![]()

INTRODUCING RURAL GEOGRAPHY

![]()

Introduction

Clear your mind and think of the word ‘rural’. What image do you see? Maybe you see the rolling green downland of southern England, or the wide open spaces of the American prairie? Perhaps it’s the golden woodlands of the New England fall, or the forests of Scandinavia? The Rocky Mountains or the sun-baked outback of Australia? Are there any people in your rural picture? If so, what are they doing? Are they working? Or maybe they are tourists? What age are they? What colour are they? Are they men or women? Rich or poor? Do you see any buildings in your rural scene? Perhaps a quaint thatched cottage, or a white-washed farmstead? Maybe a ranch, or a simple log cabin? Or do you see a run-down dilapidated home, barely fit for human habitation; or an estate of modern, identikit, housing? Is there any evidence of economic activity? Farming, probably, but then do you see a farmyard of free-range animals, as the children’s storybooks would have us believe, or do you see battery hen sheds, or endless fields of industrially produced corn? Maybe you see quarrying or mining or forestry. But what about factories, or hi-tech laboratories or office complexes? Are there any shops, or banks, or schools – or have they been converted into holiday homes? Are there any roads or traffic in your image? Is there any crime, or any sign of police on patrol? Do you see any problems of ill-health, or alcoholism, or drug abuse? Who owns the land that you are picturing? Who has access to it?

Do you still have a clear picture of what ‘rural’ means to you, or are you beginning to think that defining the rural is more complicated than you thought? There is, alas, no simple, standard, definition. Whatever picture of the ‘rural’ you have conjured up, it will probably be different from that imagined by the person sitting nearest to you as you read this book. This is not to say that we all have an entirely individual understanding of rurality. Our perceptions will be shaped by a wide range of influences that we will share with other people: where we live, where we holiday, which films we watch, which books we read. Local and national, cultural traditions are also important, as is what we learn at school, what we read in the newspapers and the political propaganda that we receive from pressure groups. In some countries, ‘rural’ is not a widely used concept at all but visitors to those countries will recognize spaces that look to them to be ‘rural’. Thus, if our understanding of what ‘rural’ means is not individually specific, it is at least culturally specific. Someone living in the crowded countryside of south-east England will probably have a different idea about rurality from someone living in deepest North Dakota. A farming family in rural New Zealand will have a different idea from a city-dwelling tourist from Amsterdam. And so on.…

Yet, if ‘rural’ is such a vague and ambiguous term, in what sense can we talk about ‘rural studies’, or ‘rural geography’ or ‘rural sociology’? This chapter introduces the different ways in which academics have attempted to produce a definition of rural, setting out the pros and cons of each approach, before eventually describing how the concept of rurality will be treated in this book.

Why Bother with Rural?

So, if ‘rural’ is such a difficult concept to define, why bother with it at all? For a start, distinctions between urban and rural, city and country, have a long historical pedigree and great cultural significance. Raymond Williams, one of the leading chroniclers of English language and literature, has observed that,

‘Country’ and ‘city’ are very powerful words, and this is not surprising when we remember how much they seem to stand for in the experience of human communities … On the actual settlements, which in the real history have been astonishingly varied, powerful feelings have gathered and have been generalised. On the country has gathered the idea of a natural way of life: of peace, innocence and simple virtue. On the city has gathered the idea of an achieved centre: of learning, communication, light. Powerful hostile associations have also developed: on the city as a place of noise, worldliness and ambition; on the country as a place of backwardness, ignorance, limitation. A contrast between country and city, as fundamental ways of life, reaches back into classical times. (Williams, 1973, p. 1)

So deep is this cultural tradition that differentiating between town and countryside is one of the instinctive ways in which we place order on the world around us. In academic usage, however, the term is more recent. Sociologist Marc Mormont, for example, has suggested that the use of ‘rural’ as an academic concept evolved during the 1920s and 1930s – a time when the countryside was undergoing major social and economic transformations – in an attempt to define the essential features of ‘rural’ society in the face of rapid urbanization and industrialization (Mormont, 1990). Very often, the definitions of rural society produced reflected a particular moral geography, with the ‘rural’ associated with values such as harmony, stability and moderation. These more judgemental ideas about the urban–rural dichotomy have been removed over time from academic thought, but the distinction remains a useful one for researchers for at least two reasons.

First, many governments officially distinguish between urban and rural areas and govern them through different institutions with different policies. For England, for example, the government published two separate policy papers in November 2000, one for ‘urban policy’ and one for ‘rural policy’, and much of the latter will be administered by the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and implemented through the government’s Countryside Agency.

Secondly, many people living in rural areas identify themselves as ‘rural people’ following a ‘rural way of life’. So strong is this sense of identity that when they are faced with problems such as unemployment, the decline of staple industry (such as agriculture) or the loss of local services, they do not build links of solidarity with people experiencing the same problems in urban areas, but rather assert their rural solidarity as a basis for resistance to a perceived ‘urban threat’. An example of this can again be seen in the UK, where over 400,000 people joined a march in London in September 2002 organized by the Countryside Alliance to protest at the perceived neglect of rural areas and rural interests by the central government (there is more on this in Chapter 14).

These two factors mean that although researchers may be able to identify the same social and economic processes at work in rural areas as in urban areas, they also know that the processes are operating in a different political environment and that the reactions of people affected may be different. The analysis of these differences, however, brings us back to the problem of what we mean by ‘rural’. Halfacree (1993) identified four broad approaches that had been taken to defining the rural by rural researchers. These are (i) descriptive definitions; (ii) socio-cultural definitions; (iii) the rural as locality; and (iv) the rural as social representation. Each of these approaches will now be introduced and critiqued in turn.

Descriptive Definitions

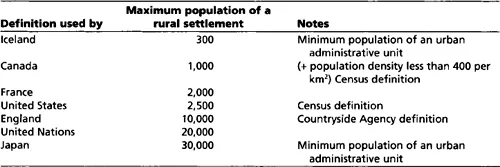

Descriptive definitions of rurality are based on the assumption that a clear geographical distinction can be made between rural areas and urban areas on the basis of their sociospatial characteristics, as measured through various statistical indicators. The simplest way of doing this is by population and this is the approach adopted in most official definitions of rural areas. After all, it appears to be fairly logical – we all know that towns and cities have larger populations than villages and dispersed rural communities. But, at precisely what population does a rural area become urban? As Table 1.1 shows, there is considerable variation in the maximum population size of a rural settlement permissible under the official definitions of rural and urban areas used in different countries.

There are other problems too. First, the population recorded depends on the boundaries of the area concerned. For example, if the population of the town in which I live, Aberystwyth in West Wales, is measured on its official community boundaries, then it comes in at just under 10,000 – sufficient to qualify as rural on some definitions. Yet the community boundary cuts right across the university campus. If the total population for the actual built-up urban area is counted, the real tally is nearer 20,000. Similarly, there are many rural counties in the United States that have larger populations than many incorporated urban areas, simply because they cover a much more extensive territory.

Secondly, simple population figures reveal nothing about the function of a settlement, or about the settlement’s relation to its surrounding local area. A town of 1,000 people in Nebraska may be a definite urban centre for a dispersed rural population, but a village of 1,000 people in Massachusetts may be perceived to be rural in its regional context. Thirdly, distinctions based solely on population are arbitrary and artificial. Why should a settlement with 999 residents be classified as rural, and one with 1,000 residents be classified as urban? What difference does that one extra person make?

Table 1.1 Official population-based definitions of rural settlements

Some official definitions of rurality have addressed these problems by developing more sophisticated models that also include reference to population density, land use and proximity to urban centres. In many countries a mix of different definitions is employed by different government agencies. For example, the website of the Rural Policy Research Institute (www.rupri.org) discusses nine different definitions used by parts of the United States government; whilst in the UK it has been recently estimated that there are over 30 different definitions of rural areas in use by different government agencies (ODPM, 2002). Many of these are actually ‘negative’ definitions in that they set out the characteristics of urban areas and designate anywhere that does not qualify as ‘rural’. Three examples of this approach can be seen in the definitions used for the US and UK censuses and by the US Office of Budget and Management:

- The US census uses population to define urban areas as comprising all territory, population and housing units in places of 2,500 or more persons incorporated as cities, villages, boroughs (except in Alaska and New York), and towns (except in the six New England states, New York and Wisconsin). Everywhere else is classified as ‘rural’.

- The UK census uses land use to define urban areas as any area with more than twenty continuous hectares of ‘urban land uses’ – including permanent structures, transport corridors (roads, railways and canals), transport features (car parks, airports, service stations, etc.), quarries and mineral works, and any open area completely enclosed by built-up sites. Everywhere else is classified as ‘rural’.

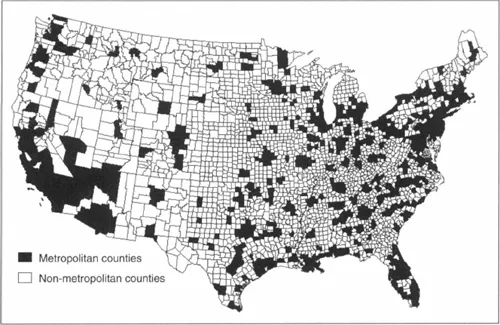

- The US Office of Budget and Management defines metropolitan areas as at least one central county with a population of more than 50,000, plus any neighbouring county which has ‘close economic and social relationships with the central county’ – defined in terms of commuting patterns, population density and population growth. Anywhere outside a metropolitan area is classified as a ‘non-metropolitan county’ (Figure 1.1). Non-metropolitan counties are the most commonly used definition of a rural area in research and policy analysis in the United States.

All three of the above definitions, however, can be critiqued on the same grounds. First, they are dichotomous, in that they set up rural areas in opposition to urban areas and recognize no in-between. Secondly, they are based on a very narrow set of indicators that reveal little about the social and economic processes that shape urban and rural localities. Thirdly, because rural areas are a residual category they are treated as homogeneous with no acknowledgement of the diversity of rural areas.

Figure 1.1 The US Office of Budget and Management’s classification of metropolitan and non-metropolitan countries In the United States

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service

Indices of rurality

In an attempt to recognize some of the differences between degrees of rurality, and to overcome the problems that resulted from defining a rural area using just one or two indicators, Cloke (1977) and Cloke and Edwards (1986) constructed an ‘index of rurality’ for local government districts in England and Wales using a range of statistics from the 1971 and 1981 censuses. Significantly, the indicators used related not just to population (including population density, change, in-migration and outmigration and the age profile), but also household amenities (percentage of households with hot water, fixed baths and inside WCs), occupational structure (percentage of workforce employed in agriculture), commuting patterns and the distance to urban centres. These indicators were fed into a formula that placed districts into one of five categories – extreme rural, intermediate rural, intermediate non-rural, extreme non-rural and urban (Figure 1.2).

Although the indices of rurality did mark an improvement on simple dichotomous definitions, it still provokes a number of critical questions. First, why choose the indicators that were used? What, for example, does the percentage of households with a fixed bath tell us about rurality? Secondly, how was the weighting between different indicators determined? Is agricultural employment more or less important than population density in determining rurality? Thirdly, how are the boundaries between the five different categories decided? At what point on the artificial scale produced by the formula does an ‘inter...