measure (e.g., eyelid conditioning, learning performance, pain perception, approaching a feared object) showed clear effects, whereas the measure of the supposed mediating conscious reasoning process showed a weak or absent effect.

Regardless of whether one shares Bem’s conclusions regarding the limited mediational role played by conscious thought processes, the burden of proof has been (unfairly) on models that argue conscious choice is not necessary for an effect. To convince skeptics that effects happen outside of consciousness, or do not require conscious processing to occur, researchers have been made to jump through methodological hoops to establish nonconsciousness beyond any reasonable doubt. It might be a step forward for social psychology to adopt the same level of healthy skepticism for models that include a role for conscious mediation. Where is the evidence that the mediating process exists, and where is the evidence of its mediation of the observed effects? The assumption of conscious mediation should be treated with the same scientific scrutiny as the assumption of automaticity.

The Inevitability of Continued Findings of Automaticity

In developing the argument for the importance of automaticity within all of social psychology, I am contending that social psychology has traditionally focused on situational determinants of behavior, and even within models such as attribution theory that do posit a mediating role for conscious processes as opposed to situational forces alone, there is insufficient evidence to support the position that conscious mediation of situational effects is the rule rather than the exception. Wherever such conscious mediators have been proposed, subsequent research evidence has always constricted their importance and scope.

Note that, as research in areas of social cognition such as attribution, attitudes, and stereotyping progressed since the 1960s, evidence increasingly pointed to the relative automaticity of those phenomena rather than the other way around. Take the case of attribution theory. What were once described in terms of deliberative and sophisticated steps of conscious reasoning (e.g., Kelley, 1967) were found to be “top-of-the-head” (Taylor & Fiske, 1978), heuristic-based (Hansen, 1980), spontaneous (Winter & Uleman, 1984), and finally automatic (e.g., Gilbert, 1989) reactions to the behavior of others. The mediating role of one’s attitudes on one’s behavior moved from being described in terms of a conscious and intentional retrieval of one’s attitude from memory, to a demonstration of automatic attitude activation and influence (Fazio, 1986). The impact of cognitive structures such as stereotypes (e.g., Devine, 1989) and the self (Bargh & Tota, 1988; Strauman & Higgins, 1987) on person perception and emotional reactions were shown to occur without needing involvement of intentional, conscious processing (see Bargh, 1994; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995 for reviews).

The role of conscious choice was diminished even in the realm of selection of an individual’s current processing goal. Social cognition models of the 1980s, for instance, recognized how the outcome of processing was different as a function of the individual’s purpose in processing the information. Yet the “goal-box” in these flow-chart models was presented as an exogenous variable that directed processing, not as an entity that itself was caused by other factors (see, e.g., Smith, 1984; Srull & Wyer, 1986; Wyer & Srull, 1986). However, as researchers uncovered more of the mechanism inside this black box of goal selection (Atkinson & Birch, 1970; Bargh, 1990; Chaiken, Liberman, & Eagly, 1989; Chartrand & Bargh, 1996; Gollwitzer & Moskowitz, 1996; Karniol & Ross, 1996; Martin & Tesser, 1989; Martindale, 1991; Pervin, 1989; Wyer & Srull, 1989), the role presumably played by free will or conscious choice again was diminished—at least the need decreased to invoke the conscious will as a final recourse as it became a superfluous explanatory concept.

So even for social psychological models of the presumed cognitive mediating processes, as research has advanced, so the role of conscious processing has diminished. We have detailed knowledge of the situational features that produce a given phenomenon for most people—a specifiable if–then relation tantamount to an automatic process. But we also have a host of social–cognitive mediating processes such as attributions, trait categorizations, attitudes, stereotypes, and goals, and these mediators are shown increasingly to be equally automatic, if–then reactions to specific situational features.

THE PRECONSCIOUS CREATION OF THE PSYCHOLOGICAL SITUATION

There is historical precedent in theory and recent research evidence that automaticity plays a pervasive role in all aspects of everyday life. Not just in input processes such as perceptual categorization and stereotyping, which have been the principal venue of automaticity research in social psychology (see review in Bargh, 1994); not just in the conscious and intentional execution of perceptual and motor skills, such as driving and typing (see Newell & Rosenbloom, 1981; Bargh, 1996) or social judgment (e.g., Smith, 1989)—but in evaluative and emotional reactions, activation and operation of goals and motivations, and in social behavior itself.

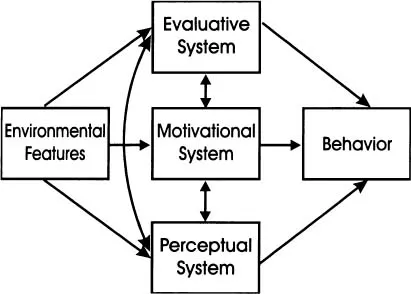

Environmental events directly activate three interactive but distinct psychological systems, corresponding to the historical trinity of thinking, feeling, and doing (see Fig. 1.1). By direct activation is meant preconscious—the strongest form of automaticity (Bargh, 1989). Preconscious processes require only the proximal registration of the stimulus event to occur—the event must be detected by the individual’s sensory apparatus, in other words. Given the mere presence of that triggering event, the process operates and runs to completion without conscious intention or awareness.

FIG. 1.1 Parallel forms of preconscious analysis.

An individual’s cognitive, affective, and motivational reactions to an environmental event combine to constitute the psychological situation for him or her (Koffka, 1925; Lewin, 1935; Mische...