eBook - ePub

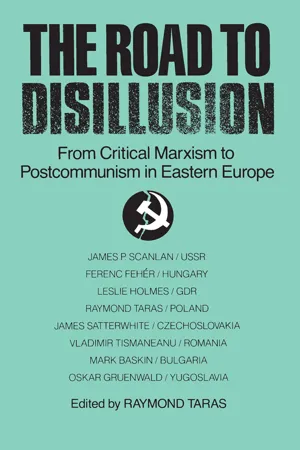

The Road to Disillusion: From Critical Marxism to Post-communism in Eastern Europe

From Critical Marxism to Post-communism in Eastern Europe

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Road to Disillusion: From Critical Marxism to Post-communism in Eastern Europe

From Critical Marxism to Post-communism in Eastern Europe

About this book

The history of reform movements in postwar Eastern Europe is ultimately ironic, inasmuch as the reformers' successes and defeats alike served to discredit and demoralize the regimes they sought to redeem. The essays in this volume examine the historic and present-day role of the internal critics who, whatever their intentions, used Marxism as critique to demolish Marxism as ideocracy, but did not succeed in replacing it. Included here are essays by James P. Scanlan on the USSR, Ferenc Feher on Hungary, Leslie Holmes on the German Democratic Republic, Raymond Taras on Poland, James Satterwhite on Czechoslovakia, Vladimir Tismaneanu on Romania, Mark Baskin on Bulgaria, and Oskar Gruenwald on Yugoslavia. In concert, the contributors provide a comprehensive intellectual history and a veritable Who's Who of revisionist Marxism in Eastern Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Road to Disillusion: From Critical Marxism to Post-communism in Eastern Europe by Raymond C. Taras in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Política1

The “Meltdown” of Marxism in the Soviet Bloc

An Introduction

For historians, fin-de-siècle Europe may in time become closely associated with fin-de-communisme in the former Soviet bloc. On the threshold of the 1990s, in the countries that used to comprise geopolitical Eastern Europe as well as in individual republics that made up the USSR, Marxist ideocracies abruptly collapsed under the weight of nationalist sentiment, free-market impulses, and liberal democratic values. State Marxism became discredited and even reformist and critical schools of Marxism no longer served as centers of philosophical controversy. To the extent that ideological discourse was perceptible in these states, it was characterized by a bandwagoning process of siding with victorious counter-Marxist ideals. A witness to fin-de-sièclisme in the region would do well to recall an aphorism of, appropriately enough, Winston Churchill: “Defeat is an orphan, but victory has a thousand fathers.” Today in the old Soviet bloc, Marxism has indeed been orphaned.

Why undertake a study of East European Marxism now, in view of the historic political changes that occurred in the region in 1989? Put another way, what can we learn from the fate of Marxism in the shattered Soviet bloc? The objectives of this book are to describe how Marxism as critique helped undermine Marxism as ideology, and at the same time to show how oppositional Marxists dissected “real”—that is, “actually existing”—socialism to expose the failings of the system. This study is about the process of dismantling the ideocracies that were established when Marxism was adopted as a totalistic state ideology, and it is about the intellectual Odysseys of one-time Marxists who were increasingly repulsed by the official ideology and sought alternative belief systems. In this respect the book chronicles the road certain Russian and East European thinkers traversed from Marxist faith to disillusionment.

It is now clear to Soviet and East European specialists that the socialist states they study were built with a doctrinal house of cards. Because Marxism—and the economic relations and political and legal superstructures it engendered—crumbled so quickly in societies as different and distant from one another as Central Europe and Central Asia, the Balkans and the Baltic states, East Germany and Azerbaijan, there had to have been much less life left in the ideology and its institutional appendages than was commonly believed. It becomes all the more important, therefore, to examine the philosophical and ideological thrusts that initially helped weaken Marxism once the Stalinist era ended. This volume undertakes a cross-national analysis of these thrusts in eight states of the former Soviet bloc, including the USSR itself.1

The central thesis that informs this study is, then, the existence of linkage, however tenuous and indirect, between recent political change and past Marxist dissent in the Soviet alliance system. In seeking to capture the contradictions inherent in Marxist ideocracies, we might want to argue that what undermined Marxism in the Soviet bloc was precisely the coexistence of the “two Marxisms” about which Alvin Gouldner wrote—the “scientific” Marxism adopted by socialist states and the “critical” Marxism appropriated by those opposed to monolithic Muscovite ideology.2 Such an argument oversimplifies the range of Marxist thought in existence while also distorting the relationship between the two, which oftentimes could be complimentary as well as antagonistic. We use the term critical Marxism in a more specific way than Gouldner: it includes theorists who utilized the Marxian paradigm as the basis for a critique of the real socialism of the Soviet bloc and who remained political outsiders rather than members of the ruling elite. The pioneer of dissent against the Stalinist model of socialism in the postwar period was Josip Broz Tito. As a power holder himself, however, he defined Yugoslavia’s state Marxism, which in turn engendered an idiosyncratic variant of critical Marxism in that country. In 1953, five years after he had triggered the schism with Stalinism, the Yugoslav leader’s understanding of the socialist project was itself challenged by the Marxist dissident Milovan Djilas. Elsewhere in the Soviet bloc, Marxist revisionism remained until 1956 largely an “ivory tower” form of dissent, limited to debates and conflicts over arcane and obscure philosophical issues. Nonetheless, even such differing and nuanced interpretations of the Marxian world view, based on exegesis and couched in Aesopean language, represented the first cracks in the monolith of Marxism that had been constructed by Lenin and consolidated by Stalin.

After Khrushchev’s 1956 de-Stalinization speech, revisionism—the Marxist-grounded critique of official state Marxism—began to spread to intellectual circles not subordinated to the party. Before successive eras of dissident activism, samizdat, underground organizations, then broader social movements, revisionism represented the most serious challenge to the ideological state apparatus of communist regimes. Its crowning success was the selection of Alexandr Dubček to head a liberal Marxist administration in Czechoslovakia in January 1968. But Dubček’s normative framework remained alien to the country’s ideological apparatus: the latter remained impervious to critical Marxist penetration, and to that extent the Czechoslovak leader remained an outsider to official Marxism. Revisionism’s grand failure came with the overthrow of Dubček’s shaky coalition of liberal Marxists following the Warsaw Pact invasion of August 1968.

With hindsight we know that revisionist Marxism was neither as insurrectionary and “counterrevolutionary” as then-communist rulers made out, nor was it particularly successful in bringing about political change. To employ Robert Sharlet’s terminology, its principal goal was to engage in “self-limiting dissent” that “demonstrated varying degrees of deference to the unwritten ‘rules of the game.’”3 To give the early revisionist Marxists their due, they began the process of corroding the state ideology with liberal and democratic ideas, as chapters in this volume describe. Many in their number were “creeping democratizers” whose chief objective was to expand democracy within the communist parties. Others, like the eminent Soviet physicist Andrei Sakharov in his early writings, were willing to entrust democratization of the political system to the Communist Party.4 The manner in which their programs were veiled was Marxist, and they fully merited the epithet “loyal opposition.” Over time, it is possible to see how they eroded official Marxism until it ceased to provide guidelines to action for the communist leaders themselves.5

There is a logical and persuasive explanation for the plethora of Marxist analysis conducted in the failing socialist systems of the 1960s and for the threat it posed to political rulers. Michael Shafir put it this way: “It is indeed hardly conceivable that criticism formulated in terms other than the Marxian jargon would have been considered seriously or would have provoked any response other than brutal and immediate suppression.” But in addition to this defensive tactic adopted by Marxist revisionists, Shafir also underscored its longer-term, offensive thrust: “Criticism employing a Marxian ‘frame of reference’ is a necessary stage… in the effort to institute ‘civil society.’”6 For in a strange way, the amount and level of creativity of Marxist critiques under socialism served as a barometer of the strength and vitality of opposition to incumbent rulers. No less an authority on political dissent under socialism than Adam Michnik stressed the centrality of revisionism in carrying the struggle to the communist regimes.7

Critical Marxists: Posttotalitarians or Maggots?

Let us accept, then, that critical Marxists were crucial to the early struggle against the Leninist party-state. They were pioneers in the effort to create independent space for philosophical discourse, and in their critiques they were among the first to reject totalitarian culture. In this capacity they helped (applying Jeffrey Goldfarb’s thesis) to “deconstruct the distinctive totalitarian amalgamation of force and a purported absolute truth” and to “bring into being very significant changes in the politics and language of officialdom and officially accepted critics.” They therefore represented an embryonic form of the post-totalitarian mind.8 The emergence of critical Marxists into intellectual life opened up an autonomous public sphere not only because they successively proselytized about “humanist Marxism,” thereby expanding the breadth of discourse and the number of its adherents; they also represented models of activism rather than of apathy, of political engagement in contrast to the sense of political inefficacy prevalent within society at that time. By the 1970s, they went beyond self-limiting dissent to put forward “contrasy stems” serving as alternative social, cultural, and even economic models.9 Finally, as Stuart Hughes wrote, even if for no other reason, “those who thought or think otherwise deserve respectful attention.”10

From this account the reader may conclude that early critical Marxists were nothing short of romantic revolutionaries singlehandedly taking on the power of the socialist state in the quest for liberal and democratic values. So let us for a moment portray critical Marxists as unromantic revisionists. In Miklós Haraszti’s study of the cultural intelligentsia under socialism, a more sanguine analysis of the role of the well-meaning dissident is presented. Progress in liberalizing the state’s hold over the individual is reduced to the discovery that what the writer “can publish today would not have been published yesterday…. It is indeed very good to be alive and write things my father could not have written.” Were not the critical Marxists who are the subject of this book just such unambitious and smug liberals, readily bought off by the smallest of concessions? Worse, were revisionists not the social reformers of Haraszti’s metaphor?

This “struggle” is like an argument between an old-fashioned prison warden and a humane social reformer with a well-developed aesthetic sense. The latter wishes to replace the rusty iron chains with designer shackles. The warden fails to understand. The reformer becomes so vexed that he declares that jailers should not meddle in the business of handcuff production, as clearly everyone prefers stainless steel: it is better and more pleasing to look at.11

Clearly there were critical Marxists involved in the reproduction of ideological purity who preferred the aesthetic look of Marxism cast in stainless steel rather than corroding iron. From accounts given in the essays that follow, the reader will observe different trajectories in their political careers. Sometimes such argumentation caused them to be co-opted into the ideological state apparatus, as in the case of the Soviet Union during the heyday of perestroika. At other times and in other places, the preference for “stainless-steel Marxism” led to loss of party position and even to execution, as in the case of Romania after the war. Most often, such preference eventually evoked a transition to “melancholy Marxism” in its adherents and then a move away from Marxism altogether, as witnessed in the generation of disillusioned Poles who experienced the communist regime’s backlash following the March 1968 protests.

A question related to the fate of apologetic Marxists is the extent to which they may have bought time for the socialist regimes of the Soviet bloc. The answer must be not at all. On the contrary, even putting different window dressing on the doctrine was likely to produce cognitive dissonance among the initiated; and for the rest of society, the very act of revising part of a petrified ideology probably served to justify existing skepticism and, in this way, proved dysfunctional to the state-socialist colossus. The fact that apologists themselves converted in great numbers to other ideological pathways underscored the fragility of their original doctrine.

What status did oppositional Marxists enjoy when the systemic transition to postcommunism began in Eastern Europe? Even in the generally anticommunist climate of the region in the early 1990s, there was grudging recognition of the part played by reformist communists in attacking the socialist system. Let us take the case of Poland. In an article titled “Tomb of the Unknown Reformer,” an establishment journalist of the ancien régime, Daniel Passent, wrote, “The tragedy of revisionists-liberals-reformers is that they desired improvements, they possessed good intentions, they perceived the crisis of the state and of the formation that engendered it.” But what happened subsequently was that “reformers became disillusioned and were discarded by both their own circles and those of the opposition.”12 At the other end of the political spectrum, the noted editor of an underground journal, Marcin Król, in characterizing the transition to postcommunism, observed how “the orphans in this process are reform-communists. I feel sorry for them. They started the process of change and now they are disappearing.”13 Sympathy for the plight of Marxist reformers thus came from radically different political positions. Similar recognition of the contribution yet transience of Marxist reformers could be found in some of the other ex-bloc states.

As a possible clinching argument in defense of the approach taken by critical Marxists, we can refer to Timothy Garton Ash’s observation that “it is easy now to forget that until almost the day before yesterday, almost everyone in East Germany and Czechoslovakia was living a double life: systematically saying one thing in public and another in private.” Marxist-based discourse was f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- 1. The “Meltdown” of Marxism in the Soviet Bloc: An Introduction

- 2. From Samizdat to Perestroika: The Soviet Marxist Critique of Soviet Society

- 3. The Language of Resistance: “Critical Marxism” versus “Marxism-Leninism” in Hungary

- 4. The Significance of Marxist Dissent to the Emergence of Postcommunism in the GDR

- 5. Marxist Critiques of Political Crises in Poland

- 6. Marxist Critique and Czechoslovak Reform

- 7. From Arrogance to Irrelevance: Avatars of Marxism in Romania

- 8. Bulgaria: From Critique to Civil Society?

- 9. Praxis and Democratization in Yugoslavia: From Critical Marxism to Democratic Socialism?

- Name Index

- Subject Index