- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Life of Lines

About this book

To live, every being must put out a line, and in life these lines tangle with one another. This book is a study of the life of lines. Following on from Tim Ingold's groundbreaking work Lines: A Brief History, it offers a wholly original series of meditations on life, ground, weather, walking, imagination and what it means to be human.

- In the first part, Ingold argues that a world of life is woven from knots, and not built from blocks as commonly thought. He shows how the principle of knotting underwrites both the way things join with one another, in walls, buildings and bodies, and the composition of the ground and the knowledge we find there.

- In the second part, Ingold argues that to study living lines, we must also study the weather. To complement a linealogy that asks what is common to walking, weaving, observing, singing, storytelling and writing, he develops a meteorology that seeks the common denominator of breath, time, mood, sound, memory, colour and the sky. This denominator is the atmosphere.

- In the third part, Ingold carries the line into the domain of human life. He shows that for life to continue, the things we do must be framed within the lives we undergo. In continually answering to one another, these lives enact a principle of correspondence that is fundamentally social.

This compelling volume brings our thinking about the material world refreshingly back to life. While anchored in anthropology, the book ranges widely over an interdisciplinary terrain that includes philosophy, geography, sociology, art and architecture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Life of Lines by Tim Ingold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Knotting

1 Line and blob

We creatures are adrift. Launched upon the tides of history, we have to cling to things, hoping that the friction of our contact will somehow suffice to countervail the currents that would otherwise sweep us to oblivion. As infants, clinging is the first thing we ever did. Is not the strength in the new-born’s hands and fingers remarkable? They are designed to cling, first to the little one’s mother, then to others in its entourage, still later to the sorts of things that enable the infant to get around or to pull itself upright. But grown-ups cling too – to their infants, of course, lest they be lost, but also to one another for security, or in expressions of love and tenderness. And they cling to things that offer some semblance of stability. Indeed there would be good grounds for supposing that in clinging – or, more prosaically, in holding on to one another – lies the very essence of sociality: a sociality, of course, that is in no wise limited to the human but extends across the entire panoply of clingers and those to whom, or that to which, they cling. But what happens when people or things cling to one another? There is an entwining of lines. They must bind in some such way that the tension that would tear them apart actually holds them fast. Nothing can hold on unless it puts out a line, and unless that line can tangle with others. When everything tangles with everything else, the result is what I call a meshwork.1 To describe the meshwork is to start from the premise that every living being is a line or, better, a bundle of lines. This book, at once sociological and ecological in scope and ambition, is a study of the life of lines.

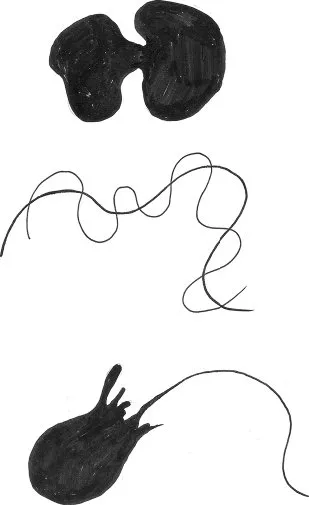

This is not how either sociology or ecology is normally written. It is more usual to think of persons or organisms as blobs of one sort or another. Blobs have insides and outsides, divided at their surfaces. They can expand and contract, encroach and retrench. They take up space or – in the elaborate language of some philosophers – they enact a principle of territorialisation. They may bump into one another, aggregate together, even meld into larger blobs rather like drops of oil spilled on the surface of water. What blobs cannot do, however, is cling to one another, not at least without losing their particularity in the intimacy of their embrace. For when they meld internally, their surfaces always dissolve in the formation of a new exterior. Now in writing a life of lines, I do not mean to suggest that there are no blobs in the world. My thesis is rather that in a world of blobs, there could be no social life: indeed, since there is no life that is not social – that does not entail an entwining of lines – in a world of blobs there could be no life of any kind. In fact, most if not all life-forms can be most economically described as specific combinations of blob and line, and it could be the combination of their respective properties that allows them to flourish. Blobs have volume, mass, density: they give us materials. Lines have none of these. What they have, which blobs do not, is torsion, flexion and vivacity. They give us life. Life began when lines began to emerge and to escape the monopoly of blobs. Where the blob attests to the principle of territorialisation, the line bears out the contrary principle of deterritorialisation (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Blob and line.

Above, two blobs merging into one; middle, two lines corresponding; below, blob putting out a line.

At the most rudimentary level, the bacterium combines a prokaryotic cell with a wisp-like flagellum (Figure 1.2). The cell is a blob, the flagellum a line: the one contributes energy, the other motility. Together, they conspired to rule the world. To a great extent, they still do. For once you start looking for them, blobs and lines are everywhere. Think of the growth of tubers along the tendrils of a rhizome. Potatoes in a sack are but blobs; in the soil, however, every potato is a reservoir of carbohydrate formed along the thread-like roots, and from which a new plant can sprout. The tadpole, from the moment when it wriggles free from its globular spawn, sports a linear tail. The silk-worm, a blob-like creature that, in its short life, expands in volume by a factor of ten thousand through the voracious ingestion of mulberry leaves, spins a line of the finest filament in the construction of its cocoon. And what is a cocoon? It is a place for the larval blob to transform itself into a winged creature that can take flight along a line. Or observe that consummate line-smith, the spider, whose blob-like body is seen to dangle from the end of the line it has spun, or to lurk at the centre of its web. Eggs are blobs of a kind, and fish turn from blobs to lines as they hatch out and go streaking through the water. The same is true for nestling birds as they take to the air. And the foetal blob of the mammalian infant, attached to the interiority of the womb by the line of the umbilical cord, is expelled at birth only to reattach itself externally by clinging digitally to the maternal body.

Figure 1.2 Transmission electron micrograph of the bacterium Vibrio parahaemolyticus.

The rod-shaped cell body is 0.5–0.75 microns wide and on average around 5 microns in length. The flagella are about 20 nanometres in diameter. The size bar at the top right of the picture indicates 1.5 microns. Image courtesy of Linda McCarter and the University of Iowa.

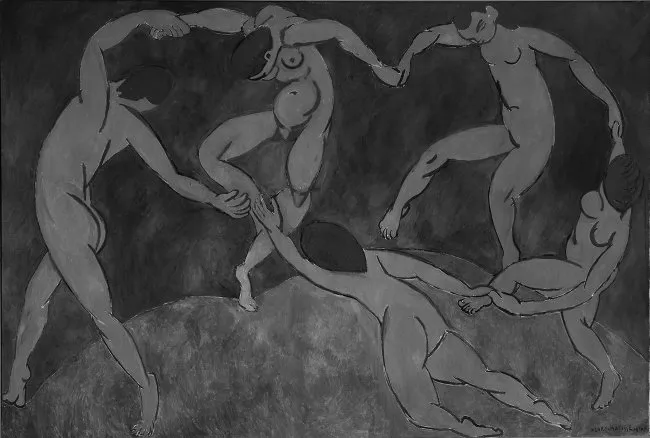

And people? Children, as yet unfettered by the representational conventions of adulthood, often draw human figures as blobs and lines. The blobs endow them with mass and volume, the lines with movement and connection. Or take a look at this celebrated painting by Henri Matisse, Dance (Figure 1.3). Matisse had a very blob-like way of depicting the human form. His figures are voluminous, rotund and heavily outlined. Yet the magic of the painting is that these anthropomorphic blobs pulse with vitality. They do so because the painting can also be read as an ensemble of lines drawn principally by the arms and legs. Most importantly, these lines are knotted together at the hands, to form a circuit that is perpetually on the point of closure – once the hands of the two figures in the foreground link up – yet that always escapes it. The linking of hands, palm to palm and with fingers bent to form a hook, does not here symbolise a togetherness that is attained by other means. Rather, hands are the means of togetherness. That is, they are the instruments of sociality, which can function in the way they do precisely because of their capacity – quite literally – to interdigitate. For the dancers, caught up in each other’s flexion, the stronger the pull, the tighter the grasp. In their blob-like appearance, Matisse gives us the materiality of the human form; but in their linear entanglement, he gives us the quintessence of their social life. How, then, should the social be described?

Figure 1.3 Henri Matisse, Dance (1909–10).

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph © The State Hermitage Museum; photo by Alexander Koksharov.

One way of putting it would be to say that this little group is both more and less than the sum of its individual parts. It is more because it has emergent properties, most notably a certain esprit de corps, that can come only from their association. It is less because nothing in particular has prepared them for it. The association is spontaneous and contingent. Thus while every one of the dancers trails his or her personal biography, much of this is lost or at least temporarily held in abeyance in the exhilaration of the moment. Social theorists have taken to using the word assemblage to describe such a group.2 As a concept, the assemblage seems to provide a convenient escape from the classical alternatives of having to think of the group either as nothing more than an aggregate of discrete individuals or as a totality whose individual components are fully specified by the parts they play within the context of the whole. Yet just as much as the alternatives it displaces, assemblage-thinking rests on the principle of the blob. In place of five little blobs or one big blob, it gives us five blobs that have partially run into one another while yet retaining something of their individuality.3 But whether the parts add up to the whole or not, what is missing from the additive logic is the tension and friction that make it possible for persons and things to cling. There is no movement. In the assemblage, it is as though the dancers had turned to stone.

The theory of the assemblage, then, will not help us. It is too static, and it fails to answer the question of how the entities of which it is composed actually fasten to each other. The principle of the line, by contrast, allows us to bring the social back to life. In the life of lines, parts are not components; they are movements. We should draw our metaphors, perhaps, not from the language of the construction kit but from that of polyphonic music. The dance of Matisse’s painting would be called, in music, a five-part invention. As each player, in turn, picks up the melody and takes it forward, it introduces another line of counterpoint to those already running. Each line answers or co-responds to every other. The result is not an assemblage but a roundel: not a collage of juxtaposed blobs but a wreath of entwined lines, a whirl of catching up and being caught. Not for nothing did the philosopher Stanley Cavell come to speak of life as ‘the whirl of organism’.4 This is an image to which we shall have occasion to return. First, however, we need to take a lesson from a contemporary compatriot of Matisse and one of the founders of modern social anthropology: the ethnologist Marcel Mauss.

Notes

1 I have elaborated on the concept of meshwork elsewhere (e.g., Ingold 2007a: 80–2; 2011: 63–94).

2 See, for example, the ‘assemblage theory’ of philosopher Manuel DeLanda (2006). ‘The autonomy of wholes relative to their parts’, DeLanda argues, ‘is guaranteed by the fact that they can causally affect those parts in both a limiting and an enabling way, and by the fact that they can interact with each other in a way not reducible to their parts’ (2006: 40).

3 A recent contribution from anthropologist Maurice Bloch (2012: 139) offers a particularly clear illustration of this partial melding. Bloch actually adopts the word ‘blob’ as a generic term to cover what other theorists bring under such labels as ‘person’, ‘individual’, ‘self’ and ‘moi’, and even provides a series of diagrams to show how the blob might be depicted. It looks like a solid cone with a sub-conscious core at the base, rising towards a tip of consciousness, over which hovers a halo of explicit representations (Bloch 2012: 117–42).

4 See Cavell (1969: 52). I am grateful to Hayder Al-Mohammad for drawing my attention to this reference.

2 Octopuses and anemones

Textbooks define ecology as the study of the relations between organisms and their environments. Literally surrounded by its environment, and enclosed within its skin, the organism figures according to this definition as a blob. Wrapped up in itself, it takes up space within a world. It is territorial. Sometimes, organisms of the same species cluster together in great numbers, as in the formation of coral, or in the nests and hives of so-called ‘social’ insects. What is often known as a ‘colony’ of conspecifics may be regarded either as an aggregate of discrete organisms or as a single superoganism: it is either lots of little blobs or one big blob. And it was on the foundation of this ecological notion of the superorganic that the discipline of sociology was established by its principal architects: Herbert Spencer in Britain and Émile Durkheim in France. For Spencer, the social superorganism was an aggregate of little blobs: that is to say, a plurality of individuals of the same species, human or non-human, joined by mutual self-interest. It was modelled on the operations of the market. In the market, it is what changes hands that matters, and not the hands themselves. The handshake seals a contract, but is not a contract – an actual binding of lives – in itself. Durkheim, for his part, launched his version of sociology on the back of a polemical critique of the Spencerian market model, above all in the pages of his manifesto for the new discipline, boldly entitled The Rules of Sociological Method and published in 1895. Society, for Durkheim, was one big blob.

There could be no lasting contracts, Durkheim argued, without some kind of warrant that would underwrite the union of otherwise fissile individuals. And this warrant must be sacrosanct; it must lie beyond the reach of individual negotiation. Thus the Durkheimian superorganic was no mere multiplication of the organic; it was, rather, above the organic, situated on an altogether different plane of reality. In a famous passage in the Rules, Durkheim argued that a plurality of individual minds, or ‘consciousnesses’, is a necessary but not sufficient condition for social life. In addition, these minds must be combined, but in a certain way. What, then, is this way? How must minds be combined if they are to produce social life? Durkheim’s answer was that ‘by aggregating together, by interpenetrating, by fusing together, individuals give birth to a being, psychical if you will, but one which constitutes a psychical individuality of a new kind’. In a footnote he added that for this reason it is necessary to speak of a ‘collective consciousness’ as distinct from ‘individual consciousnesses’.1 Aggregation, interpenetration and fusion, however, mean different things, and in listing them one after the other, Durkheim effectively gives us three answers rather than one. So which answer is the right one? Is it by the aggregation of minds, their interpenetration or their fusion that the consciousness of the collective is formed? Or are these supposed to represent three stages, in a process that culminates in its emergence?

Aggregation and fusion, as we have seen, rest on the logic of the blob. Both presuppose that the mind of the individual can be understood as an externally bounded entity, closed in on itself, and divided off both from other such minds and from the wider world in which they are situated. In aggregation, minds meet along their exterior surfaces, turning every such surface into an interface separating the contents on either side. In fusion, these surfaces partially dissolve, so as to yield an entity of a new order – a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. Yet since, in the meeting of minds, that portion that an individual might share with others is instantly ceded to this higher-level, emergent entity, what is left to the consciousness of the individual remains exclusive to its owner. The whole may encompass and transcend its parts, but the parts have nothing, within them, of the w...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Part I Knotting

- 1 Line and blob

- 2 Octopuses and anemones

- 3 A world without objects

- 4 Materials, gesture, sense and sentiment

- 5 Of knots and joints

- 6 Wall

- 7 The mountain and the skyscraper

- 8 Ground

- 9 Surface

- 10 Knowledge

- Part II Weathering

- 11 Whirlwind

- 12 Footprints along the path

- 13 Wind-walking

- 14 Weather-world

- 15 Atmosphere

- 16 Ballooning in smooth space

- 17 Coiling over

- 18 Under the sky

- 19 Seeing with sunbeams

- 20 Line and colour

- 21 Line and sound

- Part III Humaning

- 22 To human is a verb

- 23 Anthropogenesis

- 24 Doing, undergoing

- 25 The maze and the labyrinth

- 26 Education and attention

- 27 Submission leads, mastery follows

- 28 A life

- 29 In-between

- 30 The correspondence of lines

- References

- Index