- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Science-Based Dating in Archaeology

About this book

Archaeologists and archaeology students have long since needed an authoritative account of the techniques now available to them, designed to be understood by non-scientists. This book fills the gap and it offers a two-tier approach to the subject. The main text is a coherent introduction to the whole field of science-based dating, written in plain langauge for non-scientists. Additional end-notes, however, offer a a more technical understanding, and cater for those who have a scientific and mathematical background.

Information

1 Generalities

1.1 THE IMPACT OF SCIENTIFIC TECHNIQUES

A fragment of Bronze Age pottery found in Greece will be dated by matching its form and decoration to a phase of the ceramic chronology established for the region. The basic framework to which that chronology is related – by archaeological cross-linkages – is the Egyptian calendar. This begins around 3000 BC, at the start of the First Dynasty, and it is fixed in calendar years through the recorded observation, more than 1000 years later, of a datable astronomical event1 in the ninth year of the reign of Sesostris III; this recording ties down the floating chronology provided by fragmentary lists of kings and their reign lengths. On account of the astronomical anchoring the framework is essentially science-based, but the usual meaning of scientific techniques is exemplified by radiocarbon dating which from the early 1950s provided a time-scale extending into the Neolithic and beyond; the impact was dramatic, upsetting previous conjectures about the pace of man’s development – what had been thought to have taken man one or two millennia to achieve was now seen to have taken four or five. Far beyond the Neolithic in the early stages of hominid development more than a million years ago it is potassium–argon dating that provides the time-scale and allows a proper understanding of the origins of early modern man to be developed. The stages by which Homo sapiens sapiens emerged from his forebears, and particularly the role of the Neanderthal branch, are increasingly datable by a number of other techniques, filling what used to be the gap between potassium-argon and radiocarbon – recent technical developments in the former are closing it anyway.

Subsequent to 3000 BC there has been impact too. For regions more remote from Egypt than Greece chronological schemes had been developed on the hypothesis that there would have been diffusion of technical and cultural developments outwards from the Near East towards western Europe. Here too radiocarbon (when calibrated) stimulated a reappraisal, showing the hypothesis to be untenable and that independent invention had occurred. Thus scientific dating is not just a boring necessity that tidies things up by providing numbers, it is vital for valid interpretation.

1.2 ABSOLUTE DATING AND DERIVATIVE DATING

There is a tendency to regard all scientific techniques as being ‘absolute’. The proper meaning of absolute dating is that it is independent of any other chronology or dating technique, that it is based only on currently measurable quantities. Most of the techniques discussed in this book are indeed absolute, but not all, e.g. archaeomagnetic dating requires a reference curve having a time-scale provided by archaeological or other chronology. Radiocarbon is absolute only to within limits; for high accuracy, calibration by means of tree-ring dating (dendrochronology) is required. Some techniques can be applied in either absolute or derivative mode, e.g. amino acid dating and obsidian hydration dating.

1.3 THE EVENT BEING DATED

An obvious requirement in a dating technique is that there is a measurable time-dependent quantity that forms the ‘clock’. It is also necessary that there must be an event that starts the clock and that this event must be relatable to the archaeology of interest. Some techniques automatically relate to the archaeology, e.g. the thermoluminescence clock in pottery is set to zero by ancient man’s firing of a kiln. In others the association may only be approximate, e.g. the radiocarbon clock in wood starts when the wood forms, not when the tree was felled nor when man utilized it; hence the emphasis on ‘short-lived’ samples such as grain and twigs.

1.4 REASONS FOR DATING

Scientific dating is expensive,2 both in equipment and personal effort; it may also be destructive of highly prized archaeological material. Therefore the archaeological questions that will be answered need to be carefully considered before the process is set in motion. It also needs to be established that the likely error limits are good enough; although this book attempts to give indication of these for the various techniques, direct discussion with the dating laboratory enables the likely performance of the technique on the site concerned to be properly assessed.

There is a hierarchy of reasons for dating. At the top there are dates which have world-wide significance, e.g. the relationship of early modern man to Neanderthal Man. Then there are dates that establish or strengthen the basic chronological framework of a region. Another reason is the need to date a site when there is doubt about its relationship to the region’s chronological framework. Finally there may be the need to test a new technique or to assess the performance of an established one in particular circumstances.

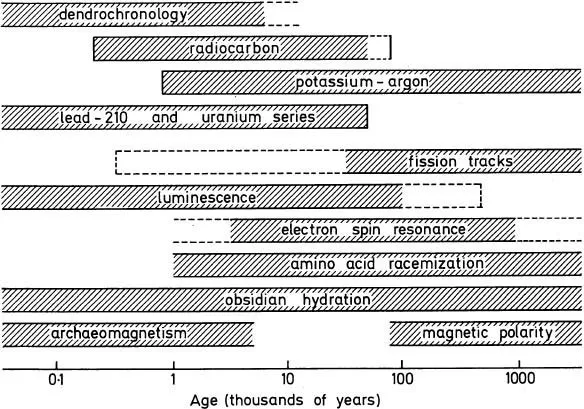

Fig. 1.1 Applicability chart. Given a closed circle and an appropriate age range there are good prospects of a reliable date; less than closed circles indicate there are qualifications to be made, perhaps about reliability or perhaps about limitations in applicability. The chart is comparative in either direction; it is intended as a guide to further reading rather than a definitive judgement.

1.5 WHICH TECHNIQUE?

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 provide overviews which may be useful to archaeologists in considering which techniques might be useful on their various sites. Inevitably there are many qualifications in regard to applicability, and having read the appropriate chapter the archaeologist should consult a relevant laboratory for assessment of likely error limits and reliability in the particular circumstances concerned; essential data in this assessment are the state of preservation of the available samples and the precision of the association between the event which the technique would date and the event of archaeological significance.

1.6 DATING TERMINOLOGY

The pre-eminent technique, radiocarbon, produces an age in ‘radiocarbon years’ and these are not quite the same as calendar years; conversion to the latter requires reference to a calibration curve, as discussed in section 4.4. In general the other techniques produce an age directly in calendar years (though often with error limits that encompass the difference between radiocarbon age and calendar age).

Fig. 1.2 Age ranges of techniques. Actual limits are dependent on circumstances, e.g. state of sample preservation; also, they are liable to widen with continued technical development.

To avoid continued confusion the 1985 International Radiocarbon Conference at Trondheim recommended the use of cal AD, cal BC, and cal BP for calibrated dates and ages; BP means ‘years before present’, the latter being defined as AD 1950. Omission of ‘cal’ implies use of radiocarbon years.

While this convention may deal with the problem as far as radiocarbon is concerned there is the difficulty that for other techniques AD, BC and BP imply calendar years, a usage established for the two former over many centuries. In this book the traditional meaning is retained for AD and BC, i.e. calendar years with respect to the birth of Christ; BP means ‘radiocarbon years before AD 1950’ as recommended at the conference, though it is used sparingly, substitution of ‘radiocarbon age’ usually being made; simple ‘years ago’ implies calendar years before the date of determination. A convention adopted by the journal Antiquity is the use of ad, bc and bp for uncalibrated dates and ages, and corresponding capital letters after calibration. Though highly convenient it has not been generally adopted, its use being restricted mainly to Britain; it has not been followed in this book.

Although used sparingly in this book, common terminologies for ‘thousand years’ are kiloyear (kyr) and kiloan (ka), the latter being French; similarly Myr and Ma for million years.

NOTES

1. The event was the heliacal rising of the bright star Sothis (Sirius). This star rises during daylight for a major portion of the year but its rising gets progressively earlier; hence there comes a day on which it is just enough in advance to be visible. Because there were only 365 days in the Egyptian calendar and no adjustment for leap year, the event moved forward by 1 day every 4 years, completing a full Sothic cycle in 1453 years. The cycle is tied into the Christian calendar by the recording in AD 139 of a heliacal rising on New Year’s Day in the Egyptian calendar. The recording of a heliacal rising on the sixteenth day of the eighth month of the seventh year of Sesostris III allows dating of that day to 1870 (±6) BC. Historical records are complete enough to give Egyptian history a firmly based chronology back to 2000 BC. Earlier than this the chronology is extrapolated by means of the Turin canon and the incomplete fragments of the Palermo stone. Most interpretations place the start of the First Dynasty within a century of 3000 BC.

Other regions, e.g. Mesopotamia, have astronomically based calendars too, though none reaching earlier than 3000 BC. The Mayan calendar of the Aztecs is another example.

2. A major part of science-based dating is carried out through collaborative programmes between laboratories and archaeologists, funded by national research councils. As a direct service, laboratories are increasingly under obligation to recover the full cost and the following current estimates, in US dollars, give a rough guide as to what to expect: radiocarbon, 200–600; uranium series, 700–1500; thermoluminescence date, 100–500; thermoluminscence authenticity test, 250; obsidian hydration, 25–500. Addresses of laboratories that provide a service are usually obtainable from national archaeology associations, etc.

2 Climatic clocks and frameworks

2.1 INTRODUCTION

In the present chapter we outline some climate-based approaches to dating which, with one notable exception, evolved essentially from visual observation of archaeological/geological material; these are in contrast to the main content of the book which is concerned with laboratory-derived techniques which were taken into the field. We may regard the former as natural ways of dating in the sense that observation of the changing seasons and the motions of sun, moon and stars are natural ways of telling the time as opposed to using intricate technical devices known as clocks.

Particularly for Palaeolithic archaeology, climatic variation provides a chronological framework; it is the task of more quantitative techniques to provide absolute dates for this framework. For more recent archaeology it is the annual growth rings of a tree and the annual layers in sediment from melting glaciers that are relevant and in themselves precisely quantitative; these annual clocks have been of critical importance in providing absolute calibration of the radiocarbon time-scale.

In outlining the dating connotations of climatic change we are seeing only the tip of the iceberg of the much larger topic of palaeoclimate reconstruction. For the latter the reader should consult other texts such as those by Lowe and Walker (1984) and by Bradley (1985).

2.2 CLIMATE-BASED FRAMEWORKS

Successive glaciations and deglaciations define a period of recent geological time known as the Quaternary (roughly the last 2 million years). The Pleistocene is the first epoch of the Quaternary and this follows the Pliocene, the last epoch of the Tertiary period. The beginning of the Pleistocene is i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Generalities

- 2 Climatic clocks and frameworks

- 3 Radiocarbon – I

- 4 Radiocarbon – II

- 5 Potassium–argon; uranium series; fission tracks

- 6 Luminescence dating

- 7 Electron spin resonance

- 8 Amino acid racemization; obsidian hydration; other chemical methods

- 9 Magnetic dating and magnetostratigraphy

- Appendix: Radioactivity data

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Science-Based Dating in Archaeology by M.J. Aitken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.