![]()

A tradition

The workhome has existed for hundreds, even thousands, of years. Examples can be found worldwide, from the Japanese machiya to the Malaysian shop-house, the Iranian courtyard house to the Vietnamese tube house, the Lyons silk-weaver’s atelier to the Dutch merchant’s house. Taking different forms according to culture and climate, workhomes are often so familiar that they are no longer noticed.

Their history has not previously been pieced together, but it can be found, fragmented and often disguised, in publications about houses or workplaces, about individual buildings or architects’ œuvres, or about particular geographical locations or periods of time.1 While an encyclopaedic approach to assembling this history would be valuable, this is not the place for it. The aim of this book is to establish the existence of this building type and to consider its contemporary relevance and potential. So a more limited approach will be adopted here. A small number of examples, all vernacular buildings, will be used to trace some aspects of the history of this overlooked building type from the Middle Ages to the present day, as a way of establishing its existence.

England

There was little differentiation between domestic and productive work in medieval England. Most people inhabited workhomes.2 Lifestyles varied radically according to social status, however, and the buildings of the time reflected this. A snapshot of mid fourteenth-century life in England includes three typical workhomes: the longhouse, the merchant’s house and the manor house. These buildings were sometimes transformed according to activity, time of day or night, or season, and sometimes accommodated the separate functions of dwelling and workplace in distinct spaces.

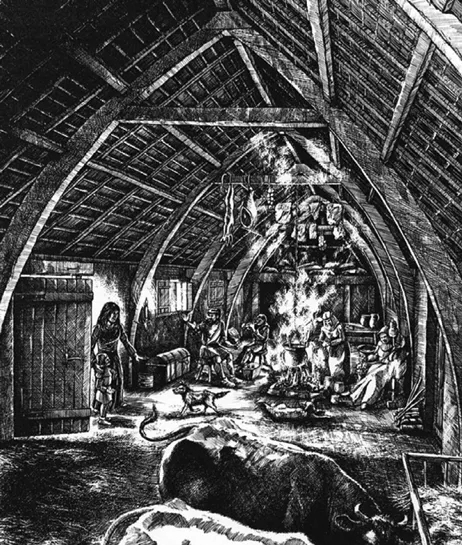

The longhouse was both home and workplace to peasant families in areas of rural England where animals had to be kept indoors at night and in the winter. Single-storied and built from local materials, it consisted of a single open-plan space with animals living at one end and people at the other, separated only by a cross-passage. By sharing the peasants’ space, the animals were protected from predators and extremes of cold; the warmth of their bodies contributed to the peasants’ comfort. All the activities of daily life, including cultivating the ground, tending animals, spinning wool, weaving and making clothing from the wool of their sheep, making leather from the hides of their cattle, preserving food for the winter months, cooking, cleaning and looking after their children, were woven seamlessly together in and around this single space. Figure 1.1 is based on the excavation of a cluster of longhouses in a medieval village, Wharram Percy in North Yorkshire, which was deserted shortly after 1500. It shows a reconstructed interior combining kitchen and spinning/weaving/dressmaking workshop, bedroom and dairy, dining room, butchery, tannery and byre. Peasants’ lives were structured by the seasons, the weather, and the rhythms of day and night, as well as by the need to work for the local lord to pay the rent and to attend the Manor Court. Despite an obligation to their landlord, the villagers lived and worked in a state of relative autonomy, cultivating the fields surrounding their workhomes collectively and exercising control over many aspects of their lives.3

FIG. 1.1 Reconstruction of daily life in a medieval longhouse in the deserted medieval village of Wharram Percy, North Yorkshire

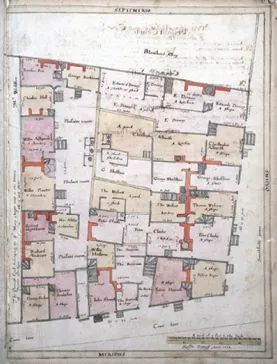

The tall, tightly packed townhouses of medieval England also integrated workspace with living accommodation. Ralph Treswell, an early seventeenth-century map-maker, drew surveys of a series of London buildings, medieval in layout and crammed together in tenements, that show that even the smallest tended to have a ground-floor shop, workshop, warehouse, inn or bake-house, and living spaces above [Fig. 1.2]. Individual craft workers inhabited workhomes like this, clustered together on the streets of market towns, in which they made, stored and sold their goods. The form and inhabitation of these buildings continued virtually unchanged for centuries. Samuel Pepys was born in 1633 in one, his father’s tailor’s shop. The household, his biographer Claire Tomalin tells us, centred on the ground-floor shop and cutting room, a rear kitchen opening onto a yard: ‘… older children, maids and apprentices slept on the third floor … or in the garret, or in trundle beds, kept in most of the rooms, including the shop and the parlour; sometimes they bedded down in the kitchen for warmth’.4 Domestic life was also inextricably entwined with the business of trade in the medieval merchant’s house. The much-restored example at 58 French St, Southampton, was built for a wealthy thirteenth-century wine merchant [Fig. 1.3]. It was entered through a narrow entrance passage that led past a shop where goods were displayed. Passers-by were served over a fold-down counter that acted as a shutter when not in use, protecting the building from theft and bad weather and indicating when the establishment was closed for business. The front shop and rear counting house, where the merchant made his most important transactions, opened off a large central, semi-public double-height space (the ‘hall’), where customers were offered hospitality and meals were eaten. Family and guests slept in small front and rear first-floor rooms. Trading and family life, public and private, were integrated in this workhome in a way that is generally unfamiliar in twenty-first-century England. The unglazed shop was part of the street, but also part of the home; the business of selling involved the whole family. The main living room was a workspace where business was carried out and customers entertained, but also the space where children played and meals were prepared. The rear room where deals were struck was a comparatively informal domestic-scale space, to a contemporary eye a far cry from the corporate office.

FIG. 1.2 Ralph Treswell survey plan, Cowe Lane, London, 1612

FIG. 1.3 Cutaway drawing of medieval merchant’s house at 58 French St, Southampton

Work and life were similarly undifferentiated in the manor houses of the English medieval gentry. Fourteenth-century Penshurst Place in Kent, inhabited over generations by a lord of the manor, his family, guests and household of employees, was built to the standard ‘H’ plan of the time. Its immense central double-height hall is sandwiched between two two-storey wings that contain a series of smaller spaces, little altered despite centuries of extensions. All members of the household, from the most menial to the most powerful, lived and worked in and around this building, the two activities generally being indistinguishable. The work of the lord of the manor revolved around the maintenance of his ‘honour, status, profit and wellbeing’,5 and involved keeping a huge household and offering extensive hospitality. Some 519 people, including 319 guests, sat down to lunch at Epiphany at Thornbury Castle (an equivalent establishment to Penshurst) in 1508, and 400 to supper.6 The list of foods consumed at this event indicates the scale and splendour of the feast:

… from the lord’s store: 36 rounds of beef, 12 carcasses of mutton, two calves, four pigs, one dry ling, two salt cods, two hard fish, one salt sturgeon. In achats [i.e. purchased]: three swans, six geese, six suckling pigs, ten capons, one lamb, two peacocks, two herons, 22 rabbits, 18 chickens, nine mallards, 23 widgeons, 18 teals, 16 woodcocks, 20 snipes, nine dozen great birds, six dozen little birds, three dozen larks, nine quails, half a fresh salmon, one fresh cod, four dog fish, two tench, seven little breams, half a fresh conger, 21 little roaches, six large fresh eels, ten little whitings, 17 flounders, 100 lampreys, 400 eggs, 24 dishes of butter, 15 flagons of milk, three flagons of cream, and 200 oysters. Together with 678 loaves of bread, 33 bottles and 13 and a half pitchers of wine and 259 flagons of ale (20 of which were drunk by the gentry for breakfast…).7

Armies of peasants worked in the fields to provide the basic ingredients, and swarms of servants in the kitchens to prepare such a feast. Brewing and baking on a huge scale were continuous processes. The noble family and their most important guests sat for meals on a raised platform at the end of the hall, looking down on rows of tables where the other members of the household ate. The lavish food and drink were served from small rooms near the kitchen, separated from the main building to minimize hazard from cooking on an open fire. Served with great pomp and ceremony, these feasts were followed by entertainment from minstrels, strolling players, jugglers or jesters. At night the servants cleared away the trestle tables and the household slept on the rush-covered floor around the fire i...