![]()

1

Three City Design Challenges

Cities in developed countries are spreading out over farms and forests faster than current city designs can keep up; climate change has introduced a dangerous uncertainty into what once appeared to be a stable natural environment; and informal settlements, which lack most of the basic support needed in a modern city, are growing quickly in many parts of the world. These are three of the most important challenges to effective city design today.

The Challenge of Rapid Urbanization

At the beginning of the twentieth century, cities housed only 15 percent of the global population. Today more than half the people in the world live in urban areas, some in traditional cities, some in the kind of decentralized development often criticized as urban sprawl, and some in unplanned informal settlements. Rapid urbanization has been accompanied by exponential population growth. The number of urban dwellers today exceeds the number of people living in the entire world as recently as 1960.1 While much of the new urbanization is taking place in Asia, Africa, South and Central America, the United States is expected to add more than a hundred million people during the first half of the twenty-first century. Most of that growth is expected to take place within ten multi-city regions in such places as Florida, Southern California, and the Pacific Northwest, while elsewhere rural areas and some older cities lose population or grow slowly. Even where population growth is slow, rapid urbanization continues in response to migration out of older areas and increased demand for housing created by the smaller sizes of individual households. Spreading urbanization is taking place even in European countries with stable or shrinking populations.

At one time, cities could be expected to remain recognizably the same for centuries. Urban change speeded up at the beginning of the nineteenth century with the interaction of railroads, factories, and fast population growth. Even so, about 1910, at the beginning of the worldwide city planning movement, it was possible to believe that traditional street and park design strategies that went back to the Renaissance could bring order and beauty to urban central areas, and what was then the new Garden City concept could evolve to manage urban change in suburbs and new factory towns. This consensus was soon challenged by the modernists, originally a small radical group, who believed that modern cities should be built on hygienic principles to maximize sunlight and open space, using what were then the new technologies of highways and steel-framed towers to sweep away the accumulation of the past. The modernists rejected the traditional relationships between buildings and streets in favor of a separate grid of traffic ways enclosing large blocks where buildings are located for optimal sun exposure. After the great economic Depression of the 1930s and the horrific disruption of World War II, most city designers switched to a simplified version of modernist design ideology, relying on automobile transportation, tall buildings, and park space as the way to rebuild and expand cities, although some traditionalists objected, and a few visionaries urged much more radical systems technologies.

City designers have had a substantial influence over urban commercial centers, communities for rich people, and mass housing for the poor, but have only been able to change urban development at the margins, as large parts of any city had been constructed over previous generations and regional growth trends include many decisions outside the control of designers.

Now the scale and speed of urbanization and decentralization have turned the management of urban growth and change into an entirely new problem. Urbanization is happening so rapidly in China that city districts can be constructed or rebuilt in a few years, and whole new cities created. By government decree, Shenzhen has grown from a fishing village in 1979 to a metropolis of more than 9,000,000 people. It is routine for planners and designers working in Planning Institutes in China to see their maps and sketches translated into reality at a scale and speed that earlier generations of frustrated visionaries would never have believed possible. The cities of the United Arab Emirates like Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Doha are also growing fast, acquiring their glittering skylines in little over a decade. Cities like Bangkok, Jakarta, and Mumbai have changed out of all recognition in the past 50 years. In the United States, the pace of new construction has often overwhelmed the official planning and regulation system, particularly where urban growth is taking place in communities with little experience in managing development at anything like the scale at which it is going forward. The US housing industry builds an average of about 1.5 million houses and apartments a year, 2 million a year at market peaks and 1.2 million a year when times are bad for building.2 Much of this construction takes place in master-planned communities of several thousand units, and all of it requires approvals by the local government. However, very little of this new housing implements a community or regional design, but instead responds to available land and the initiatives of individual builders. In Canada, a country with an economy comparable to the United States, there are stronger policies to make individual developments fit into a larger picture. In the Netherlands, the Scandinavian countries, and Singapore, large areas, if not the whole of each country, can be said to have been constructed according to an overall design. In Korea, the United Kingdom, and most western European nations, there are strong local design controls, national planning concepts, and a new interest in what is called spatial planning, another name for regional design. However, as the world speeds towards a population of nine billion people or more by mid-century, the influence of the city designer is still marginal in large parts of both the developed and developing world, even while the built environment is being reconstructed and expanded at a pace and scale that require direction.

Climate Change as a Challenge to City Design

Traditionally city designers had been able to assume that the natural environment was a stable background for their work, its forces understood and controllable through engineering. More recently, the entire trend of urban development is being revealed as unsustainable, not just because of the waste of resources created by spreading urbanization and decentralization, but because the climate of the Earth itself has become far more unpredictable. The destruction of much of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 has become an important indicator of what to expect from global climate change, although this particular tragedy need not have happened. New Orleans had relied on flood walls and levees built by the US Army Corps of Engineers. They should have protected the city from a storm of Katrina’s intensity but both the engineering and construction turned out to be defective.3 The coastal defenses for New Orleans have now been rebuilt to the standard they were supposed to have met in the first place, but the reconstruction of the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods is still far from complete.

Officials in other vulnerable coastal locations like Boston, New York, and Miami have begun to look at what would happen to them if they were hit by a comparable disaster. As a result, New York City was somewhat better prepared than New Orleans when the metropolitan New York regions were hit by Tropical Storm Sandy in the fall of 2012. But despite preparations, flood tides overwhelmed the sandbags and other protections in Lower Manhattan and poured into subway and vehicle tunnels, an electrical sub-station flooded, knocking out power for days in much of Lower Manhattan, and mechanical equipment in many buildings was destroyed by water. There was severe damage along the shore in New York City’s outer boroughs and in adjacent areas of the New Jersey and Long Island coast.

Large areas of Miami and Miami Beach are only a few feet above sea level, and are thus exposed to a direct hit by a storm surge, even one less intense than Katrina. Boston is equally at risk in the wrong set of circumstances. Would these cities be written off the way large parts of New Orleans still appear to have been? And what happens to all coastal cities as the world’s climate changes?

There is now consensus that climate change induced by human activities is a real and serious problem, and is happening faster than was predicted only a few years ago. Some of the scenarios for what could happen if the average surface temperature of the oceans rises more than 2 degrees Celsius are truly horrifying.4 Preventing the worst potential climate consequences for industry and urbanization will clearly have to become a city design priority, and this will mean designs with less dependence on automobiles, more preservation of the natural environment, and much more concern about the location and orientation of buildings for energy efficiency.

Adapting cities to the effects of climate change will be another priority. Some ocean temperature increase has already taken place, and more is already inevitable. Sea level rise is a component of climate change that is relatively easy to predict. Sea levels rise because warmer water occupies more volume, and because land-based glaciers are melting. A conservative prediction is a worldwide rise in sea levels of half a meter (a foot and a half) by mid-century and at least a meter (a little more than 3 feet) by 2100. This amplifies the threat to coastal cities already at risk from storm events. For example, according to this prediction, much of Miami Beach will be below sea level in 2100.5

Planning for future sea level rise will change the way designers think about cities. Pudong, the new skyscraper district of Shanghai, was largely freshwater wetland up until 1990. In retrospect, it was not a good place to make such a big urban investment. The low-lying islands being created by dredging off the coast of Dubai do not look like such a good investment decision either.

The Netherlands, where about a quarter of the country is already below sea level, and half of the remaining land is no more than a meter above the sea, is clearly on the front line of climate change, under threat from rising seas and also from increasing amounts of river water coursing through the country because Alpine glaciers are melting. After terrible damage from a storm in 1953, the Dutch created a system of storm-surge barriers that guard the Eastern Scheldt delta and Rotterdam harbor. Television news stories of people flooded out of their homes in New Orleans and other Gulf Coast communities have caused the Dutch to take another look at their fortifications, particularly dikes that might contain construction from hundreds of years ago. They are also looking at ways to accommodate periodic flooding from rivers by channeling the waters into park areas or farmland. The City of Rotterdam has released a plan for making the city climate-proof. These efforts are supported by a national policy to protect the whole country from the worst possible event: the 10,000-year storm. In that context, the idea of paying for whatever is necessary to protect the country from storms has been taken out of politics, giving it a similar status to the military budget in the United States. There may be discussion about the value of specific programs, or the amount of spending in a given year, but the idea of defense is not at issue. The government in Britain funded a storm-surge barrier in the Thames to protect London after a destructive surge from the same 1953 storm that caused such damage in the Netherlands. Design is now under way to raise the Thames Barrier to deal with rising sea levels, as the barrier is expected to become inadequate by 2030. Flood surge barriers have recently gone into operation in St. Petersburg, and barriers are under construction to protect Venice from flooding. Most countries, however, are a long way from a consensus about protecting coastal cities and about how to pay for it. Rebuilding in Gulfport and Biloxi, east of New Orleans, and also hard-hit by Katrina, goes forward without any investment in protective measures beyond what can be done on individual properties.

Climate change is also predicted to increase the duration and severity of drought. Although specific predictions are difficult, places that suffer from drought now, such as Australia and the American Southwest, can expect that the problem will become worse. Making cities sustainable in areas subject to drought will require major changes in city and building design. It is probable that people will look back in amazement at the days when purified drinking water was used to irrigate lawns and flush toilets.

The Challenge of Informal Settlements

In many developing countries, cities or parts of cities are growing with no design in mind at all: Robert Neuwirth estimates that a billion people, perhaps a third of all urban dwellers, and almost a seventh of the world’s population, live in squatter, or informal, settlements where there is very little control over design and development.6 The number of people moving to cities has overwhelmed the existing supply of housing that newcomers can afford, and attempts by governments to create more places to live have completely failed to keep up with what is needed. What happens instead is that people take over places that appear to be unclaimed, often on steep hillsides or flood plains along rivers which are officially considered unfit for habitation. The settlers build homes for themselves using whatever materials they can obtain. Although the whole settlement is illegal and there are no official property rights or other aspects of the rule of law, a system grows up where the strong protect their own status and weaker families can buy protection. There are no water, sewer, or power systems, but organizations develop to deliver water, and tap into power lines—illegally but effectively. Sanitation and storm drainage are usually big problems, and access is difficult, but the settlements become too entrenched for local governments to interfere, and public employees are often afraid to even enter the area.

Over time, informal settlements can evolve into workable communities, as individual families improve their housing from makeshift shacks to multi-room buildings constructed of permanent materials, but sanitation, protections from floods and landslides, and the absence of police and fire-fighting systems remain major problems.

Informal settlements mobilize the ingenuity and resources of individuals and families to create communities. The challenge is to find a way to channel this valuable energy so that informal settlements can evolve into permanent, desirable districts of the larger urban region.

The Four Approaches to City Design Today

This book starts in the present; and defines cities as urbanized regions that contain cities, suburbs, and separate towns. The history of organized human settlements goes back to villages formed when people first developed agriculture and began to give up a nomadic existence some 12,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence of larger, more complex places, defined as cities, has been dated to 8000 or 9000 years ago. The story of the economic and social forces that created cities and villages, and the ways they have been shaped and reshaped over time according to different design concepts, has been told many times; what concerns us is what this history tells us we should do now.

Today there are four different approaches to city design in use around the world which, in this book, are defined as Modernist, Traditional, Green, and Systems. Each has strong advocates, who frequently find little merit in the other three. In this book, each design approach is described in a separate chapter, which begins with a significant current example, then goes back to show how the particular way of designing began and has developed, and concludes with more current examples of each type of design, selected because they are likely to influence future development. The final chapter (Chapter 6) describes how each design approach will be needed to help meet the challenges facing city design and development today. A new synthesis can bring together the best of each.

Modernist City Design

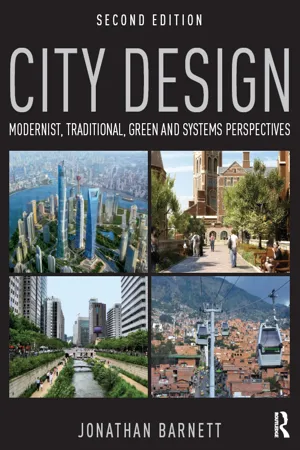

Modernist concepts, described in Chapter 2, have dominated city design since World War II. Criticisms of modernist city design have grown intense as more and more of it has been built around the world: especially its failure to accommodate historic preservation and conserve existing neighborhoods, its role in promoting social inequity by concentrating poor people in the least desirable areas, the disruption created by highways running through the center of cities—a fundamental city design concept for modernists—and the destruction of the natural environment as urbanization spreads over larger and larger regions. The tall building enabled by modern construction materials is the most significant element of modernism in city design. Modernism advocates free-standing buildings separated from their surrounding urban context. Groups of buildings are related to each other only by proximity, or by an abstract composition of separate buildings organized on a level landscape, plaza or street system. Modernist city design can produce spectacular skylines, but, at ground level, there is seldom much coherence or amenity. This rendering, of the Lujiazui financial district in Shanghai, as seen from the air (1.1), shows how a modernist city design implemented since the early 1990s has transformed ...