![]()

1 International business before the Industrial Revolution

Introduction

This chapter addresses the nature and structure of “international business” before the Industrial Revolution. As we will see later in greater detail, the First Industrial Revolution, which, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, radically changed the physiognomy of both the world economy and society, was also at the basis of a radical change in the very forms in which business was carried out internationally. A deep discontinuity with the past was created by the diffusion of new means of production and of the factory as a way of organising capital and labour in an increasing number of industries. Together with this, the presence of institutional devices able to foster the globalisation of markets was of paramount relevance. This has often induced scholars of international business to focus their attention on the historical period which followed this epochal watershed, when the embryonic precursors of the modern multinationals appeared. Right or wrong, this approach has had the consequence that very few studies which focus on the history and the economics of international business take the variety of activities present in the so-called pre-industrial age into account.

However, from another point of view, scholars interested in the history of the international economy in the centuries preceding the First and Second Industrial Revolutions are familiar with the diverse and variegated forms of international activity. Clearly, before industrialisation, international business activities took a very different shape from in the decades and centuries which followed the First Industrial Revolution and the appearance of the factory as the principal way of assembling the factors of production, as this chapter will show. However, this does not mean that international trade played a negligible role, relative to the size of the global economy, both at “national” and at global level. This perception has a lot to do with one of the paradoxes of modern thinking, which is to consider the present as being characterised by a degree of complexity which is, in all respects, much higher than in the past – and, consequently, considers contemporary human beings as more intelligent and more alert to new ideas than their predecessors. The degree of sophistication of international business activities in the pre-industrial period, which will be addressed in this chapter, militates, however, in the opposite direction. It bears witness to the fact that, before the Industrial Revolution, the activity of trading and doing business in general beyond “local” borders was not only normal and intensive, but was also characterised both by a range of solutions for complex and uncertain situations, and by a variety of organisational devices which were able to cope with “environmental complexity”, both of which were, at the very least, just as elaborate as those which we possess today, and which we analyse in advanced courses on international corporate strategy.

The aim of this chapter is thus twofold. The first is to assess the very general framework of the international economy before the First Industrial Revolution, before what historians label as the “great divergence”, to wit, the rise of the West over the rest of the world, and the consequent disruption in the overall economic and political structure of the Ancient World. Clearly, it is not necessary to stress the fact that the data and, in general, the quantitative evidence which can be put forward in this respect, are both scarce and neither reliable nor comparable with those available today. This chapter will thus be largely based upon the qualitative evidence derived from the existing research, and quantitative data will be used only for the sake of exemplification and descriptive purposes.

The second purpose of the present chapter is to describe, at a more “micro” level, the dominant forms of entrepreneurial activity which could be found in the pre-industrial economy, and also to analyse their structural characteristics in the light of some of the dominant theoretical frameworks in use in the field of international business.

1. The adventures of Pietro Querini

At the beginning of October 1432 – just some decades before the great geographic discoveries which opened up the phase of European expansion abroad – Pietro (or Piero) Querini – a Venetian nobleman, member of the Maggior Consiglio (the main governmental body of the Serenissima, or the Venetian Republic) and “capitano da mar”, as a sea captain was called in Venice – finally returned to his home town. He had been away – actually, he had been considered missing, lost at sea, or dead – since the summer of the year before, when his galley, called the Querina, left Finisterre in Spain destined for Flanders. The Querina – which had been loaded in Crete (or Candia, as it was then called), where this Venetian nobleman and merchant held some of his family possessions – was carrying a variety of merchandise which Pietro wished to sell abroad, which included a huge quantity of wine (a kind of fortified Malvasia), and spices, wax, cotton, alum and many other items which had a huge market in the northern regions of Europe. What happened to Pietro is narrated in his diary. The Querina left Crete in the spring of 1431, sailing close to the coast of the north of Africa, – and carefully avoiding Genoese vessels, given the war that had, in the meantime, begun between the two sea Republics. It first called at the port of Cádiz and then at Lisbon, before heading north at the end of the summer. Then something happened. The vessel was set off course due to a very severe storm, and started drifting, borne by the current of the Gulf Stream, which took it first to the coast of Ireland, and then to the North Sea, where it was shipwrecked around mid-December of that year. Abandoning the ship, Pietro and the remaining crew took to the two life-boats, which continued to drift in the storm. On 4 January 1432, a few survivors, all that remained of the Querina’s crew, landed on a rock near Røst, a small island in the Lofoten archipelago in Norway, well within the Arctic Circle and thousands of miles away from the original destination of the voyage. They managed to survive on this tiny island for another month, when the locals finally succeeded in rescuing them. After some months, Pietro and his fellow survivors had recovered sufficiently to start their journey home, which brought them first to Bergen and then to London, where Pietro was hosted by the powerful Venetian community. He eventually reached Venice by land, after crossing the Channel. The legend built around Pietro’s adventurous journey credits him with being the first person to import the dried white codfish known as stockfish in Norway, and as baccalà in the Venetian dialect, into the Venetian region, where it remains, to this day, a vital ingredient of some typical local dishes which continue to be based upon this totally imported ingredient.

Even if the diffusion of bacalhau (Portuguese) or baccalà in Southern Europe is attested to have occurred in the fifteenth century, the trade of stockfish between the Norwegian coast and Britain actually goes back to the ninth century; dried fish was a suitable merchandise for long-distance trade, particularly in those European countries where it was also a fundamental ingredient in the “religious” diet for lean days, typically Friday, or during the period of Lent, when meat was prohibited. It is therefore quite difficult to believe this part of the story in its entirety; there are, however, a number of elements which allow us to understand the characteristics of international business before the First Industrial Revolution in greater detail.1

One out of thousands, in Europe, Scandinavia, the Middle East, India, South East Asia and China, Pietro was regularly producing and trading wine and other commodities from his family’s estates in Crete with the rest of the Mediterranean. However, the most profitable areas for running these commercial activities were in Flanders, already a fairly rich region that had no vineyards but had to be supplied with wine, which was a basic ingredient of daily life as well as of religious practices. Pietro was thus travelling regularly from the shores of Asia and Africa to the colder regions of North Europe, and close to what could be rightly seen as the “frontier of civilisation”, connecting physically different markets, different supplies, and different, yet complementary, needs.

Pietro’s adventurous travelling is, however, also relevant for another important reason. The following section of this chapter will, in fact, depict a very general and impressionistic story of international business activities before the Industrial Revolution. The focus will be on the geographic extension of long-distance trade, its progressive articulation into a unique global system, and its overall complexity, the strategies and the forms of behaviour of merchants and entrepreneurs, and the main devices which made such a delicate mechanism function in such a surprisingly smooth way. However, such complexity could be interpreted as something involving the consumption propensity (and the purchasing power) of a handful of the happy few belonging to an élite. Economic and social historians have, however, demonstrated that the demand and consumption of exotic merchandise, or simply of goods produced in distant lands, was by no means confined to a limited number of consumers. The hundreds of tonnes of pepper, nutmeg, cloves and other spices consumed yearly by Europeans, then replaced by other mass-consumption products from coffee to tea, from cocoa to tobacco to sugar, all demonstrate how long-distance trade was able to revolutionise the day-to-day lives of people, ordinary people. The average Chinese citizen needed silver for his payments, his taxes, or as a savings fund (value storage), just like his emperor, while, in Acapulco, the descendants of Spanish expatriates were dressing their Indian mestizos (persons of mixed race, especially the offspring of a Spaniard and an American Indian), or Spanish wives in silks which came from China, across the Pacific, via Manila, or eating out of and drinking from Ming porcelain. But ambiguity and contradictions are, at the same time, part and parcel of the very nature of the pre-industrial world, in which one part is trapped in small local universes submerged in the immense ocean of the countryside, while another part is able to frame complicated networks of exchanges over long distances, making unknown and exotic items available to those who demanded them, desired them, and had the wherewithal to pay for them.

2. Long-distance trade before the industrial revolution: relevance

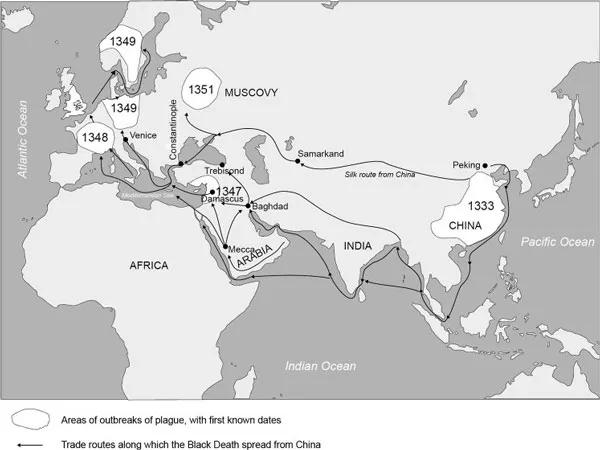

One of the first important elements which impresses the reader of Querini’s adventures is the actual extent and coverage of international trade and business activities in the pre-industrial period. The general argument is quite delicate here. As economic historians have clearly demonstrated, before the Industrial Revolution, self-sufficiency based upon the primary sector, agriculture, was the norm. The low per capita income of individuals, and the gross national product of countries and regions, were overwhelmingly based upon the rural production and the autarkic practices dominant in the countryside, which accounted for 90 per cent of all production. The rest was divided into manufacturing, services, and, of course, trading – as part of services. Intuitively, manufacturing occupied a relevant proportion of the non-peasant activities, and was mainly concentrated in the very rare – when compared to today – urban concentrations, with a sort of appendix in the rural-based putting-out system, a medieval sub-contracting system which temporarily included large sections of peasant society within the manufacturing sphere. Services were also mainly concentrated in urban settings, where self-production and consumption was less pervasive, and trading, too, had, in proportion, greater relevance in the towns than in the countryside. Trading was, in its turn, to be divided between short- and long-distance trade, two concepts which are largely relative – and intuitive. Today, this distinction is easier, since long-distance trade and international trade tend to overlap; but, in an age in which national states simply did not exist, the same distinction was far from being intuitive. Long-distance trade was better identified with the trading of commodities at a distance which was so great that all the information embodied in the commodity itself – its price at origin above all – vanished, provided, of course, that the same commodity was unavailable in the area of destination. The most intuitive example can be found in the history of spices. But spices – consumed in great quantities in the Europe of the Middle Ages – are just a symbol. Along the “silk route” and other routes travelled an endless variety of exotic items for which there were few or no substitutes at all (not to mention precious metals, such as gold and, above all, silver, which were going in the opposite direction). There was always something which was not immediately available, or which was tremendously scarce, or almost non-existent, but, by chance or fortune, was nonetheless deemed to be absolutely necessary, from wine to spices, from wood to silk, from dried fish to ivory, and even slaves. Historians have demonstrated – and continue to demonstrate – that long-distance trade activities have been less irrelevant, and less trivial, than was once estimated and than the sense of the superiority of present times allows us to imagine. And if, before the end of the sixteenth century, a solid, articulated and non-episodic system of Eurasian long-distance (in this case, intercontinental) trade was already in place, which had originated at least as far back as the thirteenth century, commerce steadily expanded like a sort of plague or contagion – with the irony that the trade routes and ships which regularly served to connect continents also served to diffuse plagues and diseases from continent to continent (see Map 1.1).

It is, of course, impossible to offer even an approximate account of the quantitative relevance of intra-European trade (the one in which Pietro Querini was just one of the countless actors), or of the intra-Asian trade and Eurasian trade, in the period preceding the Industrial Revolution, given the absence of trade statistics of any kind. However, given their relevance as a consumption item, some rough estimates are available for spices. Some calculations estimate the quantity of pepper imported to Europe every year at the beginning of the fifteenth century to be around 1,000 tonnes per year, accompanied by another 400–500 tonnes of other spices. If one considers the usually (in the absence of artificial barriers) linear relationship between per capita GDP and the consumption of both domestic and foreign goods, the fact that the absolute majority of the world’s riches was probably concentrated in Asia (and basically in India and China) at the beginning of the sixteenth century, (according to some calculations, the distribution of world GDP in the year 1500 was as follows: Europe 18 per cent, India 24 per cent, China 25 per cent, Africa 8 per cent) confirms the impression that an overwhelming part of the world’s foreign trade in all kinds of merchandise was concentrated in Asia. Furthermore, after the Black Death (the devastating plague which affected Europe in the middle of the fourteenth century (1346–1353)), the increase in the per capita income of the survivors was translated into higher living standards, and hence into an increase in consumption levels. According to some estimates, pepper consumption in fifteenth-century Europe had risen to 1,200 tonnes per year, while that of other exotic spices more than doubled, reaching 1,300 tonnes per year.

Map 1.1 The spread of the Black Death in Europe and Asia, fourteenth century

3. Long-distance trade before the industrial revolution: geographies

The integration of trade on a global scale went on during the early modern period (1500–1800), from the beginning of the sixteenth century up to the eve of the First Industrial Revolution, giving origin to a multi-layered system of long-distance trade divided into regional/national, continental and intercontinental clusters of exchange. Here, too, it is again impossible to calculate, even approximately, the total volume of trade, which, on the eve of the First Industrial Revolution, was no longer confined to Europe and Asia. After the (heroic) phase of the great geographic discoveries and of the opening of the sea routes across the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean, the domain of world trade had, in fact, extended to the rest of the globe. If we define the presence of multiple, stable, long-distance (for instance, those linking the Scandinavian countries to Southern Europe, or those established between the Italian ports of Genoa and Venice and the Black Sea or Azov region), even intercontinental trade relationships as “clusters” of exchange, then, we can affirm that at least three main “clusters” existed during the seventeenth century.

The first cluster (and the oldest, most articulated and complex) was the already mentioned Eurasian trade relationship, which was established between the Middle Ages and the early modern period, and resulted, in its turn, from the progressive integration of two already existing continental exchange systems, the European one (in its turn, a very complex array of trade sub-systems, including the Baltic, the North Sea, the Mediterranean, the continental European and the Black Sea markets) and the Asian one (largely clustered in the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea). During the Early Middle Ages (the twelfth to fifteenth centuries), these were initially integrated by a complex system of land routes crowded by caravans, largely monopolised and controlled by Muslim merchants, which flourished and prospered until the first half of the fourteenth century, thanks to the so-called Pax Mongolica (the establishment of stable political control by the Mongols of Genghis and Kublai Khan on a vast mass of lands stretching basically from the Black Sea – that is, the door to the European trade system – to Beijing). After a phase of harsh and ferocious conquests, from the beginning of the fourteen century, the Mongols began to establish safe trade routes across the territories which they controlled to such an extent that European merchants could travel safely across Asia, with or without the intermediation of local middlemen. The Pax disintegrated by the middle of the fourteenth century, and with it the temporary safety of the trade routes across Asia. This served to stimulate the invention of alternative routes, mostly by sea. These offered quicker, cheaper and, to some extent, safer transport for Europeans to reach India and its riches. They included the discovery by Vasco da Gama of the passage to the East Indies around the Cape of Good Hope (1488), which basically allowed Europeans to skip the intermediation of Muslim middlemen.

Vasco da Gama’s journey (1498) was preceded by a series of progressive discoveries along the Atlantic coast of Africa by Portuguese seamen, and ended in the establishment of a stable presence of Portuguese traders on the west coast of India, one of the world’s main commercial hubs, whose ports were already crowded with ships and merchants from Asia Minor, Persia, and from the East African coast, importing all kinds of merchandise, from Arab horses to ivory, from carpets to gold, from ebony to pearls, slaves, and dyestuffs in exchange for cotton cloth, which also constituted the main item in Indian trade towards South East Asia and China, which, in its turn, sent spices, tea and porcelain to India. Thanks to the Portuguese initiatives, Europe, coming from outside and in a latecomer position, became increasingly integrated in the...