![]()

Chapter 1

Then and Now: Planning for

Countryside Conservation

Kevin Bishop and Adrian Phillips

INTRODUCTION

Not since the Corn Law debates of the 19th century has the countryside been such a focus of political and public attention. Fundamental attitudes and assumptions that have underpinned policy in this field for more than half a century have been challenged. In recent years, a watershed has arrived: we can be sure that the future for the countryside will not be a continuation of past trends.

New tools are therefore needed to help us plan and manage the countryside at a time of unprecedented change. This is what this book is about, and in particular about the various approaches being developed to promote environmental concerns. Its main aim, therefore, is to review experience within the UK and Ireland in shaping what the Performance and Innovation Unit of the Cabinet Office has called a ‘a new national framework for protecting land of environmental value in the countryside’ (1999, p78).

The book’s more detailed aims are to:

- examine the impact of new international and European frameworks for planning and managing the countryside and its natural values;

- review the range of new tools for the identification, protection and management of land with environmental value in the countryside;

- assess the value of these new approaches through a range of case studies; and

- draw conclusions on a new approach to countryside planning.

To set the scene, this introductory chapter outlines what we mean by the terms ‘countryside conservation’ and ‘planning’, looks back at how the countryside has been planned and managed over the last 50 years, compares this with the situation now and then identifies the key themes addressed in this book.

Figure 1.1 The countryside planner’s bookshelf

DEFINING COUNTRYSIDE CONSERVATION AND PLANNING

In reality, there is no single system of ‘countryside planning’ in the UK but rather a number of separate systems and initiatives which represent an ad hoc policy response to different issues that have arisen over time. Despite the introduction of a ‘comprehensive’ system of town and country planning in 1947, planners (in a statutory sense) have played a limited role in rural land use – often being mere bystanders to the changes in landscape and loss of ecological resources that have occurred. Whilst relatively minor built development has been subject to the full rigour of planning control, major agents of landscape change, such as afforestation schemes and agricultural improvements, have been allowed to proceed outside the planning system. In reality, economic forces driving land management have shaped the countryside far more than has town and country planning.

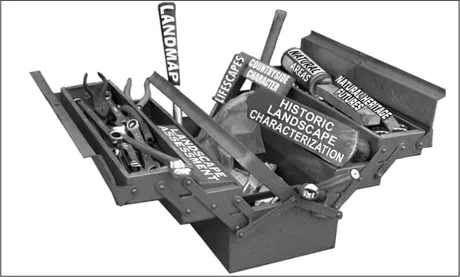

That is why our definition of countryside conservation and planning is not focused only on the statutory system of town and country planning – and the term ‘planner’ means more here than those professionals entitled to use the initials ‘MRTPI’ (Member of the Royal Town Planning Institute). Rather, we are concerned with how society plans and manages the natural and cultural heritage of the countryside in its widest sense. Thus defined, there has been a profusion of countryside plans and strategies aimed at conserving the countryside. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, the countryside planner’s bookshelf is now sagging under the weight of such documents. Moreover, a veritable toolkit of countryside planning processes has been devised to help identify, conserve and manage the natural and cultural heritage to help the planner in his or her work (see Figure 1.2).

The focus of this book is on these new frameworks and processes for countryside conservation and planning. In particular, these include:

Figure 1.2 The countryside planner’s toolkit

- methodologies to describe landscape character and natural qualities;

- historic landscape assessments;

- a national to local system of biodiversity action plans; and

- ways of involving local communities in the protection and enhancement of their own environments.

But despite these innovations, the current framework for rural policy still bears the imprint, in part, of the thinking of the 1940s. Therefore, before discussing the key themes addressed in the book in further detail, we briefly recall the origins of countryside planning and management, and how attitudes and policy have changed over the past 50 years.

THEN: A LASTING LEGACY

The prevailing view of the 1940s was clearly captured in the Scott Committee (1942) Report on Land Utilisation in Rural Areas. This held that a healthy farming industry was a sine qua non for national food policy, landscape protection and the revival of the rural economy (Cherry and Rogers, 1996). For half a century, this assumption dominated countryside planning and management. The approach that it gave rise to was characterized by the following themes, each of which is explored below:

- agricultural fundamentalism;

- containment planning;

- site specific conservation;

- functional divergence;

- domestic drivers;

- community consultation.

Agricultural Fundamentalism

In the early years after World War II, there was a clear view of what the countryside was for and what should be done to realize this vision. There was a general determination amongst politicians and policy-makers to develop further the ‘Dig for Victory’ approach to agriculture which had served Britain so well during wartime. Agriculture was seen as the primary function of rural areas and the role of farmers was to ensure food security. The role of government was to support agriculture and provide a policy framework that encouraged food production and provided a favourable environment for farmers to achieve this. Successive governments intervened in the agriculture sector in order to foster and promote domestic food production through price support, production subsidies, scientific research and special treatment for farmers within the land use planning and taxation systems. Though it took a different form after the UK joined the Common Market (now the European Union – EU), production-focused support continued, and was indeed reinforced, under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). This philosophy of what the late Gerald Wibberley called ‘agricultural fundamentalism’ only began to be seriously challenged in the 1980s, perhaps most dramatically with the arrival of milk quotas in 1984. But, despite more than ten years of continual reform to the CAP and national agricultural policy, some of the framework developed immediately after World War II remains intact (Performance and Innovation Unit, 1999; Policy Commission on the Future of Farming and Food, 2002).

Containment Planning

During the inter-war years, Britain took tentative steps towards establishing a town and country planning system, but in reality progress was slow and piecemeal. The major impetus for a national land use planning system came from a trilogy of wartime reports – Barlow (1940), Scott (1942) and Uthwatt (1942). All three reports took the view that a land use planning system should have as one of its primary duties the protection of agricultural land. The seminal influence of the Scott Committee has already been noted. It considered that planning should be about protecting farmland, and farming should have a prior claim to land use unless competing uses could prove otherwise. Such thinking was embodied in the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, which was largely designed to protect the countryside and agricultural land from urban encroachment. The planning system not only sought to contain urban development in order to safeguard agricultural land, it also imposed minimal controls on agricultural and forestry enterprises. The use of land and buildings for agriculture and forestry was (and remains) excluded from the definition of development contained in the 1947 and all subsequent planning acts; hence there is no need to obtain planning permission for agriculture or forestry operations. Also, most building or engineering operations carried out for agriculture or forestry purposes are classified as permitted development under the General Development Order (GDO) Schedule 2. Though some limited erosion of this freedom has taken place over the years, successive governments have resisted pressure from amenity and conservation interests to extend planning controls over a variety of farming and forestry activities. Indeed, strong protection of agricultural land has been the bedrock of national planning policy in the UK for over 50 years (Green Balance, 2000). In so far as the planning system has protected the rural heritage, it has been primarily achieved incidentally, through the protection of the best, most versatile agricultural land from urban development. Since the formal planning system has played such a limited role in protecting the landscape, nature and the historic heritage within the farmed and forested countryside, a range of alternative non-statutory and often innovative approaches have evolved.

Site Specific Conservation

Conservation was an important part of the post-war vision of building a ‘Better Britain’. The National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 marked the culmination of decades of argument and lobbying about the need for conservation of the countryside. Under the Act, conservation efforts were to be focused on the designation and notification of protected areas – special places identified as such because of their scientific or amenity value. For example, the newly established Nature Conservancy was charged with notifying owners and appropriate authorities of the value of ‘any area of land of special interest by reason of its flora, fauna, geological or physiographical features’ and from this the SSSI (Sites of Special Scientific Interest) ‘system’ was established. Similarly, the National Parks Commission was charged with designating National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs).

The distinction between protected and unprotected places has been fundamental to policy-making and much of the thinking about conservation in the UK over the last 50 years (Bishop et al, 1995; Adams, 2003). For many years, most people probably thought that conservation was something that took place only within protected areas.

Functional Divergence

The network of nature conservation bodies, environmental groups and countryside lobbies that developed in Britain during the first part of the 20th century was united in its concern about unregulated urban encroachment and the need for protected areas. However, these groups held different views on the purpose and function of such areas. For example, the arguments of bodies such as the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves and the Council for the Protection of Rural England (now Campaign to Protect Rural England) was reflected in the Huxley and Hobhouse Committees’ reports of 1947 on nature conservation and National Parks respectively (Hobhouse Committee, 1947; Huxley Committee, 1947). Whilst the two committees struggled for a short while to develop a unified approach, it was not long before the Huxley Committee opted to follow its own separate route. So, when Hobhouse argued aesthetics, Huxley argued science; where Hobhouse had access and public benefit in mind, Huxley had study and learning; where Hobhouse saw local authorities, working through the town and country planning system, as the chief deliverers of countryside protection and enjoyment, Huxley wanted hands-on ownership and the management of nature reserves by scientists (Phillips, 1995). The National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 incorporated these differences into legislation. By the end of 1949, the ‘great divide’ that would last for 40 years or so was in place, with National Parks and countryside work separated institutionally from that on the conservation of nature – and both quite separate from historic heritage protection. Henceforth, landscape, nature and historic heritage were to be pursued as separate policy areas (Gay and Phillips, 2000).

Domestic Drivers

Whilst those lobbying for the establishment of National Parks drew some inspiration from the experience of countries such as the US, in general the values, beliefs and approaches upon which post-war policy was based were largely domestic. There was very little influence from beyond these shores and certainly no significant international drivers to ‘push’ or ‘pull’ domestic policy until the 1980s (the first nature conservation treaty to affect the UK significantly, the Berne Convention, was adopted in 1979, which was also the year in which the Birds Directive took effect).

On the other hand the context used in post-war legislation, and subsequently, was not particularly sensitive to national differences within Great Britain. Thus the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 provided for a common system of nature conservation for Great Britain and a common system of landscape protection for England and Wales. Whilst Northern Ireland developed its own legislative frameworks, these mirrored the approach across the Irish Sea.

Community Consultation

Concepts of community engagement, enablement and participation were conspicuously absent from the thinking behind the post-war policy framework that shaped the UK’s approach to countryside conservation and planning. The model developed was one of top-down, paternalistic delivery with community involvement often restricted to a limited form of consultation under the formal planning system.

NOW: A NEW ERA?

A comparison of the legacy of the 1940s with the current context suggests that a critical point has been arrived at in terms of how we plan and manage the countryside. The consensus that characterized the approach of successive UK governments to the countryside has broken down.

First, and perhaps foremost, the predominance of agriculture has been challenged and notions of ‘agricultural fundamentalism’ potentially consigned to history – though as some anguished comments from farmers’ interests during the recent epidemic of Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) show, it retains a near-mythical following in some quarters. The evidence of damage to landscape, wildlife and historic heritage brought about by modern agricultural practices challenged the thinking of the 1940s; it suggested that the price paid by society for farming’s privileged position was too high. However, history will probably confirm that domestic food scares (such as BSE – Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) and the FMD epidemic of 2001 were the key national events in bringing about insistent calls for changes in agricultural policy. Meanwhile, at the European level the cost of the CAP, and especially of the planned EU expansion, are driving the search for CAP reform; while globally the move for change comes from pressures to liberalize trade in agricultural products. The discussion is now about how to ensure that farmers are rewarded for positive management of the countryside in an environmentally responsible way rather than being subsidized to produce food (Policy Commission on the Future of Food and Farming, 2002). The minority view expressed by Professor Dennison in an appendix to the Scott Committee report (1942) has achieved respectability at last. Furthermore, the debate is not just about what we should be conserving in the countryside but also about what to restore and enhance. Thus there is now a need for planning processes that can identify the character of different areas and guide how that character co...