We are faced by a plethora of decisions, choices and judgments every day and throughout our lives: what to have for lunch, where to go on holiday, what car to buy, whom to hire for a new faculty position, whom to marry, and so on. Such examples illustrate the abundance of decisions in our lives and thus the importance of understanding the how and why of decision making. Some of these decisions will have little impact on our lives (e.g. what to have for lunch); others will have long-lasting effects (e.g. whom to marry). To introduce many of the relevant concepts, in this first chapter we consider three important decisions that we might face in the course of our lives: (1) which medical treatment should I choose, (2) is this person guilty or innocent, and (3) how should I invest my money? For each situation we examine some of the factors that can influence the decisions we make. We cover quite a bit of ground in these three examples so don’t worry if the amount of information is rather overwhelming. The aim here is simply to give a taste of the breadth of issues that can affect our decision making. There will be ample opportunity in later chapters to explore many of these issues in more depth.

Which medical treatment should I choose?

Martin and Simon have just received some devastating news: they have both been diagnosed with lung cancer. Fortunately their cancers are still at relatively early stages and should respond to treatment. Martin goes to see his doctor and is given the following information about two alternative therapies – radiation and surgery:

Of 100 people having surgery, on average, 10 will die during treatment, 32 will have died by one year and 66 will have died by five years. Of 100 people having radiation therapy, on average, none will die during treatment, 23 will die by one year and 78 will die by five years.

Simon goes to see his doctor, who is different from Martin’s, and is told the following about the same two therapies:

Of 100 people having surgery, on average, 90 will survive the treatment, 68 will survive for one year and 34 will survive for five years. Of 100 people having radiation therapy, on average, all will survive the treatment, 77 will survive for one year and 22 will survive for five years.

Which treatment do you think Martin will opt for and which one will Simon opt for? If they behave in the same way as patients in a study by McNeil et al. (1982), then Martin will opt for the radiation treatment and Simon will opt for surgery. Why? You have probably noticed that the efficacy of the two treatments is equivalent in the information provided to Martin and Simon. In both cases, radiation therapy has lower long-term survival chances but no risk of dying during treatment, whereas surgery has better long-term prospects but there is a risk of dying on the operating table. The key difference between the two is the way in which the information is presented to the patients. Martin’s doctor presented or framed the information in terms of mortality, namely how many people will die from the two treatments, whereas Simon’s doctor framed the information in terms of how many people will survive. It appears that the risk of dying during treatment looms larger when it is presented in terms of mortality (in the framing adopted by Martin’s doctor) than in terms of survival (in the framing chosen by Simon’s doctor) – making surgery less attractive for Martin but more attractive for Simon.

This simple change in the framing of information can have a large impact on the decisions we make. McNeil et al. (1982) found that across groups of patients, students and doctors, on average radiation therapy was preferred to surgery 42% of the time when the negative mortality frame was used (probability of dying), but only 25% of the time when the positive survival frame (probability of living) was used (see also Tversky & Kahneman, 1981).

Positive versus negative framing is not the only type of framing that can affect decisions about medical treatments. Edwards et al. (2001), in a comprehensive review, identified nine different types of framing including those comparing verbal, numerical and graphical presentation of risk information, manipulations of the base-rate (absolute risk) of treatments, using lay versus medical terminology, and comparing the amount of information (number of factual statements) presented about choices.

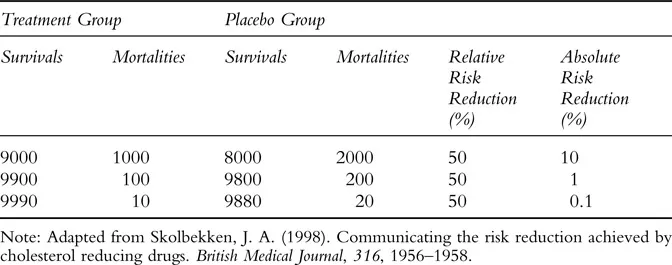

The largest framing effects were evident when relative as opposed to absolute risk information was presented to patients (Edwards et al., 2001). Relative and absolute risks are two ways of conveying information about the efficacy of a treatment, but unlike the previous example they are not logically equivalent. Consider the following two statements adapted from an article about communicating the efficacy of cholesterol-reducing drugs (Skolbekken, 1998; see also Gigerenzer, 2002):

- ‘Savastatin is proven to reduce the risk of coronary mortality by 3.5%.’

- ‘Savastatin is proven to reduce the risk of coronary mortality by 42%.’

A person suffering from high cholesterol would presumably be far more willing to take the drug Savastatin when presented with statement 2 than when presented with statement 1. Moreover, a doctor is more likely to prescribe the drug if presented by a pharmaceutical company with statement 2. But is this willingness well placed?

Implicit in statement 1 is that the risk referred to is the absolute risk reduction – that is, the proportion of patients who die without taking the drug (those who take a placebo) minus the proportion who die having taken the drug (Gigerenzer, 2002). In the study discussed by Skolbekken (1998), the proportion of coronary mortalities for people taking the drug was 5.0% compared to 8.5% of those on a placebo (a reduction of 3.5%). In statement 2 absolute risk has been replaced by relative risk reduction – that is, the absolute risk reduction divided by the proportion of patients who die without taking the drug. Recall that the absolute risk reduction was 3.5% and the proportion of deaths for patients on the placebo was 8.5%, thus the 42% reduction in the statement comes from dividing 3.5 by 8.5.

Table 1.1 provides some simple examples of how the relative risk reduction can remain constant while the absolute risk reduction varies widely. Not surprisingly, several studies have found much higher percentages of patients assenting to treatment when relative as opposed to absolute risk reductions are presented. For example, Hux and Naylor (1995) reported that 88% of patients assented to lipid-lowering therapy when relative risk reduction information was provided, compared with only 42% when absolute risk reduction inform ation was given. Similarly, Malenka et al. (1993) found that 79% of hypothetical patients preferred a treatment presented with relative risk benefits, compared to 21% who chose the absolute risk option. As Edwards et al. (2001) conclude, ‘relative risk information appears much more “persuasive” than the corresponding absolute risk… data’ (p. 74), presumably just because the numbers are larger.

So what is the best way to convey information about medical treatment? Skolbekken (1998) advocates an approach in which one avoids using ‘value laden’ words like risk or chance, and carefully explains the absolute rather than relative risks. Thus for a patient suffering high cholesterol who is considering taking Savastatin, a doctor should tell him or her something like: ‘If 100 people like you are given no treatment for five years, 92 will live and eight will die. Whether you are one of the 92 or one of the eight, I do not know. Then, if 100 people like you take a certain drug every day for five years, 95 will live and five will die. Again, I do not know whether you are one of the 95 or one of the five’ (Skolbekken, 1998, p. 1958). The key question would be whether such a presentation format reduces errors or biases in decision making.

Table 1.1 Examples of absolute and relative risk reduction.

Is this person guilty or innocent?

At some point in your life it is quite likely that you will be called for jury duty. As a member of a jury you will be required to make a decision about the guilt or innocence of a defendant. The way in which juries and the individuals that make up a jury arrive at their decisions has been the topic of much research (e.g. Hastie, 1993). Here we focus on one aspect of this research: the impact of scientific, especially DNA, evidence on jurors’ decisions about the guilt or innocence of defendants.

Faced with DNA evidence in a criminal trial many jurors are inclined to think ‘science does not lie’; these jurors appear to be susceptible to ‘white coat syndrome’, an unquestioning belief in the power of science, which generates misplaced confidence and leads to DNA evidence being regarded as infallible (Goodman-Delahunty & Newell, 2004). Indeed,...