![]()

An introduction to a growing cross-disciplinary field, Literature and Food Studies examines genres and rhetorical traditions that chronicle the local conditions and global migrations of cuisines, commodities, and agricultural systems. These literary engagements with the edible world demand complex ways of thinking about food because they interlace its cultural and corporeal meanings and move across the scales at which those meanings take shape. As works of literature interact with food in its various stages—agricultural, culinary, and alimentary—they often traverse the boundaries between the intimate and the social as well as the microscopic and the planetary, a capacity that arguably defines the literary. It is this capacity that makes literature an especially vital and vibrant area of inquiry for food studies. Put differently, we view the relationship between literary practices and food practices as recursive. Literary texts do not just transmit or depict food cultures and food practices: they also help to structure them. Through this lens, Literature and Food Studies discusses works of imaginative literature, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale to James Joyce’s Ulysses and Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby, alongside what we define as food’s vernacular literary practices—practices that take written form as horticultural manuals, recipes, cookbooks, restaurant reviews, agricultural manifestos, dietary treatises, culinary guides, and more.

In making the case for a food studies approach to literature and a literary approach to food studies, the chapters that follow compare literary forms and practices that center on matters of food in order to explore how they illuminate and, at times, obfuscate histories of colonialism and communalism, labor and leisure, scientific research and creative production, ethical consideration and environmental degradation. Throughout the book, food entails a complex terrain of social and biophysical systems. In the case of chocolate, for instance, these systems encompass the propagation of sugarcane and cacao; the violence of the Middle Passage and plantation slavery; ancient and contemporary trade routes that crisscross the globe; the persistence of human trafficking in the twenty-first century; and the habits, tastes, and rituals that have inspired and been inspired by prepared chocolate, from the Aztec and Spanish empires to multinational candy corporations and fair trade cacao farms.

For those new to our subject, Literature and Food Studies offers three things: it introduces core concepts that have become central to food studies since the field’s emergence decades ago within cultural anthropology, geography, and history; it compares oft-read literary texts with forms of writing and print culture that rarely are taught in literature classrooms but that resonate with the organizing questions and concerns of food studies; and it aims to inspire future research and teaching. Considering a wide range of materials, Literature and Food Studies ultimately demonstrates that desires to cultivate, procure, prepare, taste, and ingest certain foods and not others stem not only from political realities and ethical considerations that food writing depicts but also from appetites that writers have whetted.

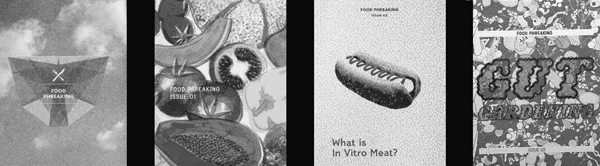

A contemporary example helps to illustrate the approaches and arguments that Literature and Food Studies develops: namely, a self-published, small-format magazine (or “zine”) called Food Phreaking [sic] that a playful collective of artists and writers known as the Center for Genomic Gastronomy (CGG) began producing in 2013 (see Figure 1.1). Akin to other print works that CGG has created, Food Phreaking draws from multiple genres, including the artist book, environmental manifesto, and scientific catalog. In doing so, the zine documents what the authors of the 2016 issue call “experiments, exploits, and explorations of the human food system” and thus galvanizes new networks of “farmers, foodies, hackers, artists, and scientists” (Russell et al. 1). The inaugural issue takes the form of thirty-eight vignettes, each composed around a striking image and humorous snippet of text and then tagged in one of four conceptual categories: “A: Legal and Open,” “B: Illegal and Open,” “C: Illegal and Closed,” and “D: Legal and Closed.” At first blush, these categories embody current conflicts between, on the one hand, industrialized agriculture and agribusiness, and, on the other, the principles that organic farmers and food activists support. However, a close reading of the whimsical design and eclectic vignettes of Food Phreaking reveals a vision that does not fit neatly into either of these frameworks. Instead, the vignettes invite readers to imagine food systems of the future that mix the synthetic with the organic, the ancient with the new. Food Phreaking not only invokes patented transgenic seeds, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and branded products like Kraft cheese, but also offers a high-tech recipe for cooking beet peels, a sketch of raw milk vending machines in Europe, and, most provocatively, an anecdote about CGG’s own use of genetically engineered “GloFish” (originally made for decorative aquariums) to prepare sushi for an event at which a dinner party melded with performance art. These examples capture what CGG means by the term “food phreaking” itself, as a practice that bridges different types of experimentation toward the goal of creating both new stories and new systems for producing, procuring, preparing, and interacting with food in the future.

Our analysis of Food Phreaking highlights another key premise of Literature and Food Studies. We contend that food studies invites a redefinition of the objects of literary study to include not only poetry, drama, and narrative—the three major forms of literature with a capital “L”—but also what we term vernacular literary practices. By this term we mean quotidian modes of writing that develop within specific historical contexts and that intermix rhetorical and aesthetic craft with the dissemination of applied knowledge that is variously empirical, sensory, instructive, interactive, and intergenerational. Genre—a core concept for literary studies—provides a crucial analytical framework for the study of these vernacular literary practices, which take textual form as, most notably, recipes, cookbooks, gardening primers, culinary memoirs, dietary advice essays, agricultural handbooks, protest writings about hunger, and, finally, what Bruce Robbins terms “commodity histories” of storied foods like chocolate, sugar, and saffron. These vernacular genres are at once creative and practical, and they have often intermingled with so-called “high” literature. This intermingling is evident, for instance, in the influence of horticultural handbooks (known as herbals) on Shakespeare’s tragicomedy The Winter’s Tale; in satirical depictions of war rationing and famine on the part of modernist writers such as English essayist and novelist George Orwell and American poet Lorine Niedecker; and in the colonial and postcolonial histories of the food system that contemporary novels by Toni Morrison, Monique Truong, and others trace. These examples speak to our wider aims. We model an approach to literature and food that integrates the methods of cultural history, close reading, and archival research with concepts drawn from both literary studies—such as narrative, rhetoric, form, audience, authorship, and taste—and food studies—such as foodways, food justice, gastronomy, and agrarianism. The book further aims to tease out relationships between cultures of food and major literary forms: tragedy, utopianism, satire, modernist fiction, and so on. Following Kyla Tompkins, David Goodman, E. Melanie DuPuis, and others, we see these aims as part of critical food studies—a rubric that scholars in the humanities and qualitative social sciences have adopted to signal at once cultural approaches to and critical distance from the food habits, systems, and discourses they study (DuPuis; Goodman et al.; Tompkins, “Consider”; Tompkins, Racial Indigestion).

Literature and Food Studies is not, however, a comprehensive literary and historical survey. Rather, the book orients readers to the field of critical food studies through five illustrative cases, which investigate in turn (1) myths of seasonality and the Edenic garden in ancient and early modern literature, (2) utopian, polemical, and satirical discourses of dietary and agricultural reform running from the sixteenth century through the Industrial Revolution, (3) Aztec chocolate recipes and their colonial migrations and markets, (4) meals, memory, and the formal operations of eating in modernist fiction, and (5) the roles of authorship and print culture in the transnational history of gastronomy and culinary writing. The first of these chapters, “Food routes: seasonality, abundance, and the mythic garden,” addresses imperial tropes of seasonality and abundance, especially as they surface in the household manuals, horticultural writings, and Shakespearean drama of early modern England. The next chapter, “Virtuous eating: Utopian farms and dietary treatises,” traces a rhetoric of dietary virtue within transatlantic literary culture—from Sir Thomas More’s sixteenth-century prose work Utopia to modern manifestos on vegetarianism—comparing these texts to Louisa May Alcott’s satire of the failed Fruitlands communal farm and Benjamin Franklin’s wry narrative of lapsed vegetarianism in his Autobiography. We focus again on the early modern period in “Recipes as vernacular literature,” which considers the Aztec, Spanish, and North American sources of chocolate recipes. Here, we put the gendered facets of recipe writing—a pathway for aristocratic and eventually middle-class women to become authors—into conversation with histories of agricultural labor in both colonial and postcolonial contexts. Turning to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, we analyze forms of narrative that scenes of eating engender in modernist and contemporary novels in “Gustatory narrative: meals, memory, and modernist fiction.” Our final chapter, “Authoring gastronomy: professional eaters and culinary print culture,” elaborates on prior considerations of cookery, recipes, and culinary writing via a literary history of gastronomy, a largely elite and male-dominated profession that we trace from ancient Greece and China to post-Revolutionary France and contemporary urban centers. The chapter concludes by shifting from the authors who fashioned gastronomy as “the art and science of eating well” to what we term the counter-gastronomical writing of Italian futurist F.T. Marinetti, English essayist and novelist George Orwell, and French novelist Muriel Barbery.

As this chapter outline suggests, the book moves between frameworks central to food studies and those important to literary studies, while often showing that the two overlap in their intellectual concerns and curiosities. More pointedly, the pages that follow engage with theories of gender and sexuality; empire, colonialism, and diaspora; sustainability, ecology, and food justice; and the vexed relationships between humans and other beings—animal, plant, and microbial. As such, the book highlights a cross-disciplinary network of scholars who have helped to establish food studies and its particular purchase for students and scholars of liter...