![]()

Chapter 1

What is dyslexia?

What is dyslexia? This may seem like a question that should be easy to answer, given that we have been talking about dyslexia since it was first written about by Pringle Morgan in 1896 (Squires and McKeown, 2003, 2006). We should be able to give a clear description by now and start our book with a good understanding of the phenomenon that we are talking about. However, this is not the case. The term is open to debate and means many things to many people. Understanding the debate will help to consider how we assess dyslexia; who we identify as being dyslexic; the kinds of things that we do to remediate dyslexia; and the kinds of adjustments that we can make so that the curriculum, place of study and access to work are easier for people with dyslexia to participate in more fully.

Morgan started the debate by describing a young boy, aged 14, called Percy F (Morgan, 1896). Percy was developmentally very similar to his peers, he was bright and intelligent, good at games and able to solve mathematical problems such as multiplying 749 by 867. His teacher considered him ‘the smartest lad in the school if the instruction was entirely oral’. However, Percy had great difficulty with learning to read and spell, despite having private tutors since the age of seven years. So much so, that Morgan wrote in the British Medical Journal that he thought that the cause of the problem must be congenital. This way of describing dyslexia echoes around current debates.

• Reading and spelling skills are not developing as well as other skills. There is some recognition now that reading and spelling are different processes and dyslexia could be a weakness in reading alone, spelling alone, or both reading and spelling. There is debate about how different the other skills have to be – some people argue that dyslexia is a difficulty with reading and writing irrespective of other skills. Other people argue that a differential diagnosis is needed to distinguish other reasons for poor reading and writing from dyslexia – that is dyslexia is a special case of poor reading or spelling skills. A few people argue that dyslexia as a concept is not very helpful, there is just a difficulty in reading and spelling that can be overcome with good-quality teaching (e.g. Elliott, 2005; Elliott and Gibbs, 2008).

• If it is congenital, then there must be detectable and observable structural differences in the way the brain functions that impact on reading and spelling but not general ability. Many areas of brain function have now been explored and implicated as possible causes. Another implication from this is that even when the reading and writing difficulties have been overcome, there will still be some difficulties that persist in the way that information is processed that will impact on adult life. That is to say, dyslexia is for life. Linked to this notion is the idea that other parts of the brain take over and people with dyslexia develop skills in other areas to compensate for their weaknesses – leading to the term ‘compensated dyslexic’.

• Implicit in Morgan’s description is that the apparent difficulties are not the result of poor teaching or a lack of opportunity to learn. This has been strengthened in some definitions of dyslexia (e.g. BPS, 1999; Bradley et al., 2005; D. Fuchs et al., 2003). In part this also sets up a debate about the use of medical labels in educational contexts.

• Morgan did not go on to talk about the emotional impact of dyslexia for some learners and the extent to which the educational context and socio-political agendas contribute to some children feeling inadequate as learners. These factors also lead to more children being identified as having difficulties by teachers than might be the case (Squires, 2012; Squires et al., 2012; Squires et al., 2013).

• Morgan did not consider how some of the barriers to learning might be removed and access to learning or work improved through the use of reasonable adjustments; that is, the disabling nature of dyslexia can be increased or reduced through the way in which the social world of learning and work are organised. This is consistent with the social model of disability and the capabilities framework (Burchardt, 2010). The removal of barrier to learning features in an approach used in English schools referred to as dyslexia-friendly (Mackay, 2006). This notion is central to assessments that are carried out to make examinations, study and access to work possible through ‘reasonable adjustments’, but can be taken further with careful planning that anticipates that learners will be diverse and have different strengths and weaknesses.

Dyslexia or not? Issues from teaching

Reading and writing are given high priorities in education; this has been the case since schools were inspected on their ability to teach the three Rs: Reading, wRiting and aRithmetic (or reading, recording and reckoning). In more recent years, the driving force for this has been the recognition that good literacy skills underpin economic competiveness (OECD, 2013). This has motivated many governments to attempt to strengthen the curriculum and control the way that literacy is taught and international comparisons are made that rank that country’s performance (Mullis et al., 2012). In England this led to the introduction of the National Literacy Strategy (DfEE, 1998) with a tightly defined and prescriptive approach to teaching. Each term in a child’s primary school education was mapped out with expected targets to be reached and a mechanism for judging how effectively schools met these targets.

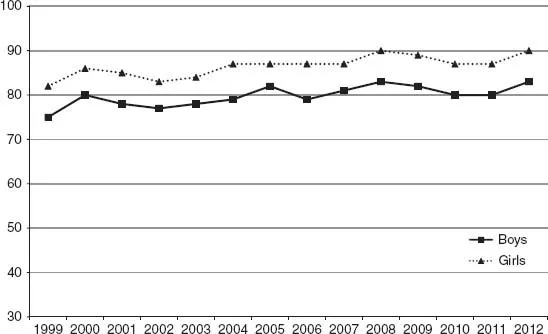

Figure 1.1 | Percentage of children reaching expected standards in reading at the end of primary education. |

On the positive side, such an approach dealt with a critique that had been levelled at teachers who did not know how to teach literacy. The National Literacy Strategy supported teachers with materials, approaches and ongoing training designed to overcome poor-quality teaching. There was a heavy emphasis on teaching phonics and phonological awareness. On the down side, the National Literacy Strategy expected all children to learn at the same pace, with learning broken down, by teaching tasks, into a daily literacy hour. The success of the National Literacy Strategy can be judged by looking at the attainment levels of children at the end of the primary phase of education. Data published annually by the government shows that the strategy made a slight difference to the percentage of children who were not achieving at expected levels in reading (see Figure 1.1). In a 12-year period to 2011, 5 per cent more children were achieving the expected levels in reading. This still meant that 20 per cent of boys and 13 per cent of girls were failing to reach this standard. Significant changes in the way that reading and writing are assessed were introduced in 2012 (DfE, 2013) and this may account for the increase in the final year.

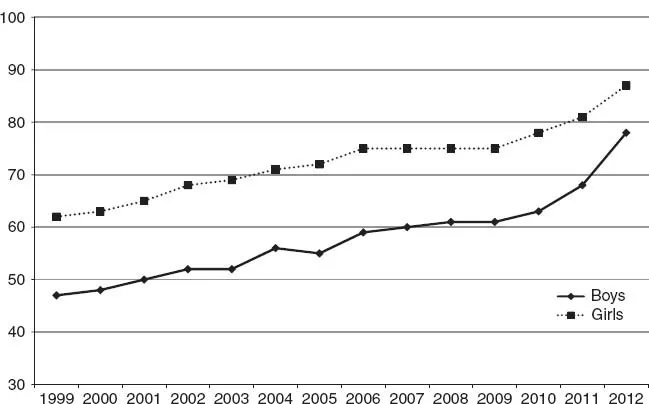

Figure 1.2 | Percentage of children reaching expected standards in writing at the end of primary education. |

The picture regarding writing looks more favourable, with around 20 per cent more children achieving the expected level (see Figure 1.2). However, in 2011, 19 per cent of girls and 32 per cent of boys failed to reach the standard set out by government.

In both reading and writing, boys appear to be underperforming compared to girls and many reasons for this have been suggested. These include that girls develop language skills earlier than boys, giving them an advantage when it comes to reading; the interest levels of materials used suit girls more than boys; the way that teaching takes place suit the more passive learning style of girls compared to boys. For a while, it was thought that there was a general feminisation of the primary school, with a lack of male role models (Parkin, 2007); however, this view is not supported by other research evidence (Driessen, 2007; Martin and Rezai-Rashti, 2009).

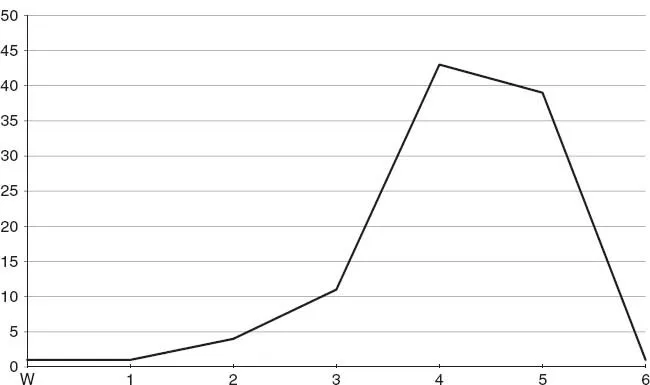

Of course, we would expect reading and writing skills to be normally distributed in the population, with some children doing better than others. There should be an equal spread about the mean, with the majority of pupils in the middle. This is not the case, the distribution is positively skewed. There is a long tail of underachievement (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 | Distribution of reading teacher assessments for pupils at the end of the primary school phase in 2012. |

The concern about the underachieving tail has been around for a while and has led to several targeted approaches to remediate poor literacy-skill acquisition. This is based on the idea that further small group teaching may make up for missed learning opportunities that have arisen for a number of reasons, such as:

• The curriculum pace being too quick for learning to be mastered and generalised, leaving pupils at the acquisition phase with incomplete learning. The small group work allows pace to be matched more closely to pupil learning and provides more opportunities to master concepts and skills. This approach sometimes fails because the learning that is taking place in the small group setting is not generalised through matched learning experiences in the main classroom setting. There needs to be good linkage between the small group work and the rest of the classroom activities.

• Pupil absence and missed learning opportunities. The materials devised for the targeted interventions allow pupils the chance to go over the missed learning.

• Behavioural or attentional difficulties that mean that, although the pupil was in the classroom, they were not accessing the lesson. Smaller groups provide more opportunities for adults to manage the behaviour or pupils’ attention, and focus them in on the learning.

There is some emerging evidence that when teachers pay more attention to the needs of children with SEN more generally these children will make more progress as teaching is matched more closely to learning needs. In the Achievement for All national evaluation, children with SEN were able to make more progress than peers in English when teachers were more focused in their approach (Humphrey and Squires, 2011, 2012).

This general shift in how teaching of literacy takes place has resulted in an approach which starts with good teaching for all and then has targeted teaching for small groups of pupils. This still leaves a few pupils for whom more intensive work is needed. The approach is being used in several countries, with slightly different language to describe the same principles. In the UK, teachers talk about ‘waves of interventions’ in which Wave 1 is referred to as ‘quality first’ teaching; Wave 2 involves small group programmes and has materials referred to as early literacy support, additional literacy support and further literacy support; Wave 3 involves specific interventions that are tailor-made for individual pupils and written into an individual education plan (IEP), requiring additional adult support. The terminology in Ireland that covers the same levels is friendlier: ‘support for all’; ‘support for some’; and ‘school support plus’ (NCSE, 2011a, 2011b; NEPS, 2010). In the US, the same ideas are ...