- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this updated and extended edition of The Greek Sense of Theatre, scholar and practitioner J.Michael Walton revises and expands his visual approach to the theatre of classical Athens. From the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides to the old and new comedies of Aristophanes and Menander, he argues that while Greek drama is seen now as a performance-based rather than a strictly literary medium, more attention should still be paid to the nature of stage image and masked acting as part of this conception.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Greek Sense of Theatre by J Michael Walton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Theater. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

TheaterPart I

The Athenians and their theatre

1 The critic

STAGE DIRECTOR: The first dramatist understood what the modern dramatist does not yet understand. He knew that when he and his fellows appeared in front of them the audience would be more eager to see what he would do than to hear what he might say. He knew that the eye is more swiftly and powerfully appealed to than any other sense; that it is without question the keenest sense of the body of man. The first thing which he encountered on appearing before them was many pairs of eyes, eager and hungry. Even the men and women sitting so far from him that they would not always be able to hear what he might say, seemed quite close to him by reason of the piercing keenness of their questioning eyes. To these, and all, he spoke either in poetry or prose, but always in action: in poetic action which is dance, or in prose action which is gesture.

Edward Gordon Craig, 19051

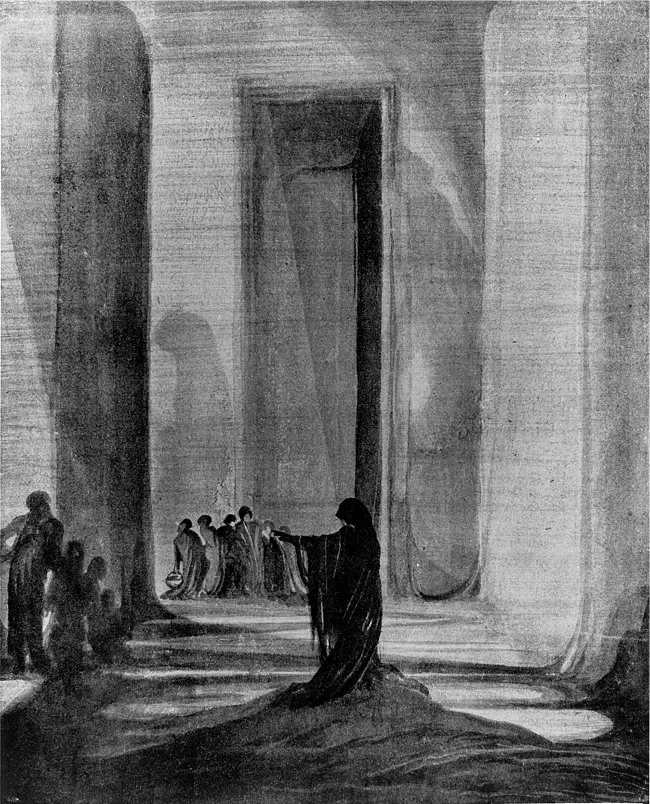

Aeschylus was that first dramatist, and it is one of the theatre’s greater losses that Craig never directed a production of any of his plays. He did create a number of designs for Eleanora Duse as Electra in Hofmannsthal’s adaptation of the Sophocles play, but, as with so much of his work, this got no further than some startling effective drawings (Figure 1.1). The most famous has the downcast figure of Electra with arms outstretched, silhouetted in the foreground against the massive verticals of a doorway upstage. On the steps before the door huddle an indecisive group whose shrinking inaction complements and focuses Electra herself. Craig also made a series of bas-relief black figures, no more than a few inches high, Hecuba and Iphigeneia among them, in which he concentrated the kind of extreme emotion found in the outline of the masked performer. In an earlier passage from The Art of the Theatre Craig claimed the dancer rather than the poet as ‘father of the dramatist’. His remarkable vision of the theatre at a time when the stage was struggling into the twentieth century away from both melodrama and naturalism, found more detractors than converts at the time of writing; his evocation of ‘the theatre of the ancients’, as he called it, even less sympathy within formal classical scholarship.

Figure 1.1 Electra by Edward Gordon Craig, 1913 (Courtesy of the Craig Estate)

In the history of aesthetics the relationship between the aural and the visual had been the subject of discourse for centuries among philosophers and literary critics as well as dramatists. The poet Horace suggested to the budding playwright of Augustus’ time to whom the Ars Poetica is addressed that the eye is ‘a more trustworthy agency’ than the ear, and warned him thereby to be careful about what he showed on stage.2 Gottfried Lessing, often described as the first dramaturg, in his Laocoon (1766) maintained that strong emotions should be ‘displayed’ rather than talked about. And though he asserted that the poet is not compelled, as is the sculptor, to concentrate his description into the space of a single moment, his comprehension of the overlap between artistic forms allows for the complex image that links theatrical tableau to the sculpted figure or the configuration on a red- or black-figure vase.3

The playwright Friedrich Schiller, in his prologue to The Bride of Messina (1803), identified the need for ‘illusion’ in drama and castigated the French neoclassicists for ‘misconceiving the spirit of the ancients’. This requirement, he suggested, depended on the externals of the drama, including the chorus, which defined the open need for artifice where symbol stood for the real.4

Yet somehow the prevailing view of Greek drama handed down from the Roman Empire, through the Enlightenment and into more modern times, is typified by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) where he pronounced that Greek tragedy ‘of course presents itself to us only as word-drama’. But this is absurd. The Greek theatre embodied a fusion of art forms allied to a specific and unique theatrical quality. This may not always be within the grasp of the literary critic, and the mechanics of stage practice in the Greek theatre can be hard to decipher. A further stumbling block, despite Schiller’s reservations, is the persistent attention paid to Aristotle, who, in his Politics and Poetics, appeared to downgrade the performance aspects of the theatre.

Aristotle’s Poetics is widely considered as the founding document of European dramatic theory. After an initial, if problematical, account of the origins of drama, he offers an analysis of the genre of Tragedy and its possible derivation from Comedy. His emphasis on dramatic construction offers a unique view that is valuable and fundamental, but arguably one that has distorted subsequent evaluation of the tragedians of the classical era.

It is hardly the fault of Aeschylus, Sophocles or Euripides that so few of the physical conditions within the Greek theatre were recorded at the time. The dramatists created their plays for a single performance with little, if any, expectation of a second, and only a slim chance of subsequent publication. To discover what the Greeks thought about their theatre, Aristotle tends to be the first port of call. But if Aristotle was the first critic, his claim to the title comes by default. The fifth century BC did not number among its preoccupations the need to capture the present for the sake of the future. Herodotus of Halicarnassus and Thucydides did record aspects of the recent and not-so-recent past for specific purposes, but neither paid more than passing attention to day-to-day affairs in Athens. It was simply not in the brief they set themselves. For any impression of the texture of Athenian life in the fifth century we turn, not to historians, but to the comic playwright Aristophanes and the philosopher Plato. Neither had the writing of social history as an aim; both give away details in passing of public and private concerns and activities. And both had things to say about the theatre. In the absence of any criticism in the modern sense, we can at least gain some impression of how fifth-century Athenians evaluated the theatre of their own time. Different as they may be, both Aristophanes and Plato serve to put Aristotle in perspective.

Aristophanes was a comedian. His plays acknowledge the theatre and glory in its ways. He includes references to the audience, to the settings and to stage machinery which are helpful in recreating both the atmosphere and the details of Old Comedy. He introduces contemporary figures as characters and, if satire may usually be at the expense of veracity, the presence of a stage Socrates or Euripides is at least a tribute to their notoriety. Aristophanes produced Frogs at the Lenaea of 405 BC, only months after the deaths of both Euripides and Sophocles. In a contemporary Athens only a matter of months away from final defeat by Sparta in the Peloponnesian War, Dionysus, god of the theatre, has decided to try and bring back Euripides from Hades to save the dramatic festivals. Arriving on the other side of the river Styx, he discovers that there is no general agreement that Euripides would be the best candidate for resurrection. Dionysus agrees to judge a competition between Aeschylus, dead for over fifty years, and Euripides for the ‘Chair’ of Drama. The competition consists of the two playwrights – Sophocles, who probably died inconveniently with the play already written and in rehearsal, is virtually ignored – making fun of one another’s work and defending their own.

The whole contest is farcical, of course, and the conclusion, which finds Aeschylus rather than Euripides returning to Athens, is on political rather than dramatic grounds – which playwright will give better advice in the current crisis. However, Aristophanes does offer an insight into the style of the two playwrights. In the absence of any alternative view, what is said in the competition has perhaps assumed more weight than it merits, the literal ‘weight’ of lines, in a pair of scales, being a major factor by which Aeschylus is regarded as superior to Euripides. One issue in passing does point towards an important truth.

Euripides complains, among other things, about Aeschylus’ use of the silent figure, sitting with face covered in aspect of grief, saying nothing, while the chorus ‘sets about a cluster of odes’. Aeschylus defends himself and later accuses Euripides of reducing tragedy by the use of unsuitable characters and unsuitable costumes, the often-quoted ‘kings in rags’.5 These sallies are no more than minor aspects of a battle which rages over prologues, over language, over theme and character. Alone they could hardly be used as evidence of the primacy of theatrical elements in the plays. What is important, however, is the admission by Aristophanes, through his characters, of aspects of the theatre that can only be inferred from the scripts. Such references give licence to search out a technique of playmaking that takes account of and, indeed, trades upon such notions as tableau, contrast and stage picture, not as a modern way of viewing ancient plays, but as a part and parcel of the theatre from the beginning.

The Aeschylus and Euripides of Frogs are presumably as fictional as the Aristophanes of Plato’s Symposium, who can offer no contribution at first to the discussion of the nature of love because of hiccups. He subsequently founds his own theory on the belief that man was originally a double being, who was cut in two for his wickedness, each half condemned to pine throughout life for their missing half. The fable serves as light relief for the dinner guests before Socrates contributes a more serious consideration. To a great extent both Socrates and Aristophanes here are Plato speaking.

The same is true of the characters in the Republic, in which Plato offers his formidable opposition to all drama and to the theatre. The Republic is a lengthy treatise in dialogue form on the nature of how to identify ‘dikê’, ‘justice’. A number of minor characters initially offer definitions of justice. Socrates finds each in turn wanting and suggests that it may be easier to approach such an abstract subject by considering first the ideal city-state. After some discussion this it is agreed should consist of three classes, guardians, soldiers and workers, analogous to elements within mankind, as long as these classes are able to work in perfect harmony. Socrates proceeds to consider the education of the guardian or philosopher class and expounds the Platonic ‘Theory of Forms’. It is from this theory that his main reservations about drama stem.

As expounded in the Republic, the Theory of Forms assumes that everything on this earth is an imitation or pale reflection of its ‘Form’ (eidos). At one level the Form of man is God. Physical objects also have Forms. The chair on which you sit, or the table at which you eat, is itself an imitation of the Form of chair or table. The Forms contain within themselves all that contributes to the excellence in any chair or table.

Such an uncompromising doctrine imposes moral problems for the educationalist. Poetry was for the Athenian as much a part of education as reading, writing or physical exercise, but in the ‘ideal state’ it must be the right kind of poetry. Fiction, Socrates argues, means ‘telling lies’. Homer, by presenting gods who cheat and steal, is doubly telling lies. Any dramatic poetry which deals with the gods in a less than favourable light is similarly suspect and should be excluded from the curriculum. Parallel logic is applied to the presentation of a child dishonouring a parent or a hero fearing death. As a result almost any situation occurring in the surviving tragedies and comedies turns out to meet, through the eyes of Plato’s characters, with Plato’s disapproval.

As if this were not enough, the disputants next attack the actor. By a process of strict, if untenable, logic, we are shown that it must be bad for a good man to deviate from his own character to show the audience a bad man. Bad men must not be copied. By a further argument it is agreed that a man can only do one thing best and Socrates is led to the following conclusion:

‘I presume’, he [Adeimantus] said, ‘that the subject at issue is whether we should accept tragedy and comedy into our state, or not.’

‘Perhaps’, I replied, ‘or, perhaps, something more radical still. I do not really know myself. Wherever the argument takes us, there we must go.’

‘Right’, he said.

‘Well then, Adeimantus, should our guardian class be versatile performers [mimêtikoi], or not? Or is it a consequence of what we have already said that each man can only do one job properly, not several? If he attempts several and is a Jack-of-all-trades, he will master none.’

‘What other conclusion can there be?’

‘Is it the same for representation [mimêsis], that a man cannot play many roles as well as he can a single one?’

‘It must be so.’

‘Then he will hardly be able to do anything properly if he can imitate many things and be a versatile performer, since the same man is incapable of working as productively on two forms of imitation [mimêmata] as close as the writing of tragedy and comedy. You did call them forms of imitation, did you not?’

‘I did. It is true. The same man cannot do both.’

‘Nor be a rhapsode and an actor?’

‘No.’

‘Nor actor in comedy and tragedy? These are all forms of imitation, I presume?’

‘Certainly. Forms of imitation.’

‘And, refining human nature further, Adeimantus, it is impossible to act a number of things well, or do well in real life those things of which the acting is an imitation.’

‘Very true’, he replied.

Plato, The Republic, III, 394–95

The argument proceeds that, if a man can represent a bad character on stage without shame, then he cannot be a good man. Why? Because if he were a good man he would not know how to behave as a bad man. Socrates concludes:

Then if a man approaches our state who is capable by his craft of all manner of transformations and can imitate anything and wants to give us a performance, we will prostrate ourselves before him as a wonderful man, a priest, a master of charms. But we will tell him that there is no place within our city for someone like him. We are not allowed to encourage him. And we will pack him off somewhere else after anointing him and crowning him. We will make do with a poet of a more austere kind, who will imitate proper speech and stick to the ideals we propounded when we began the process of educating our soldiery.

Ibid., III, 398

So drama is to be excluded from the ‘ideal state’. But the reasons for its exclusion, though overlapping with the reservations against poetry, are here identified in the person and nature of the actor. Theatre is considered as performance and it is that special nature which makes it, for Plato, so dangerous.

Later, drama comes under attack when Socrates attempts to compose a theory of art. Tragedy is distinguished from epic by mimêsis, ‘representation’. Here, as in other art forms, such as sculpture and painting, artistic achievement is to be judged by likeness to life. Poet and painter imitate life so that artistic creation is at one remove from life; hence second-best. But life itself is, by the Theory of Forms, only second-best to start with. Dramatic representation is twice removed from ‘reality’. This makes it only third-best and the Republic has no use for the third-best.

On one further occasion Socrates and his friends tangle with the theatre when, late on in the Republic, the moral effect of poetry becomes the subject of debate and tragedy is pilloried for exciting in the audience emotions which ought to be kept in check. Socrates to Glaucon:

‘But here is the most serious charge. Dramatic poetry has the most formidable capacity for corrupting almost anybody … Can it be right to admire and gain pleasure from someone on stage, whom we would think unworthy to resemble, indeed be ashamed to acknowledge in real life?’

‘Certainly not’, he replied.

‘And especially if you look at it like this.’

‘Like what?’

‘If you reckon that a playwright encourages indulgence and even pleasure in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Proagôn

- Prologue

- Part I: The Athenians and their theatre

- Part II: The playmakers: Tragedy

- Part III: The playmakers: Comedy

- Epilogue

- Select bibliography

- Index