- 546 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Making of the American Landscape

About this book

The only compact yet comprehensive survey of environmental and cultural forces that have shaped the visual character and geographical diversity of the settled American landscape. The book examines the large-scale historical influences that have molded the varied human adaptation of the continent's physical topography to its needs over more than 500 years. It presents a synoptic view of myriad historical processes working together or in conflict, and illustrates them through their survival in or disappearance from the everyday landscapes of today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Making of the American Landscape by Michael P. Conzen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralChapter one

Recognizing Nature's bequest

NORTH AMERICA is a large continent, spanning fully 115 degrees of longitude and about 75 degrees of latitude. That size is sometimes difficult for Europeans to quite comprehend. The story is told, no doubt apocryphal, that the outcome of the Second World War was manifest to German prisoners of war only after five days of continuous rail travel had failed to deliver them from the east coast to the west coast.

The continent is also one of contrasts. It spans tropics to tundra, searing heat to bitter cold, mild marine conditions to severe continental effects, continual wetness to permanent desiccation, mountains to almost featureless plains, absence of plant life to vegetative abundance. Perhaps, also, North America has had its physical environment transformed more rapidly at the hands of people than any other large part of the world. Generally within less than 200 years, near-primeval land has sprouted farms and cities, forests have been removed or changed, and severe hydrologic and geomorphic disruptions have sometimes ensued.

No understanding of these profound transformations can be gained without first considering the nature of the stage upon which the human drama has unfolded. This opening chapter sketches an outline portrait of the physical environment of mid-latitude North America. The continent's size, internal contrasts, and complexity can only be hinted at, and the reader is encouraged to read further, particularly with the aid of a good atlas that will complement the few illustrations that can be offered here.1 This portrait lays out the composition of the continent's natural regions through the broad brushstrokes of climate, landform, vegetation, and soil.

Climates

Since the dawn of time on this planet, life at the surface has been conditioned by the continuous interaction of the earth's internal forces with the enveloping atmosphere. Dynamic and historically volatile, this interaction has produced periods of apparent equilibrium in which, from the perspective of human experience, characteristic patterns of climate seem to emerge.

Many things conspire to give North America the climate it has, as one should expect for a continent so large and diverse. The first of these is the continent's very mid-latitude location. This means that the noon sun angle is low in winter, ensuring receipt of limited solar energy at that time. Also, the latitude places much of the continent in the path of the Westerlies wind belt and thus in the paths of mid-latitude cyclones or “storm-tracks.” These cyclones, together with air masses, control the genesis of much of the weather over the continent.

A second climatic circumstance is the presence of source regions for varied air masses which converge upon and interact in the traveling cyclones. Because these air masses tend not to mix, their common boundaries mark the cold and warm fronts of the mid-latitude cyclones. Four air masses affect America. There is maritime tropical air, which is warm and moist and originates in the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, but also comes from the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California and Mexico. Maritime polar air, cool and moist, comes primarily from the North Pacific, and also from the North Atlantic. Continental polar air masses, which are cool to cold and dry, form in central to northern Canada and move south to southeasterly across the continent. Continental tropical air masses round out the symmetrical quartet, and these are warm and dry, forming over the desert of north Mexico.

The very size of the continent, itself, also conditions climate by creating a “continental” effect. Temperatures over central Canada can range from over 100°(F) in summer to perhaps −50° or below in winter. At the same time, the atmosphere over the ocean on either side has a much smaller range. The continental effect also creates a monsoon, or seasonal wind, although not nearly as strong as that found in Southeast Asia. The cold winter air of the continental interior, being denser, produces a thermally induced high-pressure zone so that the general flow of air, in conjunction with the upper Westerlies, is to the south and east. No topographic barriers exist in the mid-continent, so the polar continental air can often move to the Gulf of Mexico. Texans often joke that the only barrier between them and the Arctic Ocean is a barbed-wire fence. Summer finds a reversal of flow with tropical maritime air drawn from the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic into the continental interior.

Ocean currents provide another control. The cold California Current flows southward along the west coast and can have an effect some distance inland. The warm Gulf Stream flows northward along the southeast coast as far north as North Carolina. Meanwhile, the cold Labrador Current flows southward along the northeast coast, sometimes slipping in between the coast and the Gulf Stream as far south as Virginia and chilling local weather.

Another climatic influence is the wind and pressure system. The Westerlies carry with them the endless stream of mid-latitude cyclones that attract the air masses, and create much of the weather for the continent. At the surface, these Westerlies bring the marine atmospheric conditions of the Pacific Ocean onto the coast from Alaska to Oregon, and seasonally (in winter) to California. Meanwhile, there is a large subtropical high-pressure cell that has a semi-permanent position over the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Mexico; this keeps much of northwestern Mexico dry and seasonally (in summer) keeps California dry. Because there are no prevailing winds blowing onto the east coast, maritime influences are usually restricted to the coastline. Severe continental conditions of heat and cold thus prevail across the interior almost to the east coast. The inland suburbs of Boston, for example, record extreme winter temperatures almost as cold as those at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, at the same latitude but far inland.

Some low-pressure systems affecting the continent are destructive. Tropical cyclones, or hurricanes, form over the South Atlantic or Gulf of Mexico in late summer and autumn and move most often into the Gulf or northward along the east coast. The destruction along the coast from their wind, tides, and rain is well known, but once they move inland, they are less destructive and bring heavy rains, often breaking the late-summer droughts that sometimes grip the Southeast. Thus, their constructive effects offset the destructive ones to some degree. Such hurricanes also form in the Pacific and affect the Southwest, but are less common. Tornadoes are destructive cyclones caused by severe atmospheric instability (high moisture and environmental lapse rates) and occur in the eastern half of the continent during the warm season. Oklahoma and Kansas are the tornado kingdoms of America, as one will recall from the Wizard of Oz.

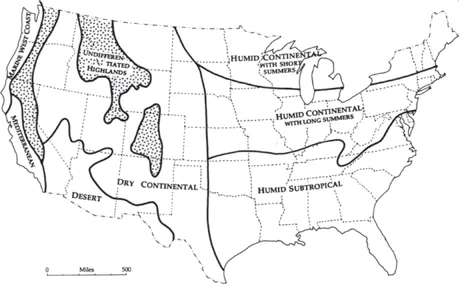

Mountains strongly affect climate. The chain of high mountains extending the entire length of the west coast effectively blocks most moisture from penetrating into the continental interior. Thus, the windward (western) sides of these mountains are wet while the leeward (eastern) sides are dry. Coastal mountains in Oregon get as much as 100 inches of rain annually while eastern Oregon gets as little as one-tenth of that. This process leaves the central part of the continent with little moisture; the only other source of moisture is occasional maritime tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico. Because the distances are so great and the prevailing winds blow eastward, not much of this air reaches the mid-continent, so it is relatively dry. Further east there is a greater probability of getting such air and so there is more annual rainfall. With these genetic processes in mind, it is now possible to understand the characteristics and distribution of climates (Fig. 1.1).

The humid subtropical climate is controlled by maritime tropical air during the summer and an alternation of that with polar continental air in winter, when mid-latitude cyclones are common. Summers are hot and humid, much like the wet tropics, while the winter weather alternates between cool and warm spells with frequent cyclonic rain. Very cold temperatures are then possible. Americans from the North tend to perceive Alabama, for example, as “tropical,” but Alabama has experienced temperatures as low as −20°. Precipitation may be heavy in individual storms and the area averages 40–80 inches per year.

Figure 1.1

Major climatic regions in the United States.

Major climatic regions in the United States.

The humid continental climate with a long summer is a cooler version of the first climate. The winter is longer, the coldest month will average below 32°, and more snows and colder extremes are possible. Snowfall usually totals on the order of 20–40 inches. St. Louis, for example, has a January average temperature of 20°, but extremes of −22° are possible. The summers have more cyclonic (frontal) activity and have slightly cooler average temperatures, but the temperature and humid extremes will be as high as in the humid subtropical climate further south. At least one geographer has called this zone “the misery belt,” and notes that this is the perfect climate for growing corn—long summer days at mid-high latitudes, plenty of rain, warm temperatures—“but for anyone whose aesthetic requirements transcend those of a cornstalk, the climate is pretty darned miserable, winter or summer.”2

The humid continental climate with a short summer has cyclonic rainfall all year, but summer brings some great convectional thunderstorms. Although the summer temperature may be cool, that results from the averaging of some very cool days when polar continental air dominates, and some very hot and humid days (perhaps over 100°) when tropical maritime air dominates. Mercifully, this is not too common. Winter, on the other hand, is brutal and long. Temperatures may go below −50°, snow may be on the ground for several months, and spring may not arrive until May, with hot temperatures often coming in June. Rain may average 20–40 inches and there is a decided maximum during the long days of summer.

In the dry continental climate, mountains curtail moisture from the west while the prevailing upper Westerlies and the great distances from the Gulf limit the supply of tropical maritime air. Annual average rainfall ranges from about 10 inches in the west to about 20 inches in the east. There are great seasonal temperature contrasts. Winter temperatures to the north are more severe where there are frequent incursions of polar continental air, while the summers there are shorter and milder. Snow is possible over much of the region and may remain a month or more.

The desert, located in the Southwest, is cut off from moisture on all sides. It is also influenced by the Pacific subtropical high-pressure cell. The net result is a large region receiving on average less than 10 inches annual precipitation. Although summer temperatures may reach 115° or more, the winters can be quite cool and snow is possible.

The so-called Mediterranean climate is also known as dry-summer subtropical. The summer dry season is controlled by the northward shift of the Pacific high-pressure cell whereas the winters see a southward shifting of the Westerlies with their mid-latitude cyclones and fronts, all producing winter rainfall. Cold temperatures and frost are uncommon in winter, while the summers are hot inland but greatly m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Titles of related interest

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgements

- Table of Contents

- Foreword to the First Edition

- Introduction

- 1 Recognizing Nature's bequest

- 2 Retrieving American Indian landscapes

- 3 Refashioning Hispanic landscapes

- 4 Retracing French landscapes in North America

- 5 Americanizing English landscape habits

- 6 Transforming the Southern plantation

- 7 Gridding a national landscape

- 8 Clearing the forests

- 9 Remaking the prairies

- 10 Watering the deserts

- 11 Inscribing ethnicity on the land

- 12 Organizing religious landscapes

- 13 Mechanizing the American earth

- 14 Building American cityscapes

- 15 Asserting central authority

- 16 Creating landscapes of civil society

- 17 Imposing landscapes of private power and wealth

- 18 Paving America for the automobile

- 19 Developing large-scale consumer landscapes

- 20 Designing the American utopia: Refections

- Contributors

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index