A prodigious variety

Selinunte, Sicily, on a hot, hot day. A Greek temple composed of enormous blocks stands four-square on its columns. Just beside it – an untidy heap of large chunks of blinding white limestone cut into smooth geometric shapes that fit exactly to each other, face to face. There are no layers of soil: the area resembles the untidy playroom of a giant child. This is the fate of some famous architecture: it partly fell, or was demolished, dispersed and then tidied up, leaving the fragments broken and scattered or gathered into piles. And they are still there (FIG 1.1).

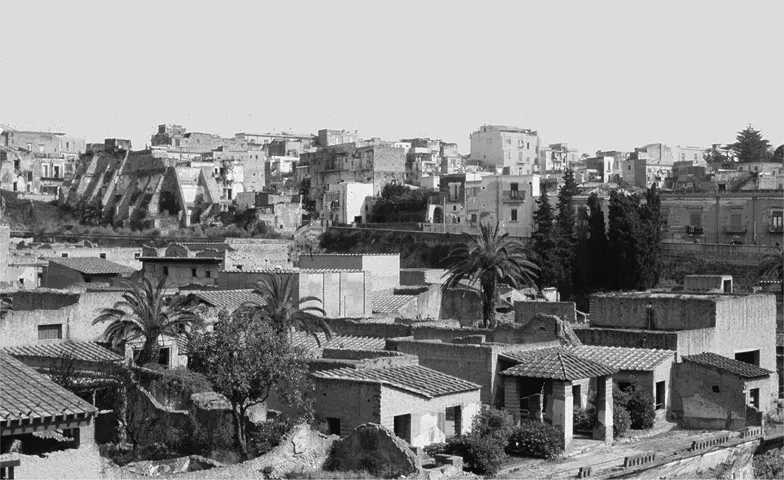

After a short journey north across the Tyrrhenian Sea, we arrive at Vesuvius, the volcano which erupted in AD79, burying the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum (FIG 1.2). Modern-day Ercolano is a mass of apartments stacked on

FIGURES 1.1 Temple into heap: limestone structures at Selinunte, Sicily (P.A. Rahtz and author).

FIGURE 1.2 The Roman town of Herculaneum, buried by volcanic eruption in AD79; and above it the modern town of Ercolano (author).

top of each other with the washing hanging out, overlooking streets full of cars hooting at dodging pedestrians. Ancient Herculaneum lies underneath it, with orderly straight thoroughfares and stepping stones which wagons could trundle over and people could cross. Herculaneum was overwhelmed by volcanic lava one afternoon, while its neighbour, Pompeii, was buried in ash raining from above followed by the white hot avalanche of a pyroclastic surge. Although many people got away, taking their most precious things with them, others were caught and carbonised, together with dogs, vineyards and gardens. Over these cities, the volcanic deposit lies some 10m deep. Excavated for more than two hundred years, archaeologists find mortared brick walls, the orange tiles of collapsed roofs, mosaic pavements rippled by the earth tremors that accompanied the eruption, and the occasional sad charred hollow of a human.

Further north still we can see numerous other kinds of building in the process of finishing their days. A farm shed in Herefordshire, Britain, made from a framework of stout timbers has been patched with planks and corrugated iron (FIG 1.3). After a long and neglected old age, its time is near: the timbers are rotting at the foot and lurch to one side, spilling the tiles off the roof. Soon the shed will turn into a shallow heap; the timbers will be eaten up by bugs and the iron sheets disappear into a rusty powder. What remains on the surface will be cleared away, leaving beneath it a curious imprint in the earth: long dark random stripes of rotten wood with broken sherds of tile and orange patches of decayed iron.

FIGURE 1.3 Timber-frame barn, on the way out, near Bromyard, Herefordshire (photo: P.A. Rahtz).

While the building totters, various agents like to help it on its way: people can always spot a ruin and love to fiddle with it. An Anglo-Saxon church that was falling down at Moreton on the Hill in Norfolk provided an intriguing stage set for these final years of a redundant building. Ivy and creeper encircled its round tower, slowly pulling it down by inserting tendrils and gouging out the soft mortar. Rats and mice widened every hole. Birds flew in and out of the roof-space and nested there. Inside, the ceiling was splitting and dropping down on the floor in slabs of plaster. The first plants were gaining a purchase in the cracks in the floor and in the wet patch inside the baptismal font. And someone had been attracted to this deserted romantic hideaway – possibly the homeless, but more likely the very young: no-one can modify a space as thoroughly as children building a den. Here they had pushed the pews against the north wall and lifted the font cover with its big iron spike and placed it at the east end where the altar was. Then they placed the chairs around the spike in a semi-circle. This is not how a church was used of course, and if the picture froze like this and sank back in this configuration into the earth, future archaeologists would deduce that they had found the ritual centre of a coven of spike worshippers.

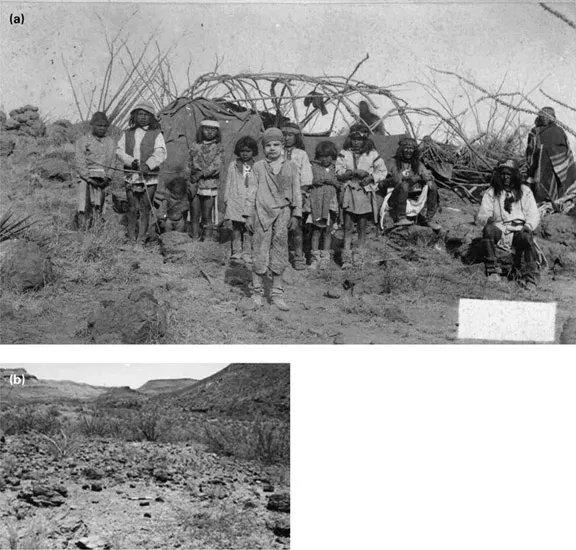

Some human sites, each with its own contemporary drama, leave next to nothing on the ground. FIGURE 1.4 shows an example from Mexico, a photograph taken in 1886 of one of Geronimo’s last camps before his surrender at Los Embudos. This wickiup

FIGURES 1.4 Geronimo’s wickiup (a), and prehistoric stances left by shelters of the kind in the same terrain (b) (Arizona Historical Society).

was a shelter formed among rocky boulders out of branches and cloth. When such places are later dispersed by wind and scavengers there is nothing much left but a little oval clearing among the stones – or, if it got burnt down, a round patch of ash and partly burnt wood, like a bonfire, miles from anywhere. These ephemeral traces provide a poignant analogue for many millions of barely detectable dwellings built in the course of eventful lives throughout prehistory.

What archaeologists encounter in the ground is the end product of stories like this, stories of loss, decay and abandon. We will meet many examples in this book, but the colour plates offer a taster of their prodigious variety. Underneath the topsoil of a ploughed field, the doings of earlier people show as sets of spots and stripes (Colour Plate 1a). In well-frequented places, the debris builds up and lies deep, layer on layer (Colour Plate 1b). Modern instruments, like aerial cameras or radar, can sometimes sense these things before you see them (Colour Plate 2), but they become clearer when the soil comes off. Underground, while most structures are wispy traces, others are still robust – with mortared walls and mosaic floors (Colour Plate 7). Like buildings, our mortal remains also survive in very variable forms (Colour Plates 6a–c). Some, like the inhabitants of Pompeii, are now just a void in the baked volcanic ash. In the bog bodies of northern Europe acid has eaten out all the bones, but the flesh is preserved, tanned like a great leather bag. In Egypt and Mongolia, bodies were wrapped up in cloth by their burial parties, and survive as mummies, fibrous and desiccated. For people buried on chalky soils, the flesh quickly goes, but the bones survive clean and sharp – a white skeleton. On sandy acid soils, the bones disappear but the flesh may leave its signature on the grave floor – a stain or a rounded sand-shape. The ingenuity of the modern excavator can conjure up a striking image from the most ephemeral of traces: as an example I show a leather chariot in a Chinese tomb, evoked in three dimensions from the surviving film of paint that once covered the now vanished timbers (Colour Plates 8a–c).

Archaeological investigation starts here, with the pieces of the past, life’s disjecta membra, the stuff. This is what we study. Making sense of this structured dirt, this materiality, is what gives us our mission, and our first task is to appreciate why we have what we have. All these cultural remains belong to people who deserve a history, but they do not equally leave us one. Some build to last, others build for the moment. Some seek immortality by wrapping up mummies and placing them in enormous tombs, others throw bodies deliberately or carelessly into bogs, or into holes in the ground. Other people die in accidents, never to be found or commemorated. Some take a lot of trouble to defeat time, and others do not. The survival of things is also clearly dependent on the type of soil in which things are buried. Chalk – well-drained and alkaline – is kind to bone; sand, well-drained and acid, is not. Anaerobic conditions, i.e. deposits that exclude air, like a bog, inhibit microbes so that organic materials are preserved. But the acid still dissolves the minerals, like the calcium salts of which bone is made. Under the ground, things are never alone for long. Humic soil is a mass of busy micro-organisms, digesting everything. Worms swallow the soil and spit it out, over and over again. Their tireless mixing raises the ground surface, until it climbs over the great flat stones of megaliths, buries Roman mosaics, creeps up the sides of stone crosses and over the steps of medieval churches. Beetles, rats and dogs like to dig and rummage in bodies. Pillagers dig them up to take the grave goods. Farmers plough the graves, rubbing down the first 25cm and mixing it up with the ploughsoil. Even when archaeological sites are deserted, they do not entirely die. They have a long and varied afterlife in which plants, animals and humans – archaeologists eventually among them – will intervene.

Methods of study

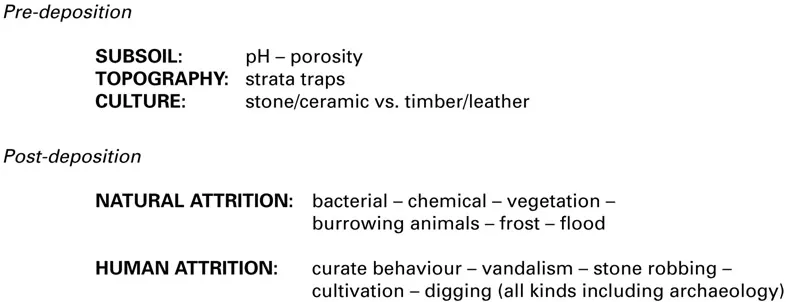

The archaeologist Michael Schiffer has made a comprehensive study of the factors that affect the creation of sites, factors which he called “Site Formation Processes”, dividing them into natural and cultural agents, and distinguishing between the “systemic context”–the site when occupied, and the “archaeological context” – the site when buried and then rediscovered by us. The archaeological task is to use the one to read the other and deduce how the “transforms” occurred. It is handy to have a list of the factors that do the transforming (FIG 1.5) and to imagine the various stages that the site passes through as it gets buried (FIG 1.6). Here I propose five stages for this hypothetical journey: (1) before anything happens, (2) during occupation, (3) at abandonment, (4) when the site gets buried, and (5) after that. This model is not so much a straight transformation from one state to another, as a continuous itinerary of decay, suffered by all sites everywhere, in which at a given moment archaeologists may intervene with their trowels and shovels. This “intervention” may occur at any stage: we meet the oldest sites when they are well buried; but more recent sites may be examined just after they are abandoned, and some operations, like the recording of lived-in buildings, are carried out while the patient, so to speak, is still conscious. After a site has been visited by an archaeologist, it continues to deteriorate towards an ultimate state of nothing, unless actively prevented – the task of conservation. Every site in the world is therefore on the move to oblivion, fast or slow dependent on the measures we are able to apply. This management of our archaeological resources is the largest single activity in the archaeology business, and provides the context in which we all work. But we are not quite ready to talk about that yet (see Chapter 15).

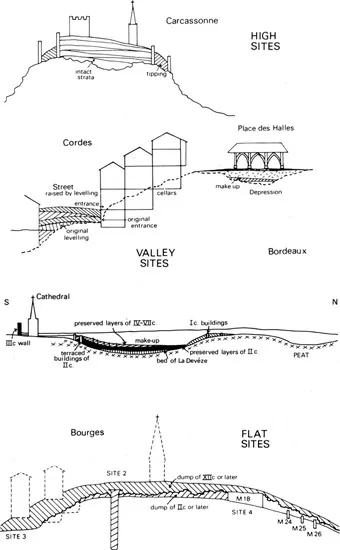

It is worth trying to understand how sites are transformed, so as to understand more surely what we find, and the study can be approached in a number of ways. As a result of being enticed by research or forced by rescue work into many strange places, archaeologists can now call on a large body of empirical knowledge (FIG 1.7). We know that sites perched on top of rocky places suffer greatly from weather and subsequent visitors, both conquerors and climbers; the deposits leave little imprint on the rock and much of the useful material has been chucked down the slope. River

FIGURE 1.5 Factors that affect the formation of archaeological deposits.

FIGURE 1.6 What happens to history: the decay and dispersal of human settlements

FIGURE 1.7 Trapping strata: some French examples (drawn by Liz Hooper).

valleys, by contrast, build up deposits, although they partly flush them out again. Rivers running through towns have often been subsequently canalised (to prevent the flooding), so their earlier deposits remain in situ, sealed in damp and often anaerobic conditions on old river banks. This has produced the set of northern European early town sites with famously rich organic preservation – Dublin on the River Liffey, York on the Ouse, Bergen on a Norwegian fjord, Bordeaux on the Garonne – the ‘organic crescent’.

In general, European successive urban occupants have not been kind to each other, undertaking periodic demolition and levelling on a m...