- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Interpreting Our Heritage

About this book

Every year millions of Americans visit national parks and monuments, state and municipal parks, battlefields, historic houses, and museums. By means of guided walks and talks, tours, exhibits, and signs, visitors experience these areas through a very special kind of communication technique known as “interpretation.” For fifty years, Freeman Tilden’s Interpreting Our Heritage has been an indispensable sourcebook for those who are responsible for developing and delivering interpretive programs. This expanded and revised anniversary edition includes not only Tilden’s classic work but also an entirely new selection of accompanying photographs, five additional essays by Tilden on the art and craft of interpretation, a new foreword by former National Park Service director Russell Dickenson, and an introduction by R. Bruce Craig that puts Tilden’s writings into perspective for present and future generations.

Whether the challenge is to make a prehistoric site come to life; to explain the geological basis behind a particular rock formation; to touch the hearts and minds of visitors to battlefields, historic homes, and sites; or to teach a child about the wonders of the natural world, Tilden’s book, with its explanation of the famed “six principles” of interpretation, provides a guiding hand.

For anyone interested in our natural and historic heritage — park volunteers and rangers, museum docents and educators, new and seasoned professional heritage interpreters, and those lovingly characterized by Tilden as “happy amateurs” — Interpreting Our Heritage and Tilden’s later interpretive writings, included in this edition, collectively provide the essential foundation for bringing into focus the truths that lie beyond what the eye sees.

Whether the challenge is to make a prehistoric site come to life; to explain the geological basis behind a particular rock formation; to touch the hearts and minds of visitors to battlefields, historic homes, and sites; or to teach a child about the wonders of the natural world, Tilden’s book, with its explanation of the famed “six principles” of interpretation, provides a guiding hand.

For anyone interested in our natural and historic heritage — park volunteers and rangers, museum docents and educators, new and seasoned professional heritage interpreters, and those lovingly characterized by Tilden as “happy amateurs” — Interpreting Our Heritage and Tilden’s later interpretive writings, included in this edition, collectively provide the essential foundation for bringing into focus the truths that lie beyond what the eye sees.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

I have been careful to retain as much idiom as I could, often at the peril of being called ordinary and vulgar. Nations in a state of decay lose their idiom, which loss is always precursory to that of freedom.… Every good writer has much idiom; it is the life and spirit of language: and none such ever entertained a fear or apprehension that strength and sublimity were to be lowered and weakened by it.… Speaking to the people, I use the people’s phraseology.

— Demosthenes to Eubulides, in Imaginary Conversations, by Walter Savage Landor

Chapter 1: Principles of Interpretation

The word “interpretation” as used in this book refers to a public service that has so recently come into our cultural world that a resort to the dictionary for a competent definition is fruitless. Besides a few obsolete meanings, the word has several special implications still in common use: the translation from one language into another by a qualified linguist; the construction placed upon a legal document; even the mystical explanation of dreams and omens.

Yet every year millions of Americans visit the national parks and monuments, the state and municipal parks, battlefield areas, historic houses publicly or privately owned, museums great and small—the components of a vast preservation of shrines and treasures in which may be seen and enjoyed the story of our natural and man-made heritage.

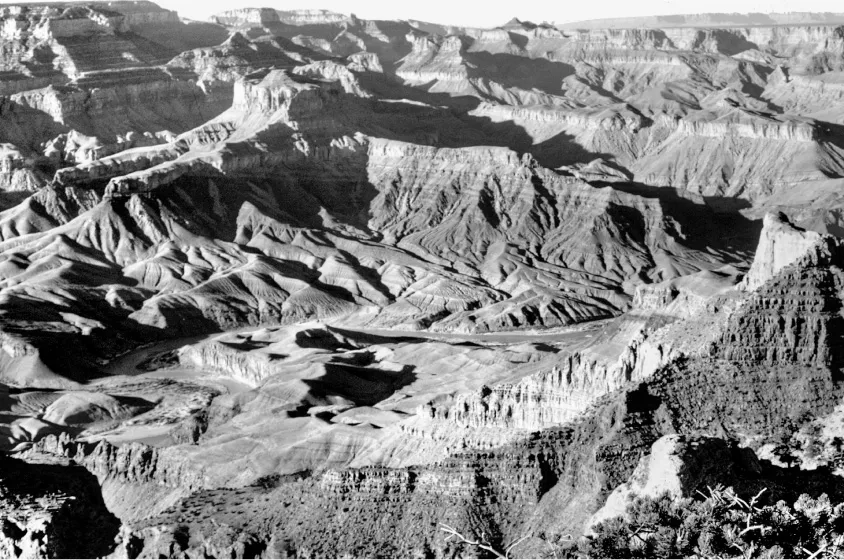

In most of such places the visitor is exposed, if he chooses, to a kind of elective education that is superior in some respects to that of the classroom, for here he meets the Thing Itself—whether it be a wonder of nature’s work, or the act or work of man. “To pay a personal visit to a historic shrine is to receive a concept such as no book can supply,” someone has said; and surely to stand at the rim of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado is to experience a spiritual elevation that could come from no human description of the colossal chasm.

Thousands of naturalists, historians, archaeologists, and other specialists are engaged in the work of revealing, to such visitors as desire the service, something of the beauty and wonder, the inspiration and spiritual meaning that lie behind what the visitor can with his senses perceive. This function of the custodians of our treasures is called interpretation.

Because of the fear of misconception arising from conflicting definitions of the word, and also because some have thought it a pretentious way of describing what they believe to be a simple activity, there has been objection to the use of the word “interpretation” even among those engaged in this newer device of education. For myself I merely say that I do not share this objection. I have never been able to find a word more aptly descriptive of what we middlemen, either in the National Park Service or in any institution employing the means, are attempting to do.

But all during the practice of this educational activity, whether science or art or something of both, there has existed a strange situation. Interpretation has been performed—excellent, good, fair, and unsatisfactory—with only a vague reference to any philosophy upon which interpretation could be based.

I have heard some superb interpretations not only in the National Park Service areas, but in far lesser places, and have found by interrogation that the interpreter was aware of no principles, but was merely following his inspiration. I actually believe that if there were enough pure inspiration in the world to go around, this might be the best way to perform the service. But we are not so cluttered with genius as all that. You have only to attend some of the worse performances in interpretation to wish heartily that there were some teachable principles, and perhaps some schools for interpreters.

This book results from a study of interpretation as practiced in the many and diverse cultural preserves I have mentioned and from an inquiry as to whether there is such a philosophy, whether there are such basic principles, upon which the interpreter may proceed with an assurance that, though he may not be inspired, he will do an adequate job.

Since the earliest cultural activities of man there have been interpreters. Every great teacher has been an interpreter. The point is that he has seldom recognized himself specifically as such, and his interpretation has been personal and implicit as a part of his instruction. In a sermon called “A Christmas Message,” Harry Emerson Fosdick showed what seems to me a profound knowledge of the highest meaning of this word, in speaking of Jesus. He said: “There are two kinds of greatness. One lies in the genius of the gigantic individual who … shapes the course of history. The other has its basis in the genius of the revealer—the man or woman who uncovers something universal in the world that has always been here and that men have not known. This person’s greatness is not so much in himself as in what he unveils.… [T]o reveal the universal is the highest kind of greatness in any realm.”

The reason why our college graduates, in past decades, have spoken with such reverence and affection of certain of their teachers—such men as Copeland and Charles Eliot Norton of Harvard and Bumpus of Brown, to name just three among many—was because such men by universality of mind instinctively went behind the body of information to project the soul of things. One of his pupils said of Dr. Bumpus: “He thoroughly enjoyed his stay upon this planet, which he found so full of a number of things … and he enjoyed pointing out these things in a new light.… He never forgot that the feeling of an exhibit and the need for it to tell a story were quite as important as its factual truthfulness.”

To take a slice of a tree like the giant sequoia, and to associate its growth rings with a time chart of our human history, was an idea that occurred to some master interpreter.

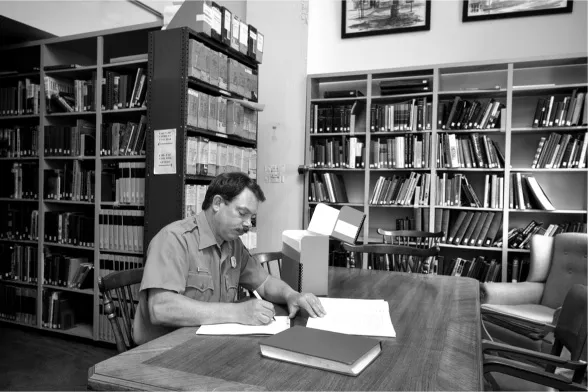

Since interpretation is a growth whose effectiveness depends upon a regular nourishment by well-directed and discriminating research, this introductory chapter seems as good a place as any to stress the importance of that resource. In an article printed in the magazine Antiques, Edward P. Alexander of Colonial Williamsburg, speaking of historic preserves, wrote: “Research is a continuing need and the life blood of good preservations. Both historical authenticity and proper interpretation demand facts. Research is the way to obtain these facts. There is no substitute for it, and no historic preservation should be attempted without research.”

Colonial Williamsburg itself offers an ideal example of this truth. Here it is possible, through the generosity of Mr. Rockefeller, to employ the skill and taste of the most competent researchers in many fields to the end of bringing to life accurately and beautifully a segment of our early American history.

In the National Park Service is found an abundance of proof of the statement, and not merely in the department of history. Research is responsible for the satisfactory and stimulating experience of the visitor to Crater Lake, where the interpretation takes the visitor beyond the point of his aesthetic joy toward a realization of the natural forces that have joined to produce the beauty around him. This experience is made possible through continuing research here, because the explanation first accepted of the origin of the mighty caldera was not that which is now generally held. Nor was the research at Crater Lake alone that of the geologist. Many other specialists, including the archaeologist, had their part in revealing the facts.

Visiting a historic shrine is a unique, sometimes life-changing experience. (Courtesy of National Park Service)

To stand at the rim of the Grand Canyon is to experience a spiritual elevation that could come from no human description of that colossal chasm. (Courtesy of National Park Service)

The vivifying programs at the Custis-Lee Mansion in Arlington, Virginia, emerge from the painstaking efforts of the historian who was not content with large generalizations but sought in the records of the two families a multitude of homely details that bring the Custises and Lees into touch with our own daily experience.

At Fort Necessity, associated with the young George Washington, “something was wrong with the picture,” as we say, yet cursory observation and guess had failed to arrive at the facts. Indeed a palisade reconstruction had been based upon false premises. A park service archaeologist who refused to give up, even though many times baffled, was finally able to depict this tiny frontier post as it really was.

It had been commonly said for many years that the Nelson bighorn sheep had entirely disappeared from the confines of Death Valley National Monument. Indeed, so it was believed by practically all except the sheep themselves, whose rather important numbers now are made a matter of fact through the efforts of a naturalist, Ralph Wells, who has “lived” with flocks of the animals in the furnace-hot summer of the valley.

Dinosaur National Monument comes to mind readily in this regard; so, naturally, does Jamestown, where digging in preparation for the Exposition of 1957 made it finally possible to people that little first settlement of the English-speaking colonists and gave the ancient inhabitants flesh on their bones and blood in their veins.

When I consider what competent research can do in a yawning void, my mind goes to Fort Frederica, in Georgia, for it is natural for us to draw upon impressions that are gained at first hand. Previous to the work of the archaeologist, teamed with the historian, at Oglethorpe’s colony on the sea-island near Brunswick, I attempted some volunteer interpretation there at a time when there was not sufficient personnel present to aid the visitors. Charming as was that ancient ruin, with its live oaks and soothing estuary frontage, I found it almost impossible to make it real. I knew the historical background well enough, but the eyes of the visitors constantly wandered from me. I knew what they were thinking: “What was it like?” The structural relics were not imposing. The mounds might be those of earthwalls, but they did not register.

Well, I went to Frederica again, after the diggers had uncovered the site of the Hawkins-Davison houses, and again I had the pleasure of telling the story of Frederica to certain groups. What a difference those bricks and those exposed walls made! Somebody had lived here; this was part of a town, it now had a being.

Careful research is the foundation of the interpreter’s art. (Photo by Dan Riss)

Ruins like these at Chaco Culture National Historic Park often serve as the catalyst for visitors to glimpse the past. Here, as in every interpretive activity, the chief aim of interpretation is not instruction but provocation. (Courtesy of National Park Service)

Some years ago, in scrambling up a steep hillside of the Jemez Mountains of New Mexico, I found the ground well strewn with petrified marine shells of several species. I was at an elevation of not less than 7,000 feet. The discovery did not surprise me in the least; but it did make me wonder what the prehistoric Americans who must have seen such shells had thought about them. I knew that I was standing somewhere near the shoreline of a shallow sea that occupied this spot at a time before the land had been slowly upraised. How did I know this? The story had been interpreted for me; seemingly unrelated facts had been reasoned into a whole picture that solved all difficulties.

For dictionary purposes, to fill a hiatus that urgently needs to be remedied, I am prepared to define the function called interpretation by the National Park Service, by state and municipal parks, by museums and similar cultural institutions as follows:

An educational activity which aims to reveal meanings and relationships through the use of original objects, by firsthand experience, and by illustrative media, rather than simply to communicate factual information.

This, let me emphasize, is for the dictionary, which logically attempts only an objective definition of words as they are, or have been, commonly accepted. The true interpreter will not rest at any dictionary definition. Besides being ready in his information and studious in his use of research, he goes beyond the apparent to the real, beyond a part to a whole, beyond a truth to a more important truth.

So, for the consideration of the interpreter, I offer two brief concepts of interpretation, one for his private contemplation, and the other for his contact with the public. First, for himself: interpretation is the revelation of a larger truth that lies behind any statement of fact.

The other is more correctly described as an admonition, perhaps: interpretation should capitalize mere curiosity for the enrichment of the human mind and spirit.

In the matter of definition, I have tried to arrive at something upon which we can fairly well agree. We are seldom entirely happy with the utmost pains of the lexicographer: we find words given as synonymous that we do not so consider; a definition is too inclusive, or it fails to emphasize that which we believe is vital. As to the concepts given above, I should hope that the interpreter will have others of his own, doubtless just as valid and just as stimulating. If we can agree upon principles, the stress and shading of the individual will be no impairment but a reflection of his true appreciation of those principles.

Now, what are these principles? I find six bases that seem enough to support our structure. There is no magic in the number six. It may be that my reader will point out that some of these principles interfinger. It may be that he will feel that, after all, there is but one, and all the others are corollary. On the other hand, since I am ploughing a virgin field so far as a published philosophy of the subject is concerned, some of my readers may be provoked into adding further furrows. Very well. This book pretends to no finality, no limitation. We are clearly engaged in a new kind of group education based upon a systematic kind of preservation and use of national cultural resources. The scope of this activity has no counterpart in older nations or other times.

I believe that interpretive effort, whether written or oral or projected by means of mechanical devices, if based upon these six principles, will be correctly directed. There will inevitably be differences in excellence arising from varied techniques and from the personality of the interpreter. Obviously I cannot be concerned with those factors in such a book as this. The National Park Service has an extensive manual and a number of admirable booklets for the governance of the spot-conduct of both the interpreter and his interpretation.

Here, then, are the six principles:

1. Any interpretation that does not somehow relate what is being displayed or described to something within the personality or experience of the visitor will be sterile.

2. Information, as such, is not interpretation. Interpretation is revelation based upon information. But they are entirely different things. However, all interpretation includes information.

3. Interpretation is an art, which combines many arts, whether the materials presented are scientific, historical, or architectural. Any art is in some degree teachable.

4. The chief aim of interpretation is not instruction, but provocation.

5. Interpretation should aim to present a whole rather than a part and must address itself to the whole man rather than any phase.

6. Interpretation addressed to children (say, up to the age of twelve) should not be a dilution of the presentations to adults but should follow a fundamentally different approach. To be at its best it will require a separate program.

I plan to make no generalizations in this book without the support of one or more illustrations or examples. My aim is clarity and succinctness, rather than style, even though I recommend that the interpreter never forget that “style” is a priceless ingredient of interpretations. “What is style?” somebody asked of a French writer. “Le style, c’est l’homme,” was the reply. (Style is just the man himself.) So style is just the interpreter himself. How does he give it forth? It emerges from love. We shall later have a little chapter upon love. I do not name it here as a principle. It is, indeed, not a principle but a passion.

Chapter 2: The Visitor’s First Interest

As we read, we must become Greeks, Romans, Turks, priest, king, martyr and executioner; must fasten these images to some reality in our secret experiences.—Ralph Waldo Emerson

...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Interpreting Our Heritage

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction to the Fourth Edition

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Interpreting Our Heritage by Freeman Tilden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.