- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Israel's History and the History of Israel

About this book

In 'Israel's History and the History of Israel' one of the world's foremost experts on antiquity addresses the birth of Israel and its historic reality. Many stories have been told of the founding of ancient Israel, all rely on the biblical story in its narrative scheme, despite its historic unreliability. Drawing on the literary and archaeological record, this book completely rewrites the history of Israel. The study traces the textual material to the times of its creation, reconstructs the evolution of political and religious ideologies, and firmly inserts the history of Israel into its ancient-oriental context.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Israel's History and the History of Israel by Mario Liverani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

A NORMAL HISTORY

Chapter 2

THE TRANSITION (TWELFTH CENTURY)

1. A Multifactor Crisis

Whether positively or negatively influenced by the biblical narrative, modern scholars (archaeologists as well as biblical scholars) have suggested unequivocal yet strongly contrasting theories about Israel’s origins. Even when properly understood as merely one feature in the huge epochal crisis of transition from Bronze Age to Iron Age, the case of Israel continued to receive special attention and more detailed explanation. The historical process has been reconstructed several times, and here it will be sufficient to recall the main theories suggested over the years. (1) The theory of a ‘military’ conquest, concentrated and destructive, inspired by the biblical account, is still asserted in some traditional circles (especially in United States and Israel), but today is considered marginal in scholarly discussion. (2) The idea of a progressive occupation, currently widespread in two variants that are more complementary than mutually exclusive: the settlement of pastoral groups already present in the area and infiltration from desert fringe zones. (3) Finally, the so-called ‘sociological’ theory of a revolt of farmers, which totally prioritizes a process of internal development without external influence; after initial consent during the 70s and 80s this has been less widely accepted, sometimes for overt political reasons. The different theories are usually set one against the other, yet all of them should be considered in creating a multifactored explanation, as required by a complex historical phenomenon.

If we compare Late Bronze Age Palestinian society with that of the early Iron Age, some factors are particularly striking: (1) notable innovations in technology and living conditions, which mark a distinct cultural break and are diffused throughout the whole Near Eastern and Mediterranean area; (2) elements of continuity, especially in material culture, that make it impossible to conclude that this new situation was mostly brought about by newcomers arriving from elsewhere (while real immigrants, the Philistines, display cultural features perfectly coherent with their foreign origin); (3) complementary features in land occupation and use, between a new agro-pastoral horizon of villages and the pre-existing agro-urban system. The resulting competition for the control of economic resources renders plausible some sense of conflict between the two milieus (not necessarily to be read, rather anachronistically, as ‘revolution’).

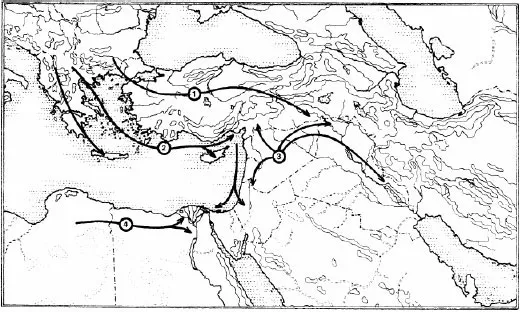

Figure 6. The invasions of the twelfth century: (1 = Phrygians; 2 = Sea Peoples; 3 = Arameans; 4 = Libyans)

If these factors converged at a precise ‘moment’ (let us say, within a century), that is probably due (as historians of the Annales school would say) to the convergence of chronological processes of different duration. There is the longue durée that reveals a recurrence of general settlement patterns, especially in semi-arid zones, caused by changes in the relationship between pastoral groups and urban communities, the ultimate cause being found in climatic changes. Then there are (more rapid) fluctuations in social history, made concrete in technological innovation (in this case evidently crucial), socioeconomic tensions and the evolution of political organization. And finally, the faster rhythm of events, that brings together the complex of factors in a specific moment: and here migrations and political and military events come into play.

The socioeconomic crisis of the end of the Bronze Age stretches back over three centuries (c. 1500–1200). The search for a new order took just as long (c. 1200–900). But between those two sociopolitical and socioeconomic processes of moderate duration falls a brief period of convulsive events, which brings about the final collapse of the already tottering Late Bronze Age society and opens the way for a new order. This violent crisis is concentrated in the first half of the twelfth century, while the transition towards the new order, though quite rapid, takes at least another century.

2. Climatic Factors and Migrations

Following the enthusiastic, positivist historiography of a century ago the idealistic phase has introduced caution in accepting climatic factors as decisive in historical change, since these are beyond human control and thus seen as a mechanical and artificial deus ex machina. The same is true of migration, considered a methodologically obsolete explanation, pointing to the role of ethnic groups, if not races. Today we tend to emphasize socioeconomic processes in accounting for internal evolution and seek to explain the changes in a systemic way, as the working out of variables already in play from the outset.

Though the final crisis of the Late Bronze Age, as we have seen, had all the characteristics of an internal process, we need to recognize that the crucial impulse for the collapse came from outside: a wave of migration, which in turn can be placed in the context of a process of climatic change. In the arid zones of the Sahara and the Arabian desert an intensifying drought was changing broad savannahs into the present day desert. This process peaked around 3000, around 2000, and finally around 1200. Paleoclimatic data are confirmed by historical data: between the end of the thirteenth century and the beginning of the twelfth, a number of Libyan tribes gathered in the Nile Valley. Beginning in the time of Merenptah (c. 1250), and then in years 5 and 11 of Ramses III (c. 1180–1175) actual invasions took place, which the Pharaohs proudly claim to have stopped in epic battles; and the texts record the names of the Libyan tribes that arrived in the Delta, driven by famine to seek pastures and water.

But a series of exceptionally dry years also occurred on the northern shore of the Mediterranean: in Anatolia dendrochronology reveals a cycle of four or five years (towards the end of the twelfth century) of very little rainfall, probably creating a serious famine. In this case too, the historical sources confirm the paleoclimatic data: Hittite and Ugaritic texts mention famines and the importing of cereals from Syria to Anatolia, while Merenptah says he sent wheat from Egypt ‘in order to keep the land of Hatti alive’ (ARE, III, 580). A similar crisis probably occurred also in the Balkans.

As a result, Egypt had to cope with pressure not only from Libyans from the Sahara, but also from the so-called ‘Sea Peoples’, who at first, in Merenptah’s reign, are identified as mercenaries in the Libyan invasion but later, in the time of Ramses III (year 8, 1178), began a wider movement that involved, in clockwise order, all the eastern Mediterranean coast, finally reaching the Egyptian Delta, where it was stopped by the Egyptians in a battle that the Pharaoh celebrates as a huge single victory, but in fact was probably a combined celebration of a series of minor encounters. In describing the arrival of peoples driven by hunger and disorder in their own lands, the Pharaoh records their itinerary, marked out by the collapse of the Anatolian and North Syrian kingdoms:

The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Hatti, Kode, Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya onwards, being cut off at one time. A camp was set up in one place in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Zeker, Shekelesh, Denen and Weshesh lands united. They laid their hands upon the lands as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting… (ANET, 262).

The texts from Ugarit confirm this invasion, though they describe rather the periodical arrival of relatively small groups. An exchange of letters between the king of Ugarit and the king of Alashiya (Cyprus) betrays a deep anxiety over the approaching invaders:

‘About what you have written – says the king of Cyprus to the king of Ugarit – have you seen enemy ships in the sea?’ It is true, we have seen some ships, and you should strengthen your defences: where are your troops and chariots? Are they with you? And if not, who has pulled you away to chase the enemies? Build walls for your towns, let troops and chariots enter there and wait resolutely for the enemy to arrive!’ ‘My father – the king of Ugarit answers – the enemy ships have arrived and set fire to some towns, damaging my country. Does my father ignore that all my troops are in the country of Khatti and all my ships in Lukka? They have not come back and my country is abandoned. Now, seven enemy ships came to inflict serious damage: if you see other enemy ships, let us know!’ (Ug., V, 85–89).

Their concern was probably fully justified, and the consequences were terrible, as the archaeological data show: not only Ugarit and Alashiya, but a whole series of kingdoms and towns of the Aegean, Anatolia, Syria, and Palestine were destroyed and not rebuilt: this means that they were completely abandoned after a total annihilation. The whole political system of the Late Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean collapsed under the assaults of the invaders.

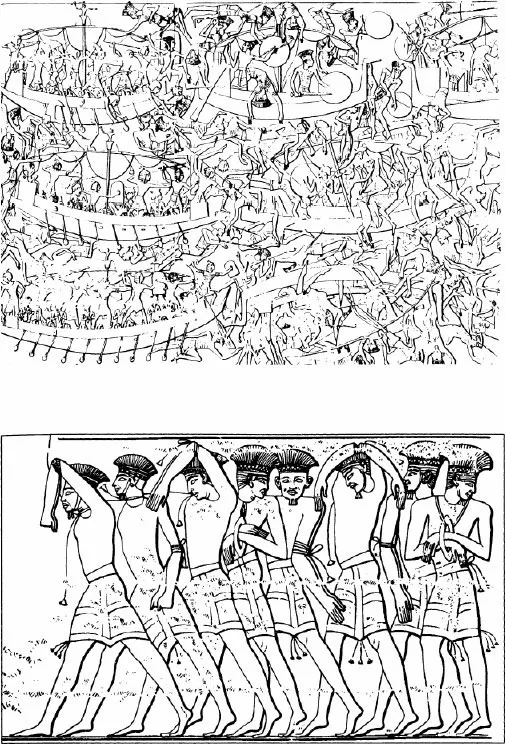

Figure 7. The ‘Sea Peoples’ as depicted by the Egyptians: (a) the naval battle with Ramses III; (b) Philistine prisoners

The protracted socioeconomic crisis, the demographic upheaval, the disdain of the rural population for the fate of the royal palaces, the recent famines, were all certainly factors in the debilitation of Syro-Palestinian society in the face of the invaders. Moreover, these invaders were probably particularly aggressive and determined, with effective weapons (long iron swords) and a strong social cohesion that allowed them to prevail over fortified towns and major political formations. In fact, small groups of ‘Sea Peoples’ were already active on the Eastern Mediterranean coast well before their large-scale invasion – as pirates, and as mercenary troops (the Sherdana, in particular) serving the petty kings of Syria-Palestine but also Libyans and Egypt itself. Those advance guards probably showed their compatriots the way towards those fertile regions richer and much more advanced than those they came from.

Many of the ‘Sea Peoples’, having no prospect of reaching the Egyptian Delta, settled on the Palestinian coast. The most important of these were the Philistines, who occupied five towns on the southern Palestinian coast or its immediate hinterland: Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gath, and Ekron. On the central Palestinian coast, at Dor, according to Wen-Amun’s account, was a settlement of Zeker. It has been suggested (improbably) that the tribe of Dan, settled further north, owes its name (and some of its members) to the Danuna, another of the invading peoples. Once they had occupied or rebuilt the towns, the Philistines established kingdoms on the ‘cantonal’ model of the previous ones, centred on royal palaces. The evidence of external influence, however, is shown in personal names, in inscriptions of an Aegean type (like the tablets found in Deir ‘Alla) and in aspects of the material culture – pottery in particular (first, monochrome Mycenaean III C1, then bichrome, with similar forms but more complex decoration, which is considered typically Philistine), and in distinctive anthropoid clay coffins.

Ashdod, Ashkelon and Ekron have been quite well investigated archaeologically: they all have a phase of initial settlement, exhibiting Mycenaean pottery III C1, and then a fully Philistine phase, with bichrome pottery. Our knowledge of Gaza (probably lying under the modern town) and Gath (probably to be identified with Tell es-Safi) is poor. But the picture is filled out by smaller sites, villages and small towns that replaced the Egyptian garrisons, especially in the northern Negev (see §3.8). At Dor, too, the Iron I settlement is probably to be assigned to the Zeker (the later stratum betrays Phoenician influence). Half a century after the invasion, the towns occupied by the Philistines were again, fully and normally, a part of the Palestinian scenery.

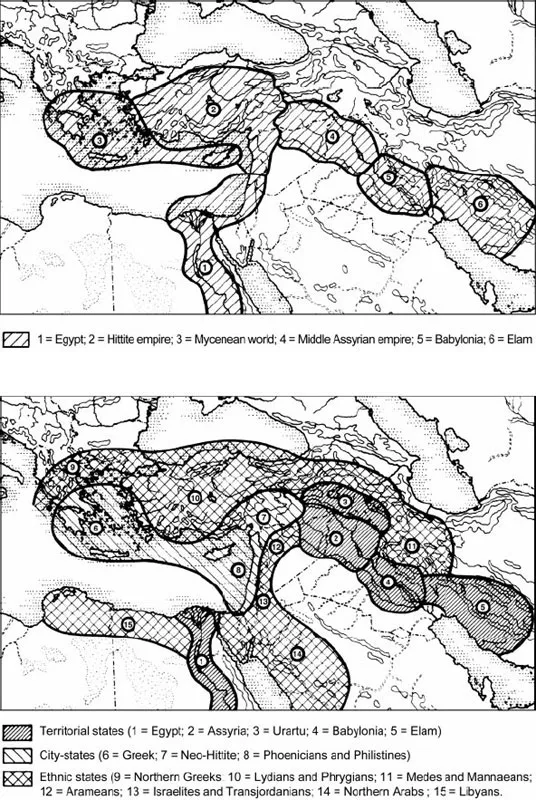

3. The Collapse of the Regional System

The invasion of the ‘Sea Peoples’ had various impacts on the historical fate of Palestine. First of all, it changed the regional political framework of the whole of the Near East bordering the Mediterranean. The two superpowers contending for control of the Syro-Palestinian coastal region, Egypt and Hatti, both collapsed, though in different ways.

The collapse of the Hittite kingdom, which controlled Syria as far as Byblos and Qadesh, was total. The capital, Hattusha, (Boğazköy) was destroyed and abandoned, along with the royal dynasty, and the empire vanished. In Central Anatolia, now occupied by the Phrygians (whose advance forces penetrated during the twelfth century as far as the borders of Assyria), settlements were reduced to tiny villages and pastoral tribes, and a strong cultural regression took place (cuneiform writing and archives disappeared). In the south-east of the former Hittite empire, the kingdoms of Tarkhuntasha (Cilicia) and Carchemish (on the Euphrates) resisted the collapse, and the so-called ‘Neo-Hittite’ states emerged. Some of these (Carchemish for certain) were in fact the direct heirs of the Late Bronze state formations. Though the collapse of the Hittite Empire did not affect Palestine directly, it brought to an end the conflict between Hatti and Egypt that had influenced Near Eastern politics for the preceding centuries (the older state of affairs is still reflected in the expression ‘hire the kings of the Hittites and the kings of the Egyptians’ against one’s enemies [2 Kgs 7.6]).

Egypt’s collapse was less dramatic: the central power absorbed the impact, and victory over invaders from both West and East was solemnly celebrated, as well as newly established peace and internal security. But in fact control over the Libyans was obtained only by ceding them a significant portion of the Delta, where numerous Libyan tribes settled, well beyond the line of fortresses built by the Ramesside Pharaohs. The Sea Peoples, too, could be stopped only by letting them settle en masse on the Palestinian coast, in order to preserve some control over Egypt’s Asiatic possessions. Thutmoses III’s empire in fact came to an end (at least in the terms described in §1.4) after the great battle that Ramses III claims to have won.

Even the powerful Mesopotamian kingdoms of Assyria and Babylonia were reduced to their minimum extent and suffered the invasion of Arameans, who in the ninth and tenth centuries penetrated en masse into the ‘dimorphic zone’ from Northern Syria to the borders of Elam. Thus, Palestine was – for the first time in 500 years – free from foreign occupation and from the menace of external intervention. This situation lasted, as we shall see, until the era of Neo-Assyrian imperial expansion, and encouraged the independent development of a dynamic internal political evolution. ‘Little’ Palestinian kings, accustomed to submission to a foreign lord, were now beholden to no superior authority apart from their gods. So they adapted the phraseology, iconography and ceremony that they had used to show their faithfulness to the Pharaoh, to express their devotion to their city god or national god.

Figure 8. The ‘regional system’ and the crisis of the twelfth century: (a) the system of the thirteenth century; (b) the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Foreword

- Abbreviations

- IMPRINTING

- Part I A NORMAL HISTORY

- INTERMEZZO

- Part II AN INVENTED HISTORY

- EPILOGUE

- Bibliography

- Index of References

- Index of Names of Persons and Deities

- Index of Placenames