Child Psychology and Psychiatry

Frameworks for Clinical Training and Practice

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Child Psychology and Psychiatry

Frameworks for Clinical Training and Practice

About this book

An authoritative, up-to-date guide for psychologists, psychiatrists, pediatricians and other professionals working with vulnerable and at-risk children

Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Third Edition is an indispensable resource for psychologists and psychiatrists in training, as well as experienced clinicians who want to stay abreast of important recent developments in the field. Comprehensive in coverage and much broader in scope than competing titles, its clear, concise entries and abundance of illustrations and visual aids make it easy for busy professionals and interns to quickly absorb and retain key information.

Written by expert clinicians and researchers in a wide range of disciplines within or relevant to the fields of normal and abnormal childhood development, Child Psychology and Psychiatry includes contributions from clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, child psychiatrists, pediatricians, speech pathologists, and developmental psychology and psychopathology researchers. It has been fully updated for the DSM-5 and reflects the theoretical, structural, and practical developments which have taken place in the world of child psychology and psychiatry over recent years.

- Combines a strong academic and research emphasis with the extensive clinical expertise of contributing authors

- Covers normal development, fostering child competence, childhood resilience and wellbeing, and family and genetic influences

- Discusses neurobiological, genetic, familial and cultural influences upon child development, especially those fostering childhood resilience and emotional wellbeing

- Explores the acquisition of social and emotional developmental competencies with reviews of child psychopathology, clinical diagnoses, assessment and intervention

- Features new chapters on the impact of social media on clinical practice, early intervention for psychosis in adolescence, and the development of the theory and practice of mentalization

Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Third Edition is an indispensable learning tool for all of those training in clinical psychology, educational psychology, social work, psychiatry, and psychiatric and pediatric nursing. It is also a valuable working resource for all those who work professionally with at-risk children and adolescents.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Section 1

Developing Competencies

1a: Contextual Influences Upon Social and Emotional Development

1

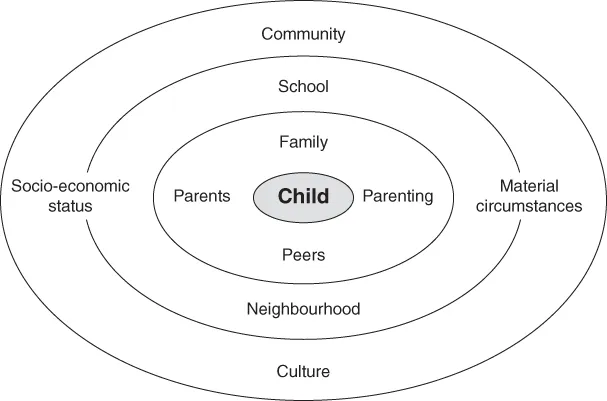

Family and Systemic Influences

Family Relationships and Parenting

- Indulgent (responsive but not demanding) – parents are non‐traditional and lenient, allow considerable self‐regulation, and avoid confrontation.

- Authoritarian (demanding but not responsive) – parents are obedience‐ and status‐oriented, and expect orders to be obeyed without explanation.

- Authoritative (both demanding and responsive) – parents are assertive, but not intrusive or restrictive. Disciplinary methods are supportive rather than punitive. Children are expected to be assertive as well as socially responsible, self‐regulated as well as cooperative.

- Uninvolved (both unresponsive and undemanding) – most parenting of this type falls within the normal range, but in extreme cases it might encompass both rejecting–neglecting and neglectful parenting.

- Discordant/dysfunctional relationships between parents, or in the family system as a whole

- Hostile or rejecting parent‐child relationships, or those markedly lacking in warmth

- Harsh or inconsistent discipline

- Ineffective monitoring and supervision

Parent and Family Characteristics

Sibling Relationships

Changing Family Patterns

Parental Separation and Divorce

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Section 1 Developing Competencies 1a: Contextual Influences Upon Social and Emotional Development

- Section 1 Developing Competencies 1b: General Patterns of Development

- Section 2 Promoting Well‐being

- Section 3 The Impact of Trauma, Loss and Maltreatment 3a: Trauma and Loss

- Section 3 The Impact of Trauma, Loss and Maltreatment 3b: Maltreatment

- Section 4 Atypical Development in Children and Adolescents

- Section 5 Assessment and Approaches to Intervention

- Index

- End User License Agreement