Design Knowledge

In Europe we are spoiled. Our rich urban history has given rise to an equally rich and varied urban heritage right across the continent. Tourists travel from around the world to enjoy and experience our historic urban centres, and we care for them (typically) with great dedication. They have character and coherence; they ( feel comfortable and engaging; typically they are mixed, dense, and walkable; and often they are loved and valued by inhabitants and visitors alike. They are ‘places’ of character and coherence (1.1).

Figure 1.1 Central Copenhagen, a place of character and coherence

Yet beyond these centres and the often leafy, medium-density, nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century districts that typically surround them, the picture is not so rosy. Instead it mirrors the sorts of sub-urbanism found around the world. Indeed an EU-funded project conducted to explore housing design and development processes across the continent concluded:

It seems that whatever the system, whatever the governance, no matter what our rules and regulations, however we organise our professions, and no matter what our histories, placeless design seems to be the inevitable consequence of development processes outside our historic city centres. Moreover, this is despite the ubiquitous condemnation of such environments as sub-standard by almost every built environment professional you ever meet.

(Carmona 2010: 14)

Such critiques are broad indeed. They apply to the majority of our planned post-war suburbs and contemporary urban extensions; to most peripheral office, retail, and leisure parks; to our inner-urban estates; to peri-urban areas in general, including the large swathes of land along our urban arterial corridors and around our ring roads; and to new settlements (where they exist) in their entirety; to almost anywhere a coherent and unifying human-centred urban structure has been allowed to break down or where one never existed in the first place. These sorts of environments are what some have termed ‘placeless’, and they are certainly global: they are the parts of cities to which tourists never venture (at least not on purpose); are unremarkable, incoherent, and often unloved; and typically require inhabitants to adopt carbon-intensive lifestyles simply to get around. We all know such environments and likely as not will live or work in one. Increasingly they have become the urban norm rather than the exception across much of the world, and in the not too distant past even threatened to overwhelm and replace many of the historic centres we now so jealously guard.

So why do such places come about? Looking at the question through a design lens, we can logically postulate a number of possible reasons.

We Don’t ‘Design’ Places at All

Some places are clearly shaped by a network of ad hoc uncoordinated hands, where individual physical interventions—for example a building or a piece of infrastructure—may be designed, but only in relation to narrow functional requirements and not in terms of a contribution to a coherent greater whole. The whole, in this sense, is not designed and is arrived at unintentionally. Whilst this mirrors the way that many of our most cherished historic urban fabrics grew—incrementally and without a ‘grand plan’, yet giving rise to a strong sense of internal coherence—today the scale, rate, and complexity of change has hugely increased, as has the range of building technologies available to us, our infrastructure needs, and a preference amongst many development, political, professional, and individual interests for drivable as opposed to walkable urban form. All this makes unintentional coherence far less likely to occur and may give rise to the question: are the resulting built environments designed in any real sense at all?

We Don’t Know How to Design ‘Good’ Places

Today, of course, few developed societies rely on such uncoordinated incremental development to meet their development needs. Instead, places are shaped by highly trained professionals from a variety of background disciplines, most notably architects, planners, civil engineers, landscape architects, and developers, and this work is coordinated through a plan or strategy to ensure that individual interventions contribute to something larger such as a neighbourhood. Yet despite our undoubted ‘expertise’, the education of traditional disciplines has often omitted to cover the key urban design knowledge and skills required to shape places holistically and in a coordinated manner. As a consequence the skills and knowledge needed to guarantee that the place in its entirety is well designed and coherent may be (and often is) sub-standard; places are designed, but not very well. As the adage goes, ‘a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing,’ and in this field, sub-standard skills and knowledge poorly applied has the potential to do profound and long-lasting damage.

We Know How to Design ‘Good’ Places, Yet We Fail to Do So

A final cause of poor place design might be our inability to deliver good design despite having carefully constructed normative frameworks and clear visions for what places should be like. In such circumstances, it is not our design skills or knowledge that is lacking, but instead a host of other local contextual factors that have the potential to frustrate implementation and defeat even the most noble of design propositions. These might include economic barriers to change; insensitive and overbearing regulatory processes; land-ownership or land availability barriers; lack of political leadership; NIMBY pressures; or perhaps differential aspirations about what should be built between key development actors: developers, politicians, communities, and the range of built environment professionals.

Simplistically we can summarise this trinity of barriers as: no design knowledge, poor design knowledge, and ineffective design knowledge, and today, one or more of these states is likely to explain most sub-standard place design. This raises three further questions: (i) what do we mean by ‘design’ in the context of urban places; (ii) if design processes are sub-standard, what is filling the gap; and (iii) what anyway do we mean by design ‘quality’ in such circumstances?

What Do We Mean by ‘Design’?

For many, the term ‘design’ will often have narrow associations with the creative activity of drawing or otherwise conceptualising a particular object that is being ‘designed’. When used in the context of designing the built environment, for many, this will conjure associations with the creation of plans and propositions to demonstrate how particular buildings, landscapes, or urban townscapes might look—in other words, a demonstration of their aesthetic qualities. In this book, however, ‘design’ has a broader meaning in two senses.

First, design concerns all the elements of place—land uses, activities, environmental resources, and physical elements (buildings, spaces, infrastructure, and landscape)—that constitute urban environments and that transcend the professional remits of architecture, urban planning, landscape architecture, and urban engineering. In short, urban design. Second, design in this sense does not just refer to the activities of the ‘designer’, from whichever profession, but instead encompasses the sum of all the activities that together shape the built environment (intentional and unintentional)—a meta-process that has been characterised as a place-shaping continuum (Carmona 2014b).

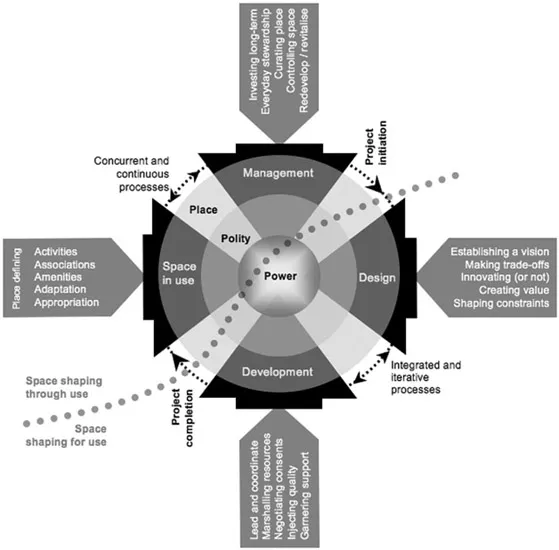

Figure 1.2 The place-shaping continuum (adapted from Carmona 2014b)

The place-shaping continuum (1.2) hypothesises that the process of shaping places cannot be grasped (and thereby steered) without understanding the full range of influences that act together to shape the process and thereby the outcomes of urban change. This implies a process: informed by historically defined norms and practices of development that vary from place to place; set within and modified by the local contemporary political economic context, or ‘polity’; and defined by a particular set of stakeholder power relationships that again will vary from place to place and even from development to development.

Within this macro-context, there is also the need to understand the creation, re-creation, and performance of the built environment across the four interrelated process dimensions represented in 1.2. Thus it is not just design, or even development processes that shape the experience of space, but instead the combined outcomes and interactions between:

- Design—the key aspirations and vision, and local contextual and stakeholder influences on a particular project or set of proposals.

- Development—the power relationships, and processes of negotiation, regulation, and delivery for a particular project or set of proposals.

- Space in use—who uses a particular place, how, why, when, and with what consequences and conflicts.

- Management—the responsibilities for stewardship, security, maintenance, and on-going funding of place.

This is not a series of discrete episodes and activities, but instead a continuous integrated process or continuum; sometimes focussed on particular projects or sets of interventions (design and development) to shape the physical environment for use; and sometimes on the everyday ‘processes of place’ (use and management), shaping the social environment through the manner in which places are actually used and looked after. We can conclude from this that the design of the built environment at large represents an on-going journey through which places are continuously shaped and re-shaped—physically, socially, and economically—through periodic planned intervention, day-to-day occupation, and the long-term guardianship of space. As a process, it is multidimensional, multi-actor, and often poorly understood, and this inherent complexity forms an important context for all the discussion that follows in this book.

What Do Sub-standard Places Have in Common?

Whilst a complete absence of self-conscious design processes—‘no design knowledge’—would be extremely rare in the developed world, arguably ‘poor design knowledge’ and ‘ineffective design knowledge’ are the norm. Take Rome, for example, perhaps the most historic of Europe’s capital cities, and boasting an enviable urban heritage with the likes of Piazza Novona, Via del Corso, Piazza del Campidoglio, Piazza della Rotonda, and Via Vento. But move beyond the ancient city and into its expanding suburbs and we find very little evidence of a carefully considered urban design process. Instead, in these areas developers and their architects focus on the buildings (typically standard building types repeated from place to place), whilst urban planning focuses on the production of two-dimensional zoning plans. No one focuses on the bit in the middle, the public realm, which remains largely un-designed. As a result, instead of being linked by a coherent and connected urban fabric that encourages walking and social and economic exchange, we see buildings constructed in unrelated plots with the spaces between dominated by parking and roads, and by very little else (1.3). Instead of a corner shop or café, these new suburbs rely on their privatised malls to serve their low-density ‘edge city’ communities.

Figure 1.3 Edge city, Roman style

In Rome, the results are all the more surprising given the historic context, but perhaps they shouldn’t be. This is simply the global norm that UN Habitat tells us is fast engulfing many developing as well as developed nations “as real estate developers promote the image of a ‘world-class lifestyle’ outside the city” (2010:10). They report, for example, that between 1970 and the year 2000, the surface area of Guadalajara in Mexico grew 1.6 times faster than the population whilst similar urban sprawl is consuming considerable amounts of land in cities as diverse as Antananarivo, Beijing, Johannesburg, Cairo, and Mexico City, to name just a few.

Regulations as a Substitute for Design

What unites all these places, as well as their counterparts in developed Europe, North America, Australasia, and the Far East? A major factor seems to be the shaping of cities through crude standards and regulations as a substitute for actually engaging in a place-centred design process. As a consequence, regulations prescribe parking norms, road widths and hierarchies, land uses, density requirements, health and safety issues, construction and space standards, and so forth. Typically, these forms of control are limited in their scope, technical in their aspiration, not generated out of a place-based vision, and are imposed on projects without regard to outcomes (Carmona 2009b: 2649). Moreover, once adopted, there is a tendency for such standards to become the norms that are then applied everywhere, even in the historic city cores (1.4).

Eran Ben-Joseph traces the evolution across North American cities of what he refers to as these ‘hidden codes’ (2005a). In doing so, he argues that too often the original purpose and value of the codes are forgotten as the bureaucracies put in place to implement them do so in a manner that has little regard for their actual rationale, and even less for the knock-on effects of their existence. Emily Talen agrees, arguing that worthy social purposes such as the pursuit of public health are all too quickly buried under the weight of successive technical amendments (2012: 28). Instead, these forms of standards are about achieving minimum requirements across the board (regardless of site context), whilst in many cases the slavish adherence to standards has led to the creation of bland and unattractive places.

Figure 1.4 Suburban-style developments located on Liverpool’s historic Pier Head, complete with standard parking requirements, road splays, and buffer planting

In the United Kingdom, such critiques go back at least as far as the 1950s and to the emergence of the townscape movement with its concerns for the sorts of ‘prairie planning’ that standards-based housing layouts were giving rise to (Cullen 1961: 133–137). Arguably this represents a classic case of regulatory (rather than market) failure, but the failure extends well beyond the suburbs and beyond the sorts of standards imposed by the public sector. The little Thames-side town of Erith on London’s eastern fringes represents a case in point.

Erith has medieval roots and grew up as a port, serving at various times as a naval dockyard, general anchorage, riverside resort, and locus for industry. The town ...