One of the most extraordinary features of post-war international history was the rapid disintegration of the British Empire. The largest empire the world has ever known, covering 25 per cent of the globe and about one-quarter of its people, successfully weathered economic depression and global warfare in the first half of the twentieth century. By the mid-1960s, however, those territories painted pink on the map had been reduced to a ramshackle and relatively insignificant set of islands and dependencies. Between 1945 and 1965 alone the population under British rule diminished over one hundred times from 700 to 5 million (Louis, 1999). In the early twenty-first century there were just 200,000 inhabitants of the British Empire, whose components had been re-styled ‘Overseas Territories’. The empire shattered into a set of new, independent nation-states, most of whom found a new relationship of legal equality with Britain within the Commonwealth. In 1973 Britain entered the European Economic Community (later styled European Union), signposting the end of imperial grandeur. The break-up of the empire was the most visible manifestation of contracting British global economic and military power. As one of the earliest analysts of this colonial collapse reflected in 1963, ‘we have indeed been living through one of the great transformations of human history’ (Barratt Brown, 1963: 190).

Britain’s withdrawal from empire can be divided into two main phases. The first phase encompassed the dismantling of Britain’s empire in South Asia between 1947 and 1948 – most dramatically involving the independence and fateful partition of India. The British also pulled out of Palestine in this phase. The ‘loss’ of the rest of the empire did not immediately follow, however, since Africa and Southeast Asia took on new significance for imperial economic and military strategy. The second phase of withdrawal began only in 1957 with independence for the first black African nation south of the Sahara, Ghana. It ended about 1967 as the ‘wind of change’ blew its path through east and central Africa, the Caribbean and Southeast Asia while Britain’s military role ‘east of Suez’ was also abandoned. A sub-phase continued through to the 1980s with independence for various Pacific, Indian Ocean and Caribbean territories and the resolution, for Britain at least, of the Rhodesia/Zimbabwe problem. In 1997 Hong Kong was returned to China.

This is not to say that constitutional change in the empire was neatly confined to the period after the Second World War. After 1931, the so-called ‘Dominions’ – Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the Irish Free State – though retaining an allegiance to the British Crown and associated together as the British Commonwealth of Nations were independent in all internal and external matters. Britain’s most important dependency, India, had also received various doses of internal self-government in the course of the twentieth century, culminating in the 1935 Government of India Act which proposed eventual self-government for India as a Dominion. This was backed up in 1942 by Britain’s promise of post-war independence. Constitutional change in India and the Dominions need not, however, be interpreted as ‘imperialism in decline’ since such changes were calculated to provide the empire with a new ‘streamlined efficiency’, and represented a ‘Third British Empire’ (Darwin, 1980, 1999).

Because strong economic, military, demographic and emotional ties between Britain and the Dominions continued after the Second World War, Hopkins has argued that the withering of this ‘Britishness’ under global pressures should be included in any analysis of the post-war end of empire (Hopkins, 2008). Partly for reasons of space this has not been possible in this short volume. Moreover, Hopkins perhaps overstates his case: Commonwealth unity was fragile even in the inter-war years, with Ireland and South Africa proving particularly difficult bed fellows (and the Free State chose neutrality during the Second World War and as Eire would leave the Commonwealth in 1949) (Murphy, 2009). Meanwhile, Canada’s economic orbit was increasingly that of the United States, and the North American Dominion was outside of the sterling bloc/area (the financial expression of imperial integration). Britain’s ‘great betrayal’ of 1941–2, when the supposedly impregnable colony of Singapore fell to Japan, encouraged Australia and New Zealand to sign a defence pact with the United States in 1951 (Darwin, 2009). Difficulties in coordinating the financial and trade policies of the independent Commonwealth, to suit ‘metropolitan’ needs, encouraged the UK to focus increasingly on the directly administered colonial empire for economic salvation post-1945 (Krozewski, 2001). Indeed, at the end of the Second World War, Britain still lorded over a vast and various set of territories in Asia, Africa, the West Indies, the Pacific and the Mediterranean where moves towards self-government had hardly begun. It is the dramatic diminution of British imperial authority in the colonial empire, rather than the self-governing Commonwealth, in the period after 1945 which is the concern of this book.

Nevertheless, the book does concern itself with a region which was not technically part of the empire, but where Britain was still paramount at the end of the Second World War: the Middle East. The most important territories here were Egypt and Iraq, which by the 1930s had achieved legal independence. But ‘independence’ was subject to Britain retaining effective control over foreign relations and maintaining a military presence because the Suez Canal and the Persian Gulf were regarded as central in defending Britain’s imperial interests in Asia and Australasia. The Middle Eastern territories were not colonies, but constituted, instead, an ‘informal empire’ within the ‘imperial system’ (Darwin, 1988; Ovendale, 1996). As in Africa and Asia, there were attempts to rekindle Britain’s standing in the Middle East after 1945. At the same time, however, British imperial power disintegrated with startling speed in the region.

The term now employed by historians to describe the process of imperial dissolution for Britain (as well as the other European imperial powers) is decolonisation. On a superficial level, decolonisation describes a specific constitutional event marking the transfer of political power from the metropolitan country to the new nation-state (Darwin, 2000). As midnight struck on 30 August 1957, for example, the Union Jack was lowered in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of the Federation of Malaya, and the new flag of the independent state was raised. Later on the morning of 31 August a flamboyant independence ceremony was held where British protection over Malaya was formally withdrawn by the Duke of Gloucester (representing the Queen), and the new Prime Minister of independent Malaya, Tunku Abdul Rahman, read out the Proclamation of Independence (Stockwell, A. J., 1995, III).

But most historians would regard decolonisation as rather more than the simple lowering and raising of flags at independence ceremonies. Two definitions will illustrate this. Hargreaves suggested that decolonisation could be defined as ‘the intention to terminate formal political control over specific colonial territories, and to replace it by some new relationship’ (1996: 3). John Darwin, on the other hand, defined the process as ‘a partial retraction, redeployment and redistribution of British and European influences in the regions of the extra-European world’ (1988: 7). In both these definitions, ‘decolonisation’ is not necessarily synonymous with the ‘end of empire’ or ‘independence’. In seeing decolonisation as a process whereby the economic, political and cultural rules and values of ‘global colonialism’ were superseded by a new international order, Britain’s informal empire of the Middle East is encompassed in our analysis (Darwin, 2000: 7).

Moreover, British policy-makers at the end of the Second World War did not envisage full independence for their colonial and semi-colonial territories. But, in an attempt to revitalise and streamline the imperial system, Britain did attempt to adjust political relationships; a process which ultimately, it could be argued, accelerated and escalated beyond Britain’s control. Decolonisation can thus be seen as a process initiated in London. The next part of this book examines the calculations and recalculations of imperial policy-makers in their attempts to deal with the ‘different and harsher climate’ that eventuated after 1945 (Darwin, 1988: 17).

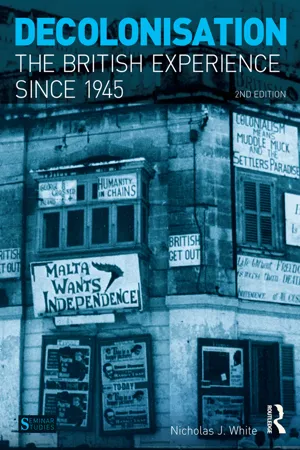

Yet, a focus on the imperial or metropolitan level of analysis might overstate the degree to which the British chose to decolonise. In contrast, an ‘internal’ or ‘nationalist’ approach to decolonisation would focus on the grass-roots developments in the colonial periphery. Indeed, this might seem a far more attractive means of explaining imperial collapse since economic, political and social changes in colonial societies in the course of the twentieth century – culminating in the rise of mass anti-colonial nationalist movements – ultimately meant that Britain could no longer control its empire in the post-war era. The ‘revolting periphery’, it would appear, forced the British to admit defeat and withdraw unceremoniously from one colonial possession after another. The third part of this book seeks to explain the rise of populist nationalism in the British Empire after the Second World War.

On another level entirely, however, it could be argued that what fundamentally brought about the empire’s collapse was the radically changed international political environment after the Second World War. The fourth part of the book analyses the degree to which the emergence of two extra-European and nominally anti-imperial superpowers, as well as anti-colonial international institutions such as the United Nations (UN), squeezed the British out of empire. The final part of the book goes on to assess the British experience in the light of other decolonisations. Generally, the study avoids a blow-by-blow account of decolonisation in the diverse mass of colonial territories which made up the British imperial system. This would be an impossible task in such a concise book. Readers are encouraged to turn to other longer studies, listed in the further reading sections and in the bibliography, for more detailed explanations of events in particular territories. Instead, this book is concerned with unravelling the major themes in, and interpretations of, Britain’s imperial demise.

Further Reading

- J. Darwin’s trio of books, Britain and Decolonisation: the Retreat from Empire in the Post-War World (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988), The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) and Unfinished Empire: the Global Expansion of Britain (London: Allen Lane, 2012), provide authoritative and highly readable overviews of the growth of the British imperial system and its demise. Many an imperial historian has been nurtured by B. Porter’s The Lion’s Share, now in its 4th edition (Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2004). Equally impressive is R. Hyam, Britain’s Declining Empire: The Road to Decolonization, 1918–68 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). For an introduction to the historiographical controversy see J. Darwin, The End of the British Empire: the Historical Debate (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991). A very useful mix of thematic and area studies are the essays in J. Brown and W. R. Louis (eds), The Oxford History of the British Empire: the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).