![]()

1

Fundamental Principles of Supervision

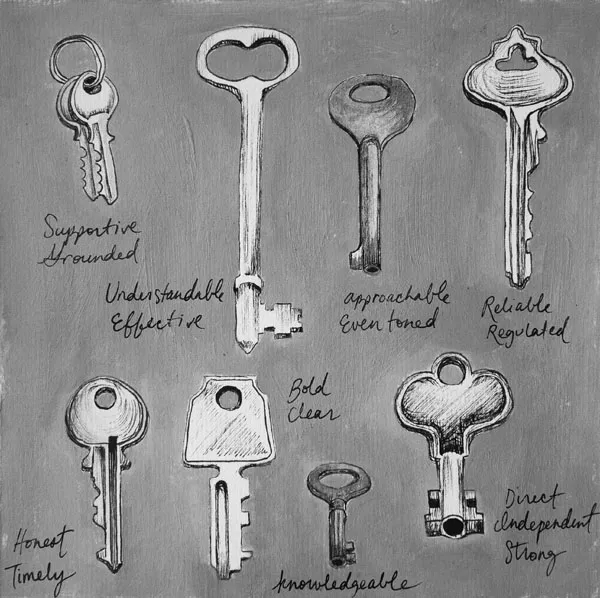

Keys to Supervision

A therapist I supervised for some time came to see me because she was struggling with her new role as an administrator in a day treatment program for adults with chronic mental illness. As we talked about her efforts to find her personal style for supervising the staff, she began painting a hand holding a key. When she returned the following week to resume our discussion, she brought another image, Keys to Success (Figure 1.1). She painted this image at home after supervision as she continued to explore her concerns.

The therapist’s watercolor and ink painting depicted an array of keys that she labeled with the skills that she thought were necessary to effectively supervise others. The image was her “key” to recalling and accessing her own strengths, supporting her successful work with those in her charge. As we painted and talked together, she worked to recognize that she had the qualities that she needed. Her challenge was one of finding confidence and remembering to believe in her own abilities.

There are parallels between the work of therapy and that of supervision (Wilson, Riley, & Wadeson, 1984). Both are intimate relationships with important boundaries and guidelines. This chapter provides fundamental information to clarify expectations for supervisors, those who are considering supervising in the future, and for supervisees wanting to understand what to expect from this important relationship.

Supervision is a form of support and oversight that is provided in all mental health professions. Beginning in training, we learn to rely on a colleague with more experience to guide and direct our work. Seasoned practitioners often revisit supervision throughout their careers to ensure the clarity of their practice. As professional relationships evolve, former students become supervisees, colleagues, and often friends. I am happy to say that those who helped me find my way as a therapist early in my career continue to be resources for me to this day.

FIGURE 1.1 Keys to Success

Supervisor Training

There are some aspects of supervision that come naturally. Reflecting on his or her own early work, the advanced clinician can empathize with the new therapist’s experiences. As a supervisor it is gratifying to support earnest work to understand the complexity of treatment planning, explore interpersonal dynamics, and investigate the systemic issues that have impact on treatment. However, there are responsibilities in this multifaceted practice that may be less evident to the new supervisor. The evaluative component, intrinsic in supervision, requires accountability for the quality of care provided by the new therapist to the client and the agency where he or she provides services. This calls for the supervisor to be firm as well as supportive when addressing supervisory issues, compliance with policies and procedures, and standards of practice.

In the past, therapists have taken on supervisory roles with only their own experience as a guide. Recently many professions, such as counseling, have begun to include supervisory coursework as part of their degree requirements. State credentialing boards have begun to require the acquisition of formal supervisor training to maintain licensure. Some organizations monitor experience, training, and years of supervisory practice as well as offer advanced certification for “master” supervisors. Training opportunities can address the challenges and complexities of this role and offer guidance on how best to provide support for the ongoing quality of care for clients.

Literally meaning “to oversee,” supervision entails a complex set of skills; whether acquired formally, through experience, or intuitively, these skills can be sharpened. Supervisors may take advantage of seminars and other training opportunities offered through formal education programs and local and national professional associations as a way to develop a keener skillset.

Professional Credentials

It is the supervisor’s responsibility to guide the new therapist through professional requirements and milestones, providing information about expectations and helping him or her to become a professionally sound, informed consumer of supervisory services. When working with those in graduate training, the supervisor must be knowledgeable and able to inform students about the training guidelines and postgraduate qualifications established for programs that are approved by their corresponding professional associations and credentialing bodies.

Many programs that provide training are approved or accredited and regularly reviewed by their corresponding professional associations or state licensing boards to ensure ongoing compliance with guidelines established to assure the quality of training and best practices. During graduate school, the expectations for site and faculty supervision are regulated, including the credentials of the supervisors, size of the fieldwork class, and number of hours spent weekly with clients and in supervision. As the requirements for credentials vary from state to state, supervisors should direct individuals considering training to contact their state and national professional associations in the location where they intend to practice to ensure that the educational program they choose meets the required educational standards.

After graduation, during the early years of professional practice, new therapists seek supervision as they work toward professional credentials and licensure. A supervisor who is well versed in the specific discipline’s requirements in the state of intended practice can facilitate the navigation of these specialized milestones.

The qualifications for obtaining credentials vary by professional discipline and location. For example, art therapists are credentialed through national regulation and may be licensed according to the state. Graduates from art therapy training programs that are approved by the American Art Therapy Association (AATA) may apply for art therapy registration (ATR) and board certification (BC) with the Art Therapy Credentials Board (ATCB) after one thousand supervised postgraduate art therapy contact hours. Graduates from unapproved programs must complete two thousand supervised postgraduate contact hours to earn the ATR.

License titles, qualifications, and training requirements vary from state to state as do the requirements for supervisors. New therapists should confirm that their selected supervisor has current, appropriate credentials in order to ensure that their supervision hours qualify them for their own credentials.

There are also discipline- and location-specific guidelines for the ways new therapists may gain postgraduate experience. Depending on state law, working as a consultant is often prohibited until the clinician is a licensed professional. Until that time, the therapist must accumulate the hours required for licensure by working as an employee of an agency. This is intended to protect the public. A consultant is an independent contractor that is paid on an hourly basis and is responsible for his or her own liability. Most often as a credentialed professional, the consultant has years of postgraduate, supervised experience in preparation for independent practice. As an employee, the new therapist is held responsible for following the agency’s policies, procedures, and practices while working under the oversight and supervision of the agency. Some professions count hours of volunteer experience toward credentialing as long as a credentialed professional provides the supervisee with supervision; others do not.

Supervisory Functions

Supervisors are gatekeepers and guides, overseeing the quality of client care and facilitating new therapists’ professional development. While managing the work of new therapists, the two main functions of supervision are clinical and administrative. These tasks are not mutually exclusive. The supervisor guides and evaluates the work, ensuring sound practice and overseeing the documentation of services. The supervisor provides support, direction, and evaluation while ensuring adherence to professional standards. At the same time he or she is an ally, supporting and advocating for the new therapist within the agency.

Clinical Supervision

Clinical supervision focuses on the nuances of working with clients and new professionals’ unfolding understanding of therapeutic practice. Here the supervisee brings information about his or her work, discussing what transpired in order to reach a deeper understanding of the services provided. The overarching goal of this aspect of supervision is fostering ethical and effective clinical work. The focus of clinical oversight varies widely. One strategy is to take a broad view that allows for the examination of questions or crises that have arisen since the previous session. A more in-depth approach may track a single challenging case or group over a period of time. Whatever the strategy, it is best that the participants agree upon a method that is suitable to the supervisee’s needs in order to maintain a constructive focus. This approach should be evaluated periodically as skills and needs evolve.

In addition to the planning and interventional components of clinical work, relational issues are a key dimension of mental health practice. Countertransference and other personal responses to clients and coworkers are frequently encountered in the course of treatment. Helping supervisees to unravel these challenges can remove interpersonal impediments and bring clarity. While this facet of clinical supervision comes closest to therapy, it is this very closeness that necessitates sensitive exploration of issues of power and cognizance of professional boundaries.

Supervisory oversight takes different forms. For example, in art therapy training supervision is provided from two vantage points, those of the field site supervisor and the faculty supervisor. Within this paradigm, the field site supervisor has the proximity to observe treatment directly. With firsthand experience of clients and the setting, this supervisor can be an essential resource for support, feedback, and direction. The faculty supervisor provides oversight within a class format, helping students understand what to expect from supervision and facilitating their application of academic content to real-world practice. In this forum, student therapists engage alternative perspectives and are exposed to work with a wide range of client, systemic, and interpersonal concerns encountered in the field.

These ways of working may be replicated after graduate training. Some new therapists participate in supervision on-site that may focus on administrative and clinical issues that arise in treatment. Many seek additional supervision from a professional outside of the agency to supplement and deepen their understanding and skills, supporting their professional goals. This is often the case for new art therapists when there is not a senior art therapist employed on-site. In fact, art therapists must receive supervision from a registered art therapist for at least half of their postgraduate hours to qualify for their own registration as an art therapist.

This is one profession’s model of supervision. Others vary by discipline and have corresponding requirements for oversight. Working across disciplines has advantages. However, the development of competency in a professional scope of practice and appreciation of clinical nuances may be best supported by someone working within the same paradigm.

Administrative Supervision

Administrative supervision focuses on the communication of information and assures that professional standards of practice and agency policies and procedures are followed. Schedules, budgets, and projects are discussed, feedback is provided, guidelines are communicated, documentation is reviewed, and performance evaluations are conducted. While therapists are in training, the field site supervisor plays a central role in providing administrative direction, introducing the new therapist to the agency, supporting his or her evolving working relationships, helping to mediate conflict, and facilitating successful work with others. After graduation, new therapists working in agencies are typically assigned to a specific staff member who provides administrative supervision. This same person may or may not provide clinical oversight.

Supervisors are role models, demonstrating professional engagement with colleagues. They guide new therapists’ professional development as well, promoting involvement in professional organizations, encouraging new therapists to seek peer support and other resources on- and off-site, and supporting participation in continuing education, conferences, and other professional activities. The supervisor recommends readings, training opportunities, and conferences related to practice and often gives advice regarding career choices and professional credentials. The supervisor is typically called upon to play a formal role in documenting clinical performance as a part of licensure or other credentialing processes.

Scope of Supervision

The open discussion of expectations supports sound supervision during therapist training and postgraduate work. To clarify this complex relationship, it is critical to have an understanding of mutual responsibilities, establishing a supervisory agreement that delineates what each person can anticipate from this unique relationship.

When an intern is placed at an agency during training, a supervisory agreement is made between the academic institution and the fieldwork site. This written document clarifies roles and expectations for the intern, the school, the supervisor, and the agency. It reflects the supervision partnership between the school and the agency and establishes parameters for the frequency and duration of supervision and the key responsibilities of the site supervisor, the faculty supervisor, and the intern. This agreement clarifies the student’s academic schedule and the requirements for internship hours. It specifies methods for evaluation and observation and includes the forms and a schedule for written evaluations. It also delineates the expectations for the duration and frequency of on-site supervision.

Professionals providing postgraduate supervision should develop their own written agreement, delineating mutual expectations and spelling out parameters for their work. This document includes specifics such as the time and structure of meetings, fees and cancellation policy, the method and frequency of evaluation, and the limits of confidentiality. It conveys the supervisor’s training and credentials, specifies areas of competencies, identifies the supervisor’s theoretical approach, and provides contact information in the event of a complaint. Discussing this agreement helps new therapists to appreciate the importance and complexities of the informed consent process that they engage in with clients.

Postgraduate professionals and those in training are expected to follow the professional ethics and standards of practice of their discipline as well as the day-to-day policies and procedures of the agency where they work with guidance from the supervisor. These include clinical procedures for reporting recipient abuse or neglect, policies regarding the dress code, and expectations for calling in sick and scheduling time off. The supervisor is responsible for the new professional’s practice. He or she is charged with ensuring the client’s well-being by guiding, managing, evaluating, and communicating critical feedback to the supervisee about his or her work. The effective transmission of expectations is critical. For that reason, individual learning goals...