CHAPTER

1

Mouse Lemurs: The World’s Smallest Primates

Mammals can be spectacular in many ways, perhaps none more strikingly so than in the large sizes they can reach. The African bush elephant, the largest living land mammal, can weigh an impressive seven tons and stands a massive twelve-feet high. Large, conspicuous mammals attract both public and research interest. They are often elevated to flagship status and can be impressive ambassadors for national conservation efforts. Yet most mammals lack impressiveness of size. The great majority measure less than one foot, and their inconspicuousness is often compounded by cryptic and nocturnal habits. Even among primates, which typically are neither small nor nocturnal, there are species that combine these traits. Mouse lemurs, which weigh approximately 25–110 g, are the world’s smallest living primates (Atsalis et al., 1996; Zimmermann et al., 1998; Rasoloarison et al., 2000; Yoder et al., 2000). Small size and nocturnal activity make these and other nocturnal primates fascinating but also a challenge to study. Indeed, for most of primate research history, the study of nocturnal species has been relatively sporadic. In the past, each published paper was a major contribution to our understanding of a lifestyle uncommon within the visually dominated diurnal primate world but not uncommon among mammals at large (e.g., Charles-Dominique, 1971, 1972; Martin, 1973; Petter, 1977, 1978; Charles-Dominique and Petter, 1980; Hladik et al., 1980; Pagès, 1980; Clark, 1985; Harcourt and Nash, 1986a). More recently, noteworthy research findings have advanced considerably our understanding of nocturnal primate behavior and ecology. The application of new or refined technology, such as radiotelemetry, microchips, and genetic analyses, has led to research breakthroughs. The pioneering and curious spirit of research biologists has been the driving force behind our growing understanding of the nocturnal primate world in all its diversity, but underlying the goals and aspirations of scientific research may be a sense of urgency as habitat destruction threatens wildlife worldwide.

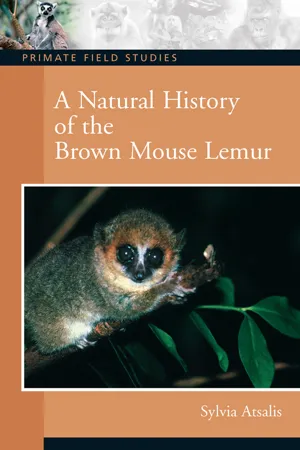

Microcebus rufus, the brown mouse lemur, in Ranomafana National Park.

Are nocturnal primates destined to go “from obscurity to extinction,” as Martin (1995) so succinctly wondered? Perhaps this sad fate will be avoided because even as extinction threatens many primates, long-term studies on nocturnal species are leading the way to transforming our understanding of the order. Advances in our knowledge of nocturnal primates are especially significant on the island of Madagascar, where approximately 60% of primate species are nocturnal. Nevertheless, the fear that the world may lose species to extinction—not only nocturnal lemurs but also other species that comprise Madagascar’s rich natural world—before we discover or become familiar with them is a realistic one. The island’s central plateaus are largely devoid of forest, possibly as a result of anthropogenic activities since occupation took place approximately two thousand years ago (Wright and Rakotoarisoa, 2003). Today, although approximately 90% of the island’s animals live in forests (Dufils, 2003), only small pockets of forests remain hugging the coastal line (Smith, 1997).

In recent years, the island has drawn the interest of biologists keen to discover its unique flora and fauna. Madagascar may be poor in diversity of diurnal mammals (Goodman et al., 2003) and birds (Hawkins and Goodman, 2003), but it is rich in reptiles (Raxworthy, 2003) and amphibians (Glaw and Vences, 2003). Notably, 84% of all land vertebrates there are endemic (Goodman and Benstead, 2005). For those interested in primate behavior, Madagascar boasts intriguing attractions: the country ranks among the highest in the world in primate diversity (Mittermeier et al., 1994); all primates on the island are found nowhere else; and the majority of them, like most of Madagascar’s mammals, are nocturnal (Martin, 1972a). Lemurs are the best-known animals of Madagascar’s wildlife, attracting worldwide scientific and ecotourist attention to the island’s unique biodiversity. Lemurs are used as indicators of ecological monitoring, and their presence has been an important factor behind the creation of numerous protected areas on the island (Durbin, 1999). The distinctiveness of Madagascar’s flora and fauna, particularly the lemurs, was one of the deciding factors that attracted me to do my doctoral research there. Many other researchers have been similarly captivated, and the wealth of recent research on the island has been excellently compiled and summarized in an ambitious reference tome, The Natural History of Madagascar (Goodman and Benstead, 2003).

In Madagascar, I became part of a cohort of scientists eager to understand the lives of nocturnal primates. My study is now one of many that paint a broad picture of previously unsuspected variety and complexity within the world of nocturnal primates. Many colleagues old and new continue to make important contributions to nocturnal primate ecology and social behavior. In this monograph, I pay tribute to their continued efforts while presenting my own research on the brown mouse lemur Microcebus rufus, in Ranomafana National Park (RNP), a block of lush rainforest in the southeastern part of the island. During the seventeen months of my field study, I collected data on many aspects of the brown mouse lemur’s biology. Some aspects were studied more comprehensively than others, but in total the research focused on establishing the important events that mark the annual life cycle of mouse lemurs at RNP. In this chapter, I present some initial background information on mouse lemurs and the family to which they belong, the Cheirogaleidae. Some of these varied topics will be developed further in chapters to follow. My hope is that the readers of this volume will find mouse lemurs as exciting as I did when I first stepped into the rainforest of Ranomafana’s national park.

THE CHEIROGALEIDAE

Mouse lemurs are strepsirrhines—that is, they belong to the suborder of primates called the Strepsirrhini, which also includes the other Malagasy lemurs, the galagos (bushbabies) of sub-Saharan Africa, and the lorises of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. The Strepsirrhini are characterized by the development of a tooth comb in which the anterior lower teeth are elongated, slender, and procumbent (Rasmussen and Nekaris, 1998). [An exception to this feature is the aye-aye, Daubentonia madagascariensis, which may have lost the trait as its teeth specialized in a different way (Ankel-Simons, 1996).] Extant strepsirrhine primates also possess a grooming claw instead of a nail on the second pedal digit (Schwartz and Tattersall, 1985).

Primates in the suborder Strepsirrhini are characterized by a moist, naked rhinarium similar to the wet noses of cats and dogs—in that sense, there exist both primate and nonprimate strepsirrhine mammals. In contrast, members of the other primate suborder, the Haplorhini (monkeys, apes, and humans) possess a dry, hairy upper lip. [Prosimian is another taxonomic grouping used to designate lemurs, lorises, galagos, as well as tarsiers and all early primates (Fleagle, 1998), but in this volume I mostly use Strepsirrhini, and Haplorhini, to refer to the principal primate taxa.] The strepsirrhine rhinarium is linked through the split upper lip to a membrane of the oral cavity, the vomeronasal or Jacobson’s organ, where airborne odor molecules such as pheromones are processed (Rouquier et al., 2000; Liman and Innan, 2003). Primate strepsirrhines share this trait, indicative of a well-developed olfactory system, with many nonprimate mammals (carnivores, insectivores, rodents, bats, and more).

Yet another trait shared by strepsirrhine mammals is the tapetum lucidum. Located behind the retina of many diurnal and nocturnal strepsirrhines, the tapetum lucidum is a reflecting membranous layer that enhances the eye’s ability to register light by increasing retinal sensitivity in low-light conditions (Pariente, 1979; Martin, 1994). The tapetum lucidum has played a prominent role in discussions regarding ancestral primate adaptations. Accepted wisdom viewed the membrane as an adaptation specifically for the nocturnal lifestyle, and because it is found in diurnal strepsirrhine primates as well as nocturnal ones, it was held that all strepsirrhines were descendent from a nocturnal ancestor (Martin, 1994). Recent evidence has cast doubt on this scenario. Tan et al. (2005) discovered, through comparative genetic analysis of opsin genes (involved with color vision), that ancestral primates may have been cathemeral or even diurnal. The researchers proposed that different groups of primates shifted to nocturnal activity at different times in evolutionary history and as they did so, nocturnal features were strengthened whereas diurnal ones were lost or relaxed. Today, the presence of the tapetum lucidum in nocturnal primates is a lucky perk for the researcher as the membrane reflects brightly when subjects are observed by flashlight. The yellow-orange glow is considerably helpful in locating animals in the dark and can be especially useful, as I discovered, when observing animals in thick forest.

Among the strepsirrhines, mouse lemurs, genus Microcebus, belong to the family Cheirogaleidae, a group of small-bodied (<500 g), arboreal, primarily quadrupedally locomoting, nocturnal lemurs that includes: Cheirogaleus (dwarf lemurs), Mirza (giant mouse lemurs), Phaner (fork-crowned lemurs), and the monotypic Allocebus trichotis (hairy-eared dwarf lemur), the latter long thought to be extinct but rediscovered (Meier and Albignac, 1991; Groves, 2005). Among the Cheirogaleidae, chromosomal studies show that there are cytogenetic differences between Phaner and the other species (Rumpler et al., 1994), whereas molecular research indicates that Allocebus, Mirza, and Microcebus are more closely related to each other than to Cheirogaleus (i.e., they form a clade or monophyletic group of species) (Pastorini et al., 2001). Lastly, Mirza and Microcebus may be more closely related to each other than to the other members of the family (Rumpler et al., 1994).

Cheirogaleids display features that are relatively unusual among primates but are common among other small mammals. Species of Cheirogaleus and Microcebus and possibly Allocebus trichotis are the only primates known to enter periods of hypothermia and lethargy, either daily or seasonal, the latter after accumulating body fat. As will be discussed in later chapters, these behaviors represent adaptations for coping with stressful environmental conditions. Another unusual, for primates, feature is that cheirogaleids commonly produce litters that consist of two to four offspring.

Patience and persistence, mandatory requirements for the nocturnal primate researcher, have yielded a plethora of information on diet, life history, and reproduction although the most exciting discoveries concern cheirogaleid sociality. Members of the family were generally thought to be nongregarious, usually foraging alone at night and not found active within cohesive social groups. We are aware now that cheirogaleids do not lack a social life and that they typically form well-defined but dispersed social networks of rich diversity. Even their daytime sleeping associations constitute an important element of their social life.

Cheirogaleus medius, the lesser dwarf lemur, a species that among primates has the unique ability to hibernate annually for seven months (Dausmann et al., 2004), has been found to form permanent pair bonds while at the same time engaging in extra pair couplings during the reproductive period (Müller 1998, 1999a,b,c; Fietz, 1999a,b; Fietz et al., 2000; see Fietz, 2003a for a review). Mirza coquereli, Coquerel’s mouse lemur, at Kirindy Forest (a site near Morondava on the west coast, where research on several cheirogaleids is ongoing) lives in matrilinear clusters in which members actively defend borders (Kappeler, 1997a, 2003; Kappeler et al., 2002). Phaner furcifer, the Masoala fork-crowned lemur, an exudate specialist, spends the majority of the night alone but maintains vocal contact with its mate. The pair engages in conflicts with other pairs over access to exudate trees (Schülke, 2003). Little information on Allocebus trichotis exists, but even for this species, it is known that several individuals sleep together in tree holes (Rakotoarison et al., 1997).

Mouse lemurs are found throughout Madagascar although to date much of the research has taken place in the dry, deciduous forests of Madagascar’s west coast. Madagascar is in the southern hemisphere and the seasons are inverse. Thus, the problem that confronts lemurs in dry forests, is survival during the dry season, or the austral winter, when food resources are scarce. Over thirty years ago, seminal field research primarily on the grey mouse lemur, Microcebus murinus, laid the foundations for understanding mouse lemur natural history, establishing this species as an omnivore, with seasonal shifts in diet, activity levels, body weight, and body temperature (Martin, 1972b, 1973; Pagès, 1978, 1980; Charles-Dominique and Petter, 1980; Hladik et al., 1980; Barre et al., 1988; Pagès-Feuillade, 1988). Seasonal behaviors were also observed in captivity (e.g., Petter-Rousseaux, 1974, 1980; Petter-Rousseaux and Hladik, 1980; Aujard et al., 1998; Génin and Perret, 2000) and found to be linked to changes in photoperiod affecting the pituitary gland (Petter-Rousseaux, 1970, 1974, 1980; Martin, 1972c; Perret, 1972; Perret and Aujard, 2001). Other cheirogaleids of dry forests were found to maintain dietary specializations, seasonal patterns in food intake, body fat accumulation, and the ability to enter daily or seasonal periods of lethargy. These were considered to be adaptations to the highly seasonal conditions of food availability in the forests of the west coast (Petter-Rousseaux, 1980; Petter-Rousseaux and Hladik, 1980; Schmid, 1996; Fietz, 2003b; Kappeler, 2003). The diet of the grey mouse lemur typified omnivory, encompassing fruit, insects, flowers, buds, gums, nectars, plant and insect secretions, small vertebrates, and some leaves (Martin, 1972b, 1973; Hladik et al., 1980; Barre et al., 1988; Corbin and Schmid, 1995; Génin, 2001).

The ability to enter a hypothermic state is a particularly fascinating aspect of mouse lemur biology. This phenomenon is commonly associated with species that live in northern climates, including many rodents such as chipmunks (Tamias), ground squirrels (Spermophilus), prairie dogs (Cynomys), marmots (Marmota), and hamsters (Cricetus) (French, 1988). Bats also undergo daily and seasonal periods of hypothermia (e.g., Altringham, 1996). Like bats, mouse lemurs experience daily torpor and seasonal prolonged hibernation (Ortmann et al., 1996, 1997; Schmid et al., 2000). Research at Kirindy on the physiology of torpor has revealed that, during the wet season, mouse lemurs accumulated body fat that was metabolized during t...