eBook - ePub

Sharing Nature's Interest

Ecological Footprints as an Indicator of Sustainability

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sharing Nature's Interest

Ecological Footprints as an Indicator of Sustainability

About this book

Ecological footprinting is rapidly being adopted as an effective and practical way to measure our impact on the environment - in both large- and small-scale planning and development. This is an introduction to ecological footprint analysis, showing how it can be done, and how to measure the footprints of activities, lifestyles, organizations and regions. Case studies illustrate its effectiveness at national, organizational, individual and product levels.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sharing Nature's Interest by Nicky Chambers,Craig Simmons,Mathis Wackernagel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Redefining Progress

‘Progress means getting nearer the place you want to be. And if you take a wrong turning, then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about face and walking back to the right road, and in that case the man who turns back the soonest is the most progressive man’ (C S Lewis in ‘Mere Christianity’)1

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

What will the world be like in 2050? By that time the human race will have had to face up to many environmental and social barriers to real progress. To take just a few examples:

• How can we feed a global population predicted to be half as big again as at the turn of this century?

• Can we succeed in eliminating poverty and inequality whilst providing an acceptable quality of life for all?

• Will we be able to harness enough energy to power our economies without damaging environmental consequences?

• Can we halt the decline in biodiversity and learn to live in harmony with other species?

These are just some of the big questions that society has only recently begun to address under the umbrella term of ‘sustainable development’.

In 1987 the Brundtland report Our Common Future popularized the use of this phrase, defining it as, ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. Former UK Environment Minister John Gummer put it more succinctly when he said that sustainable development amounts to ‘not cheating on our children’.

Box 1.1 Some Further Attempts at Defining Sustainable Development

Friends of the Earth: ‘Meeting the twin needs of protecting the environment and alleviating poverty’2

UK Government: Social progress which recognizes the needs of everyone, effective protection of the environment, prudent use of natural resources, maintenance of high and stable levels of economic growth and employment.3

Sir Crispin Tickell: Sustainable Development is ‘treating the earth as if we meant to stay’4

The Body Shop: ‘Sustainability and sustainable development remain elusive concepts. They have variously been referred to as, for instance, “vision expression”, “value change”, “moral development”, “social reorganization”, or “transformational process”’.5

Steve Goldfinger (on ecological sustainability): ‘Turn resources into junk no faster than nature can turn junk back into resources’.6

See also Pearce, D, Markandya, A, and Barbier, E, 1989, Blueprint for a Green Economy, Earthscan, London.

There are many other equally valid definitions (for examples see Boxes 1.1 and 1.2). Despite the number and variety of definitions, there are certain common principles that have gained widespread acceptance:

• Human quality of life ultimately depends on, amongst other things, a healthy and productive environment to provide both goods and services and a pleasant place to live.

• The needs of the poor must be met, providing at least a basic quality of life for all of the world’s population.

• Future generations should have the same opportunity to harness the world’s resources as the current generation.

The maintenance of human well-being relies on the provision of goods and services. That is not to say that all things that enrich our lives depend on material consumption, merely that many do. We need energy for heat and mobility, wood for housing, furniture and paper products, fibres for clothing, and food and water to sustain us.

These in turn rely on an intricate web of natural processes to maintain the quality of the air, fertility of the soil, fresh water and more besides. We all depend on nature both to supply us with resources and absorb our waste.

But, to paraphrase the title of Al Gore’s book, the earth is in balance.7 Living beyond our ecological means will surely lead to the degradation of our only home; human well-being will suffer.

Similarly, having insufficient natural resources and living in unsatisfactory and inequitable ways will cause conflict and degrade our social fabric.

To make sustainability happen, we need to balance the basic conflict between the two competing goals of ensuring a quality of life and living within the limits of nature. Humanity must resolve the tension between ultimate ends (a good life for everybody) and ultimate means (the capacity of the biosphere).8

In this context, one of the most helpful and practical definitions of sustainable development is ‘improving the quality of life while living within the carrying capacity of supporting ecosystems’.9

Finding ways to meet this challenge is the focus of this book. Let us start with a closer look at what is meant by sustainability, consumption and quality of life.

SUSTAINABILITY, CONSUMPTION AND QUALITY OF LIFE

The Collins Dictionary definition of consume is ‘v. to destroy or use up’ and consumption ‘expenditure on goods and services for final personal use’.

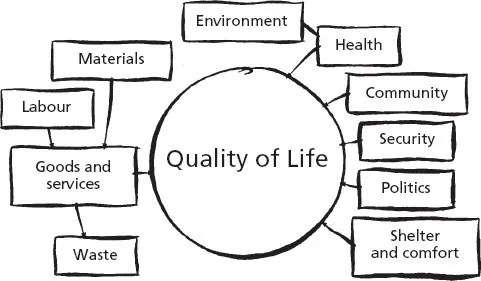

Many aspects of human quality of life are a function of consumption (see Figure 1.1). Those goods and services which sustain us, and make our lives easier or more pleasant, all require inputs of materials and usage of natural sinks for waste products. From the economist’s viewpoint, Paul Ekins has said ‘what is destroyed by consumption is the value (from the human point of view) that was added in production’.11

Box 1.2 Six S’s to Save the World!

Do you remember the three R’s of education: reading, writing and arithmetic? Now it is time to learn about the six S’s of sustainability.

• Scale The scale of the human economy must not exceed the capacity of the biosphere.

• Solar The power source of the future is the sun. Most human processes will need to be powered directly (or indirectly) by solar energy.

• Cyclic (or ‘S’yclic?) If we do not reuse materials and recycle our wastes – mimicking the cyclical processes of nature – then we will deplete our resources and accumulate pollution.

• Shared A core principle of sustainability is that of equity. Nature’s wealth should be shared rather than hoarded or appropriated by a minority.

• Safe No activity should compromise the health of plant or animal species, including people, by increasing the level of toxicity in the environment.

• Sexy No one wants to live in a world without fun!

With thanks to Edwin Datschefski, Biothinking International.10

The value or ‘quality of life’ we gain from consumption depends on a number of factors such as the sorts of activity we do (playing a game of cards is obviously less resource intensive than an outing in the car) and how efficient we are at converting materials into goods and services – one car might be more energy-efficient than another.

There is convincing evidence that above a certain threshold, further consumption adds little to reported quality of life.12 For example, the percentage of Americans calling themselves ‘happy’ peaked in 1957 – even though consumption has more than doubled in the meantime.13

The cumulative environmental impact of any activity can be considered as a function of consumption levels. Where consumption patterns exceed nature’s carrying capacity, locally or globally, then this is – by definition – unsustainable. In considering the impact of human consumption we need to be aware of both the number of consumers and the resource use associated with each activity.

Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren proposed the IPAT model where:14

Impact = Population × Affluence × Technology

This clearly shows the relationship between environmental impact, the number of consumers, the affluence – or level of consumption – of each consumer and the technological efficiency in delivering a particular product or service (see Box 1.3). We can simplify the model even further by considering consumption as the product of affluence and technology:

Impact = Population × Consumption

where consumption is the product of the efficiency with which the lifestyle activity is delivered. For example, the amount of fuel used to travel a certain distance depends on both the mode of transport and the efficiency of that form of travel.

To achieve ecological sustainability at a global level, ‘impact’ needs to be within the natural limits imposed by planetary carrying capacity. We consider this in greater detail in Chapters 3 and 4. For social sustainability, consumption patterns need to deliver at least a minimum quality of life for all.

Figure 1.1 Many aspects, though not all, of human quality of life are a function of consumption

LINKING ECONOMICS, QUALITY OF LIFE AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Achieving sustainable development relies not only on the successful integration of social – quality of life – and environmental policies, but also on economic factors. How these so-called three ‘pillars’ fit together is the key. All too often we see the economy being treated as the sole ‘bottom line’ priority, in the mistaken belief that society and the environment exist to serve the economy rather than the other way around (see Figure 1.2a).

There is clearly a balance to be struck between the three elements. The phrase ‘triple bottom line’ is ‘now embedded in the corporate lexicon world-wide’.15,16 It is patently true that commerce cannot exist outside society, and society cannot exist outs...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Figures, Tables and Boxes

- Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Redefining progress

- 2 Indicating progress

- 3 Footprinting foundations

- 4 Footprinting fundamentals

- 5 From activities to impacts

- 6 Twenty questions about ecological footprinting

- 7 Global and national footprints

- 8 Regional footprinting

- 9 Assessing the impact of organizations and services

- 10 Footprinting for product assessment

- 11 Footprinting lifestyles – how big is your ecological garden?

- 12 Next steps

- Annexe 1 – A Primer on Thermodynamics

- Conversion Tables

- Glossary

- Index