- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jerzy Grotowski

About this book

Master director, teacher, and theorist, Jerzy Grotowski's work extended well beyond the conventional limits of performance. Now revised and reissued, this book combines:

? an overview of Grotowski's life and the distinct phases of his work

? an analysis of his key ideas

? a consideration of his role as director of the renowned Polish Laboratory Theatre

? a series of practical exercises offering an introduction to the principles underlying Grotowski's working methods.

As a first step towards critical understanding, and an initial exploration before going on to further, primary research, Routledge Performance Practitioners offer unbeatable value for today's student.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Biography and Context

A group of excited young South American theatre artists gather at a small airport in the coffee-growing region of Colombia. It is late summer 1970. The brisk mountain air makes them shiver, adding to the tense aura of expectation. These representatives of the International Theatre Festival of Manizales, one of the oldest on the continent, await the arrival of the Festival's honorary president, Jerzy Grotowski.

Grotowski's company, the Polish Laboratory Theatre, is at the height of its fame. Paris, Edinburgh, and New York have sung Grotowski's praises, and the Latin American artists are eager to share in the euphoria of this theatre revolution. Some of them attended performances of The Constant Prince at the Olympic Arts Festival in Mexico City in 1968. Others have seen only photos of the company's groundbreaking productions and of the portly man in dark glasses and black business suit who directs the group. All of them have been warned of Grotowski's severity and his caustic critiques of avant-garde theatre and amateur training methods.

The group shivers again with anticipation and cold as the plane approaches. Upon landing, the door opens, and to everyone's surprise, out steps a thin, bearded wanderer, dressed in flimsy, white cotton, wearing sandals on his bare feet, and carrying a knapsack. Grotowski had transformed himself. As the shocked Colombians run to find him a woolen poncho to protect him from the chill, the theatre world holds its breath.

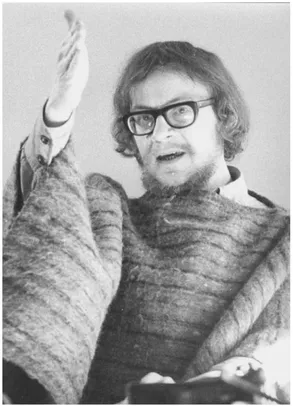

The Enigma

Grotowski (Figure 1.1) was always an enigma. He has been called a master and a charlatan; a guru and a sage; a myth and a monster. Throughout his relatively brief career (he died at the age of 65), Grotowski went through numerous permutations, often catching his critics, and even his friends, off guard.

Figure 1.1 Jerzy Grotowski (1975). Photograph by Mark E. Smith

Spending his childhood under Nazi domination and maturing during the darkest days of Stalinism, he learned at a young age how to use the system in order to seek the best conditions for his work—and always without compromise. He knew that fame was necessary to reach his goals. He knew that fame outside his home country of Poland would be far more beneficial than fame inside Poland. But he also knew that fame was fleeting and that it would be dangerous to succumb to its intoxication.

When the time was right, Grotowski turned his back on fame. He transformed himself. He was able to do this because he always had a plan, a parallel objective to his creative work, a "hidden agenda." This hidden agenda guided many of his choices throughout his career as a stage director and even after he left the arena of public performances.

Grotowski's Formative Years

Jerzy Marian Grotowski was born in the small town of Rzeszow in southeastern Poland on August 11, 1933. His mother, Emilia (1897—1978), was a schoolteacher and his father, Marian (1898—1968), worked as a forest ranger and painter. An older brother, Kazimierz, was born in 1930. When Hitler's Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Grotowski's father escaped to France and then England, fighting as an officer in the Polish army. After the war, Marian Grotowski, a strong anti-Soviet, refused to return to Poland and immigrated to Paraguay. From the age of six, Grotowski never saw his father again. He was nourished by his mother's strength and affection.

When war broke out, Emilia Grotowska moved the family to a small village, Nienadowka, about 12 miles north of Rzeszow. Here they lived meagerly on her teacher's salary. These formative years colored many of Grotowski's perceptions and interests throughout his life. In this tiny village, among peasants, he first confronted tradition, folk beliefs, and ritual, while Grotowski's mother introduced her sons to the spectrum of religious thought.

Early Influences

One day Grotowski's mother brought home Paul Brunton's A Search in Secret India, a curious volume about an English journalist's contact with the mysteries of India. Around the same time, the village priest secretly gave the young Grotowski a copy of the Gospels to read alone. In those years, the Polish Catholic church required the presence and interpretation of a priest to read the Gospels, but Grotowski first encountered Jesus, by himself, in a hayloft above the pigpen of the farm where he lived.

These books—along with Renan's The Life of Jesus—plus The Zohar, The Koran, and the writings of Martin Buber and Fyodor Dostoevsky, served as the foundation for the questions Grotowski pursued during each phase of his creative investigations. But it was Brunton's book that affected Grotowski most profoundly.

Martin Buber (1878-1965): Jewish philosopher, influenced by Jewish mysticism, who believed that one's relation with God could be a direct, personal dialogue. His writings include I and Thou (1923), Gog and Magog (1953), and Tales of the Hasidim (1908).

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-81): Russian novelist. His masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov, includes a parable about "The Grand Inquisitor" who arrests Jesus when he returns to earth. Grotowski included this text in his play Apocalypsis cum figuris.

Through Brunton's writings, Grotowski discovered the teachings of the Hindu mystic Ramana Maharshi (1879—1950). Ramana Maharshi believed that a deep investigation of the question "Who-am-I?" would cause the socialized, ego-oriented, limited "I" to disappear and reveal one's true, undivided being. When pilgrims asked Ramana Maharshi to clarify the meaning of life, the wise man would respond with the statement: "Ask yourself who-am-I." The young Grotowski reacted strongly to these ideas and his pursuit of the question, Who-am-I? developed into one of the chief threads of his life and work.

Already at the age of 10, people with a special kind of wisdom, like Ramana Maharshi, fascinated Grotowski. Later in life, he called such people by the Russian word yurodiviy, "holy fool," and he dedicated one aspect of his investigation to making contact with such yurodiviy, directly. Actual transmission of knowledge, whether received or stolen, through real confrontation with a master, became a special field of interest for Grotowski. In fact, transmission became the main thrust of the last period of his work and defined his relationship with Thomas Richards (b. 1962), an American actor who, since Grotowski's death, directs his research center in Pontedera, Italy.

Theatre School

In 1950, Grotowski's family moved to Krakow where he finished his secondary studies. He had missed a year of school due to illness, the beginning of serious health problems that would plague Grotowski throughout his life. Undecided as to which discipline he should choose for a career, Grotowski sent out three applications for advanced study: one to the medical school for psychiatry; one to the program in Oriental Studies; and, finally, one to the Acting Department of the State Theatre School in Krakow. The Theatre School was the first to respond and Grotowski's destiny was determined.

On the entrance exam he received only "satisfactory" grades for his practical work, including an "F" for diction. However, his essay on the topic, "How can theatre contribute to the development of socialism in Poland?" received an "A" and he was accepted into the program on probation.

Grotowski often said that theatre studies appealed to him because, although performances themselves operated under strict censure by the Polish government, rehearsals were unregulated. He believed that the rehearsal process might provide a fertile field to seek answers to his questions.

While in theatre school, Grotowski continued to develop his interest in Asia. He studied Sanskrit and met with specialists. He also published several articles forming the basis for his future theatre pronouncements: one article included a call for more government support of young theatre artists; another article envisioned a "theatre of grand emotions," in which action is structured consciously and real-life details are used only when "absolutely necessary to evoke the emotions or to clarify the action ..." (cited in Osiński 1986: 17).

Upon graduation with an actor's certificate in June 1955, Grotowski was assigned to the Stary Theatre of Krakow. His contract was delayed, however, when he received a scholarship to study directing at the State Institute of Theatre Arts (GITIS) in Moscow.

The Russian Connection

When Grotowski left for Moscow in August 1955, he was known as a "fanatic disciple of Stanislavsky" (Osiński 1986: 17; emphasis mine). Stanislavsky's system was the "official" curriculum of the Polish theatre school, but most students regarded the Russian's contributions to actor training with disdain. Grotowski, however, saw the seeds of truth in Stanislavsky's system of physical actions, and he went to Moscow to study the system at its source.

Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavsky (1863-1938): established the Moscow Art Theatre with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko (1858-1943) in 1898. The system of physical actions, one of his final innovations, highlights doing rather than emotion as the actor's fundamental tool.

During his year at GITIS, Grotowski studied with Yuri Zavadsky (1894— 1977). Zavadsky, an actor who had performed under Stanislavsky and Evgeny Vakhtangov, now directed theatre productions that followed the strict socialist-realistic style. Zavadsky observed that Grotowski instinctively worked with actors in a manner similar to Stanislavsky himself. One day Grotowski visited Zavadsky's apartment. The teacher showed the student his awards, his passport (unusual under Soviet socialism), and the two limousines and chauffeurs at his disposal. Zavadsky whispered, "I have lived through dreadful times and they have broken me. Remember, Jerzy: nie warto, it is not worth it. This is the harvest of compromise" (cited in Barba 1999: 24). Years later Grotowski revealed that this episode touched him deeply and gave him the strength to resist the pressures of compromise during his years of working under an oppressive political system. Grotowski considered Zavadsky as one of his great masters (Barba 1999: 24—5).

Evgeny Vakhtangov (1883-1922): student of Stanislavsky who directed the Moscow Art Theatre's First Studio and developed his own creative style of production called "fantastic realism." Grotowski was especially influenced by his playful production of Turandot (1922).

Socialist-realism: was the predominant art form in the Soviet Union under the rule of Joseph Stalin (1879-1953). Its goals were to realistically and heroically depict the aspects of revolution and the common worker's life in an optimistic fashion, while educating the public in the principles of communism.

In Moscow, Grotowski also discovered the theatre experiments of Stanislavsky's protégé, Vsevelod Meyerhold (1874—1940). Meyerhold's innovative staging techniques, actor-training methods, and dramaturgy led him into direct confrontation with the Soviet authorities. In 1939, he was imprisoned and then executed for his refusal to submit to the artistic homogeneity required during Stalin's regime. Meyerhold's name and contributions were erased from historical records and he had yet to be "rehabilitated" by the post-Stalin authorities during Grotowski's stay in Moscow. The curious Polish director, with the aid of a kindly librarian, would sneak into a locked section of the library after-hours and pore over the forbidden documents describing Meyerhold's groundbreaking theatre work. Grotowski said that from Stanislavsky he learned how to work with actors, but it was from Meyerhold that he discovered the creative possibilities of the stage director's craft.

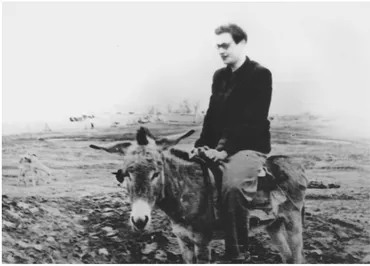

First Travels

Upon completion of his one year of studies in Moscow, with his health in a precarious state, Grotowski embarked on a two-month trip to Central Asia (Figure 1.2). This trip, his first direct encounter with the East, further stimulated his interests in Asian philosophy and the practical aspects of Asian traditional and classic performing arts. He often spoke of a special meeting with one of the holy fools (yurodiviy) that occurred on this trip: "I met an old Afghan named Abdullah who performed for me a pantomime 'of the whole world', which had been a tradition in his family" (cited in Osiński 1986: 18). Grotowski saw his own questions embodied in the gestures of the old man: could the actor incarnate the whole world, nature itself? And could nature itself, with all its unpredictability, uniqueness, and constancy, reveal itself in the actor? Throughout his career, Grotowski showed little interest in actors who behave "naturally" on stage. Instead he sought those actors who reveal nature—their own personal nature as well as that of all humanity. Eventually, he would call this phenomenon organicity, one of the enduring searches of Grotowski's career.

Figure 1.2 Jerzy Grotowski in oasis Kara-kum (1956). Photographer unknown, courtesy of the Archive of the Grotowski Centre, Wroclaw

The Political Game

When he returned to Poland in autumn 1956, Grotowski found the country embroiled in workers' riots.These protests, supported by many intellectuals and artists, came to be known as the Polish October and Grotowski, for the only time in his life, actively and publicly worked in a political forum. He became a leader of the youth movement calling for reforms and published several provocative articles. His activity stopped abruptly, however, in early 1957. It's possible the decision to halt his political activity was made under a certain amount of pressure, and even threats, from the authorities. Eighteen years later, when he spoke about th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface to the reissued edition

- Acknowledgments

- 1 BIOGRAPHY AND CONTEXT

- 2 GROTOWSKI'S KEY WRITINGS

- 3 GROTOWSKI AS DIRECTOR

- 4 PRACTICAL EXERCISES

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Jerzy Grotowski by James Slowiak,Jairo Cuesta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.