![]()

A Definition of Urban Culture

Urban culture has two levels of meaning for us in this text. One level of urban culture is how the city has impacted its citizens, businesses, social organizations, spatial organization, and artistic production, just to give a few examples. Culture is anything that humans make or use in their environment, everything from hammers and nails to a house that these materials construct are all culture. These are examples of what we call “material culture,” but there is another kind of culture that a city can impact that we call “nonmaterial culture.” All of the ideas, laws, beliefs, songs, poetry, religious thoughts, art norms, and folkways in a society are nonmaterial culture. A lawbook is an example of material culture in that it was constructed out of blank paper, ink was printed on the pages, and it was physically bound together to make a book. It is also an example of nonmaterial culture, because the laws and ideas in the book are not the ink on the page, but exist in the collective consciousness of the society. Finally, a lawbook could be an example of urban culture if perhaps it was a collection of municipal laws and codes for that city. Obviously, the city impacted these laws and codes, because they pertain only to that city, and they are part of the urban culture, because the city influenced their production.

The second level of urban culture is how the citizens, businesses, social organizations, spatial organization, and art affect the city. For an example, we will turn to Green Bay, Wisconsin, and the effect one particular kind of sports culture has on the city. Few football fans are as loyal or devoted to their NFL franchise as the urbanites in Green Bay are to the Green Bay Packers. The fans, called “cheeseheads” have supported this football franchise to Super Bowl wins and through losing seasons, and they have put Green Bay on the urban map of America, despite its small size of about 120,000. The citizens’ devotion to the football team, even though it is the smallest city with an NFL team and insists on playing in an outdoor stadium through the brutal winter months, have spawned businesses devoted to the team and to creating fans that have required urban road and airport modifications to accommodate home games, making the city’s stadium a holy relic of urban football culture. These citizens and the culture that they have produced have definitely had an impact on the city.

THEORIES OF THE CITY

Our first assumption in this book is that the city matters, that there is something unique about living in the city: (1) the city affects the individual and (2) groups of these individuals in turn change the city. Just as the natural environment influences what grows and survives in the wild, the city influences the patterns of growth and association of its citizens; but the difference is that citizens can change their environment and the city. How these forces work to make the city and the city’s culture unique is the focus of this text. To understand the city we should start with the various theoretical perspectives sociology has developed to analyze the city. There are four main urban theoretical perspectives that can illustrate the effects the city has on the development of culture:

1.Urban Conflict Theory—Engels and Marx, followed by John Logan, Harvey Molotch, and Manuel Castells

2.Urban Ecology Theory—Robert Park, Ernest Burgess, Amos Hawley, then improved upon by Walter Firey

3.Urban Anomie Theory—beginning with Georg Simmel, then Louis Wirth

4.Urban Culturalist Theory—Herbert Gans and Howard Becker

Urban Conflict Theory

Certainly one of the first theorists to acknowledge the importance of the city was Frederick Engels, longtime writing partner of Karl Marx. Called Conflict Theorists today, Marx and Engels focused on the disproportionate power that the different classes have in society (working, middle, and upper) and the changes to society that occur when these classes wield that power. They felt that the working class made the wealth of the upper class, but because of the upper class’s control of social and political power, the working class was denied their share of the society’s resources. Engels was attempting to find a way to visualize for his readers the plight of the working class, whose cause both Marx and Engels devoted their lives to champion.

He found his illustration in the slums of England’s cities, like Manchester and London. He described the wretched urban existence of the people who had been thrown off their land in the rural districts surrounding London and were now the cheap wage labor of the industrialists in the 1840s. Compared to the opulence of how the aristocracy and capitalist class lived in Manchester, the working class’s conditions were appalling. (Few apartments were more than closets, constructed like wood shacks with planks as sidewalks to keep pedestrians from the mud, no pavement for roadways, no running water, no waste service, no sewage, no gas or electric lights, and only small coal stove heaters for warmth that often as not were responsible for terrible fires that killed whole housing blocks.) It was clear from Engels’s descriptions that not only did the city function as a warehouse for cheap labor, it also housed a disparity of infrastructure from the policed and paved avenues, private gardens, estate grounds, and parks of the rich to the squalor of the shantytowns, rooming houses, slums, and pubs of the working class. Marx’s own work regarding the city shows the urban environment is like a theater stage set for class conflict with little special about the city, save the density of workers needed for the revolution. The work of Engels shows his improvements on Marx’s urban theater analysis, and Engels’s inflammatory writing becomes the precursor of a journalistic style of writing that will change America’s view of its cities.

Jacob Riis pioneered investigative journalism and social commentary with his descriptions and pictures of the city in the 1890 book How the Other Half Lives. In fact, his work literally created a new kind of urban culture, which is the journalistic examination of the darkest places in our cities and the lowest classes in the cities. While critical of the urban conditions, Riis wasn’t advocating a Marxian revolution. He was, however, informed by the Marxian tradition of class analysis that the lower classes were living a wretched life that wasn’t their fault. This brand of journalism was labeled “yellow journalism,” because of its association with satirical cartoons of the day, which were illustrated with yellow print colors. While not sociological theory, Riis’s work informed the mass of citizens about the disparate social conditions of the different social classes and was an extension of Engels’s work on the urban working class.

Max Weber (1921) was also influenced by the work of Marx and Engels, but being more concerned with methodological rigor he wanted a more coherent way to analyze the city than previous European Marxists. Weber’s examination of the city led to four main points of distinction for urban areas.

1.Economic relations are paramount in the city. Rural areas have the capacity to sustain themselves by growing food, while urbanites have to base their lives on commercial transactions.

2.Cities are connected to larger social institutions that act upon cities in their environment. These social institutions, like governments and international economies, are able to shape and influence cities.

3.Social networks and associates in the city combine to form an interrelated association that distinguishes urban life. Weber felt that the networks and processes in the city could help the civilization process.

4.The city is an autonomous and self-sufficient unit: legally, politically, and militarily. From this autonomous state, the urbanite develops a loyalty and allegiance to the city.

These distinctly urban elements were part of Weber’s analytical model. Class and status would be a part of Weber’s analysis as a concept he called “life chances,” which incorporated economic, social, political, and educational variables. The city would be a component of an individual’s life chances, but unlike Marx and Engels this wasn’t Weber’s first priority; Weber was attempting to develop a methodology to study the city.

Urban Ecology Theory

Another urban perspective we will examine in depth is called urban ecology, which came from the Chicago School of sociology. These theorists were the first to develop a new systematic way to analyze the city that was different than the previous work by European sociologists like Tönnies, Marx, and Weber. Beginning at the University of Chicago in the 1920s, Robert Park and Ernest Burgess were the sociologists that developed and first noticed the effect of greater numbers of people living in the city. Before this time cities were a minor phenomenon of interest in America social science, since 80 percent of the United States and an even greater percentage of the world’s population lived outside of cities; when cities were examined, their significance was only thought of as a container of social or historical occurrences. Few sociologists or anthropologists felt that the container or arena that social groups or classes existed in was important to understand, but the sociologists of the new sociology department at the University of Chicago did feel it was important. They began to notice social patterns in the city and found that the city’s residents were unique. An example of one of the uniquely urban cultural patterns that urban ecologists discovered was a common vernacular usage—blue-collar and white-collar workers.

They discovered this urban cultural phenomenon by doing old-fashion qualitative research observations … they stood on a street corner. By observing the workers go by on their way to work they noticed that those workers with blue shirts, blue collars, and name plates most often worked in manual, working class jobs and those that wore a white shirt, white collar, and a tie worked in management positions in office buildings. So, an urban culture phenomenon was chronicled by these sociologists, and it was unique to the urban environment, since most rural employment didn’t necessitate these clothing distinctions between workers and managers.

Human ecology analyzed the city in an almost biological fashion, in which the city was viewed as an organism that processes raw materials from the surrounding area to reproduce what it needs to sustain and expand itself. Like an organism, the city will grow in a predictable fashion with specific features or organs, i.e., a central business district, transportation arteries, and workers’ housing. As the city grows in a region, a hierarchy of cities develops with certain cities performing specific functions in the environment and the most dominant city performing the key function or dominant function. The key function is the ability of a city to be dominant in some industry or service in the region, usually this is because of the size or location of the city. A city that can direct and coordinate an industry or service, and is dominant in that industry or service, is performing the key function. It is like being at the top of the food chain for cities in the region.

FUNCTIONALISM AND MICROSOCIOLOGY

The competing sociological perspective to Conflict Theory in sociology is Functionalism, which fits into the framework of Urban Ecology Theory, but is not exactly the same. Influenced by the earliest fathers of sociology, August Comte and Emile Durkheim, Functionalism believes we can know and classify group behavior completely with enough quantitative study. That societies tend toward order and equilibrium, and that groups are composed of individuals who are making rational choices in their life to increase their pleasure and decrease their pain. Crime, riots, violence, poverty, and so forth are temporary fluctuations in society’s balance as people make “irrational choices” temporarily. For cities, the ordered, efficient planning of streets and services makes sense to Functionalist theorists, who feel that urban problems are just temporary symptoms of urban areas that aren’t working, but that do work most of the time. Cities function as a social unit, not because the elite classes exercise some draconian power to make them work, but because most citizens want the city to work. So, society is not held together by naked aggression and power, but by a degree of consensus from each class level.

A third perspective in sociology ignores the “Grand Theory” debate between Conflict and Functional Theory about class, power, and consensus and instead concentrates on the social psychology of small groups. Microsociology or Symbolic Interactionism, as it is sometimes called, focuses on how we construct meaning and identity in the small groups (family, friends, coworkers) we interact with every day. George H. Mead is one of the key theorists in this perspective, and his work illustrates how all the symbols (language, actions, and gifts) and identities (our work role, family role, friend role) we use every day combine to produce the reality we call “the city.” Symbolic interactionists maintain that these symbols and identities are much more meaningful to our daily lives than the amount of power or consensus that is exerted over our work lives. Cities then become arenas of complex and overlapping identities and symbols that make urbanites “different” in the way they react to and process social stimuli, because of the influence of the urban environment. The unique way that urbanites deal with these symbolic interactions is urban sociopsychology.

This white-collar worker is wearing a “uniform” that conveys a certain cultural significance in the urban landscape, enabling complete strangers to make assumptions about his work environment and job status without ever exchanging words with him.

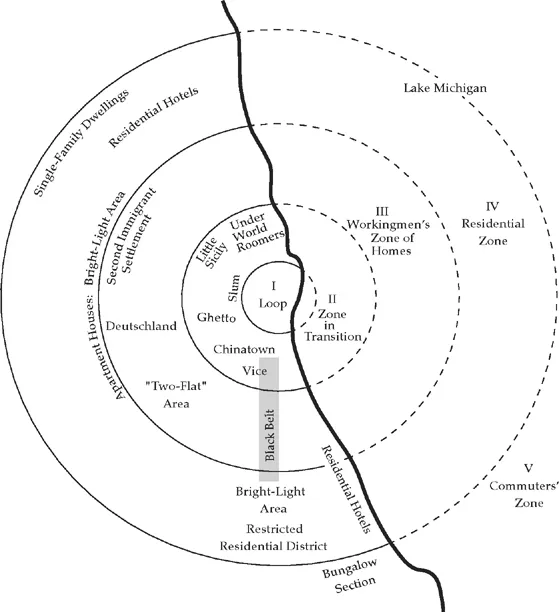

The now familiar ringed model of the city by E.W. Burgess (1925) came from this “ecological” approach (Figure 1.1).

As we examine this model, which Burgess applied to Chicago, it is important to remember that this is an ideal type1 of a city, rather than a specific city like Chicago that prescribes exactly how a city has to develop. The rings labeled in his model don’t really extend into Lake Michigan, they are to demonstrate where the Central Business District (Ring 1-Loop) or worker’s housing (Zone III) would extend if the city wasn’t located next to a lake. The rings around the Central Business District were found in other cities that Burgess examined, but specific neighborhood locations like the Black Belt or Little Italy varied from city to city and by the city’s ethnic composition.

Figure 1.1 Chicago’s Concentric Zones

Source: From “The Growth of the City,” in Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess, eds., The City. Copyright © 1967 University of Chicago Press, p. 55, chart II. Reprinted by permission of the University of Chicago Press.Source: From “The Growth of the City,” in Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess, eds., The City. Copyright © 1967 University of Chicago Press, p. 55, chart II. Reprinted by permission of the University of Chicago Press.

The Zone in Transition, an area where deviant culture and the culture of the urban marginal thrive, potently illustrates the city’s effect on urban culture. Burgess and Reckless (1925) write that cities ascribe a place for these cultures to exist; i...