eBook - ePub

Leadership

Succeeding in the Private, Public, and Not-for-profit Sectors

- 445 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Leadership

Succeeding in the Private, Public, and Not-for-profit Sectors

About this book

The contributors to this wide-ranging volume seek to define exactly what leadership is or should be, and how to effectively develop it. Guided by an unusual framework that looks at leadership across different sectors and functions, they examine what they view as the major leadership challenges in highly visible for-profit, not-for-profit, and government organizations throughout the world. Their insights will prove equally useful as a general survey of leadership problems for executive policy makers, and for undergraduate and graduate students in the specific fields examined in the text.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Leadership by Ronald R. Sims,Scott A. Quatro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Werbung. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

LEADERSHIP IN FOR-PROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

CHAPTER 1

FROM MONOPOLY TO COMPETITION

Challenges for Leaders in the Deregulated Investor-Owned Utility Industry

R. KEVIN MCCLEAN

The $300 billion electric energy industry and $100 billion gas industry have been undergoing changes driven by market forces and concomitant regulatory initiatives during the past two decades. Utility managers are being challenged to redefine the regulated utility’s role in the energy market, address competitive challenges where only a few years before none existed, and respond to increasing consumer demands for excellent service quality and customer service. At the same time, utilities must contain costs in an environment that is less receptive to “cost-plus” rate regulation, and motivate a workforce to meet the expectations of the various stakeholders during a period of transformational industry and organizational culture change.

The leadership challenges brought on by these changes can be viewed through prisms of a change from a production orientation to a marketing orientation and a related organization culture change:

• Marketing Orientation. What does a marketing orientation mean to regulated utilities? What are the implications for employees and managers? Does regulatory oversight apply, or should the market drive the level of customer satisfaction demanded of and met by the utility?

• Culture Change. Regulated investor-owned utilities have operated since the 1930s as quasi-governmental agencies known for job security and paternalistic management. What forces are changing this relationship and how do utility leaders cope with the change?

We will identify the issues confronting utility management and discuss how adopting a marketing orientation applies to the utility’s response to external market forces and the utility’s internal organization.

BACKGROUND: THE DEREGULATED ENERGY INDUSTRY

The energy marketplace has been undergoing significant change over the past twenty-five years. Regulated at both the state and federal levels, this industry is being transformed from a regulated industry to one where competition either has been introduced or is in the process of being introduced for the purchase of electricity and gas by commercial and residential consumers, as well as for direct contact business functions such as billing and call center operations. As will be discussed, other elements of the value chain remain—for now—under regulatory control. Why competition in what has been viewed as a natural monopoly? Following the trend of deregulation in other industries, such as telecommunications and airlines, it has become axiomatic that competition will result in benefits to the consumer. Societal benefits including reduced costs, innovation, and improved services are expected to accrue as a result of competition in the energy marketplace.1

Along with this industry restructuring, new consumer issues are being identified and addressed, principally in the area of competitive functions. Activities heretofore provided by the regulated utilities such as meter installation, meter reading, call center operations, and billing are now subject to competition (CA 1997; MA 1997; NY 1997; PA 2000; TX 2000; WI 1997).

Under the umbrella of regulation, utility leadership was primarily concerned with the safety and reliability of the systems to which they were entrusted and with achieving the allowed rate of return provided by regulators. The latter was arrived at through a regulatory rate-setting process at the state level, and this is still the case. The former, safety and reliability, is usually measured based upon agreement between regulators and utilities, oftentimes with rewards or penalties for performance (performance-based ratemaking).

There are several overriding issues that drive a desire for deregulation, including downward pressure on prices, increased customer choice, and additional services (NY PSC 1996, 4):

• Competition in the electric power industry will further the economic and environmental well-being of New York State. The basic objective of moving to a more competitive structure is to satisfy consumers’ interests at minimum resource cost … and consumers should have a reasonable opportunity to realize savings and other benefits from competition. …

• Any new electric industry structure should provide: (a) increased consumer choice of service and pricing options; (b) a suitable forum for promptly resolving consumer concerns and complaints. …

• Pro-competitive policies should further economic development in New York State.

Cost is a significant concern in the electric and gas energy business. The generally accepted concept of increasing supply in order to decrease price via competitive forces has been a driving truism for regulators and others promoting deregulation in the energy industry. A United States Department of Energy (US DOE or DOE) study projected consumer savings on a national basis (US DOE 1999).2

There is wide acceptance within the industry that competition will drive down prices to the end user over the long run (Train and Selting 2000; McDermott et al. 2000; Gordon and Olson 2000; Goulding, Rufin, and Swinand 1999; Day and Moore 1998; Jovin 1998). Such acceptance is evident in the several commission opinions cited previously, and extends beyond the cost of the commodity into other customer care functions, including billing and metering (Gordon and Olson 2000; Joskow 2000). This expectation is supported by experience in other deregulated industries. According to Winston (1998) and Crandall and Ellig (1998), the airline, trucking, railroad, and telecommunications industries all realized reduced prices following deregulation.

Innovation includes technological innovation and service innovation. The advent of bill presentation and payment processing using Internet technology is one example of innovation that can affect the gas and electric industries, along with other electronic innovations (Tschamler 2000; Borenstein and Bushnell 2000; Joskow 2000).

Service innovation can be found in offerings of bundled services, such as combining electric and gas billing with cable and telephone or other accounts (Flaim 2000; Joskow 2000; Gordon and Olson 2000). Services offered may also include management of customer electric appliances and systems, such as heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems. Another form of service innovation is the supply of electricity produced by environmentally friendly sources of power—for example, “green” energy such as solar, wind, or hydroelectric power (Joskow 2000).

Finally, improvements in customer satisfaction and service quality are to be expected in a competitive marketplace (Gordon and Olson 2000; Joskow 2000; Tschamler 2000; Jones 1998). These terms, “customer satisfaction” and “service quality,” are bedrock issues in the discipline of marketing. As with cost and innovation, the presumption is that competition will drive the players in the marketplace to provide better service than their competitors, benefiting the consumer. That service may well be tied into currently available technology (e.g., Internet-based transactions, real time pricing, or automated meter reading), improved call center operations, or simply more personalized and responsive services.

The range of issues with which the utility leadership must cope stemming from these shifts in the industry includes whether and how to compete in the production business as wellhead operators, pipeline managers, or power plant operators; whether and how to invest and maintain an adequate transmission system; how to finance adequate distribution facilities at the local level; how to address questions of organizational restructuring; and whether and how to enter competitive markets, and if so, which ones. Transcending all of these is the issue of how the utility leadership ensures that the utility is seen by the publics it serves as a valued and integral part of the energy market. To do so, it is critical that the utility understand its customers’ expectations and operate in a way that will meet or exceed those expectations. We see this as the need to apply a marketing orientation, “regulated” notwithstanding, and as the probable need to change organizational culture.

THE MARKETING CHALLENGE

For over sixty years, energy utilities existed without the “invisible hand” of competition to guide the forces of its marketplace. Rather, regulation acted as a surrogate for the economic forces that exist in an open and competitive industry. Utility leaders—and some in the industry may take a contrary view of the priorities assigned—were primarily concerned first with the reliability and safety of their production and delivery systems, then with the financial performance of their companies, and finally with the satisfaction of employees and customers. The industry was largely the domain of engineers and financial managers able to design and finance an ever more complex system of production and distribution from national gas pipelines, interconnecting electric transmission systems, and larger and more efficient electric generators, to local delivery in dense urban areas, rapidly expanding suburban neighborhoods, and far-flung and remote rural areas. And, for sixty plus years, the systems worked. Reliability of gas and electric systems is simply expected, almost taken for granted by the consumer.3

But now, with the exigencies brought on by deregulation, utility leaders are being asked to go beyond reliability and safety and meet customers’specific wants and needs, to adopt a customer focus. This is a very different emphasis from the production orientation of the regulated environment—produce and deliver enough product to economically meet demand, and use average-costs methods for determining price—and calls for utility leaders first to ask what it is that customers want, and then to plan and implement actions to satisfy those wants. At the same time, regulatory strictures continue to affect pricing for the delivery systems.

THE EVOLUTION OF MARKETING

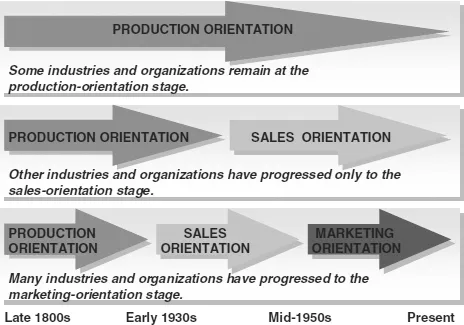

Figure 1.1 shows the evolution of production, sales, and marketing orientations over time. Energy utilities have tended to be production oriented. Gas utilities have been more sales oriented as that industry competes directly with oil for home heating in many areas of the country or as fuel for electricity production.

• Production Orientation. Utilities having a production orientation would view their only responsibility to the customer as ensuring that product (electricity or gas) is available to the customer when needed. Regulators set prices after public hearings and a regulatory process established within the state systems, and bills are rendered to customers based upon consumption.

• Sales Orientation. Utilities having excess capacity of either electricity or gas would focus efforts on enticing customers to buy more of their products without specific regard for how customers may need or use the products, making sales orientation dominant.

• Marketing Orientation. What is meant by a “marketing orientation?” Essentially, it calls for every employee in a firm to focus on satisfying the wants and needs of the customer; it claims that customers do not so much buy a product or service as seek to have their wants and needs satisfied and that firms exist to produce satisfied customers (Drucker 1954; Levitt 1960). Consistent with this is the construct that the customer, not the firm, determines value (Levitt 1960).

This thinking regarding marketing orientation has evolved from the 1950s through the 1990s and has become a dominant view in many industries (Vargo and Lusch 2004). We will further consider two views of marketing orientation in some detail, that of Slater and Narver (1992) and Frederick E. Webster, Jr. (1994, 2002), but first we ask, why a marketing orientation for utilities?

Figure 1.1 | The Evolution of Marketing |

Source: Etzel, Walker, Stanton (2004), p. 7.

Why a Marketing Orientation for Utilities?

Rate regulation is the lifeblood of a utility. It is the way the utility obtains financial resources to operate while earning returns that would entice investors to purchase utility securities. In setting electric and gas rates, utility commissions—under whatever name a state may give to that ruling body—weigh many factors and can be influenced by a myriad of interested parties, from business organizations to consumer groups to other entries to the new competitive industry, the energy service companies.

A simplistic application of a marketing orientation is the view of electric and gas energy as satisfying basic needs such as physical (warmth or cooling, light), safety (security lighting, security systems), or even esteem (using alternative fueled vehicles that run on compressed natural gas or rechargeable batteries, contributing to societal benefits). That view would miss a critical point: that all products are packaged in services and it is the service accompanying the product that will help to meet customers’ wants and needs and result in satisfied customers. The services will drive customer satisfaction. This new “dominant logic” is the thesis of Vargo and Lusch (2004) and has application in the utility industry. A customer focus and market orientation is critical to the success of the utility, if a re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Leadership in For-Profit Organizations

- Part II: Leadership in Not-For-Profit Organizations

- Part III: Leadership in Government Organizations

- Part IV: Leadership Across Multiple Organizational Contexts

- Part V: Global Leadership

- About the Authors

- Index