eBook - ePub

The Wages of History

Emotional Labor on Public History's Front Lines

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Anyone who has encountered costumed workers at a living history museum may well have wondered what their jobs are like, churning butter or firing muskets while dressed in period clothing. In The Wages of History, Amy Tyson enters the world of the public history interpreters at Minnesota's Historic Fort Snelling to investigate how they understand their roles and experience their daily work. Drawing on archival research, personal interviews, and participant observation, she reframes the current discourse on history museums by analyzing interpreters as laborers within the larger service and knowledge economies.

Although many who are drawn to such work initially see it as a privilege—an opportunity to connect with the public in meaningful ways through the medium of history—the realities of the job almost inevitably alter that view. Not only do interpreters make considerable sacrifices, both emotional and financial, in order to pursue their work, but their sense of special status can lead them to avoid confronting troubling conditions on the job, at times fueling tensions in the workplace.

This case study also offers insights—many drawn from the author's seven years of working as an interpreter at Fort Snelling—into the way gendered roles and behaviors from the past play out among the workers, the importance of creative autonomy to historical interpreters, and the ways those on public history's front lines both resist and embrace the site's more difficult and painful histories relating to slavery and American Indian genocide.

Although many who are drawn to such work initially see it as a privilege—an opportunity to connect with the public in meaningful ways through the medium of history—the realities of the job almost inevitably alter that view. Not only do interpreters make considerable sacrifices, both emotional and financial, in order to pursue their work, but their sense of special status can lead them to avoid confronting troubling conditions on the job, at times fueling tensions in the workplace.

This case study also offers insights—many drawn from the author's seven years of working as an interpreter at Fort Snelling—into the way gendered roles and behaviors from the past play out among the workers, the importance of creative autonomy to historical interpreters, and the ways those on public history's front lines both resist and embrace the site's more difficult and painful histories relating to slavery and American Indian genocide.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wages of History by Amy Tyson,Amy M. Tyson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Massachusetts PressYear

2015Print ISBN

9781625340245, 9781625340238eBook ISBN

9781613763230PART I

Public History’s Emotional Proletariat (1960–1996)

CHAPTER 1

PERFORMING A PUBLIC SERVICE

From Historic Site to Work Site (1960–1985)

On a spring Sunday in 1965, Mr. Richard J. Weiss—a lifelong resident of Minnesota—visited Fort Snelling to fly kites with his children. While there, he and his family toured the old Fort’s buildings and visited the newly opened Fort Snelling State Park, which lay at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. Dismayed by what he saw, Weiss wrote a concerned letter to the Minnesota Department of Conservation noting that he had “never seen a historical place in such poor shape.”1

Weiss described his visit to the state park as a disappointing “long walk through uninteresting bottom lands” that ended “at a despicable dump,” and he found his tour of the old Fort—a National Historic Landmark since 1960—similarly wanting. In 1965, of the Fort’s four original buildings only one was being actively renovated, while two of the buildings—Weiss was dismayed to discover—were “inhabited by doctors and VA [Veterans Administration] personnel free loading [sic] in these historical places for a pitance [sic]” paid in rent. Ultimately, Weiss wanted to see more evidence of planning at the historic site and park; specifically, he wanted the dump buried, the VA evicted, and the buildings and furnishings of the original Fort restored and reconstructed. Little could Weiss have predicted that by 1970 the Fort would have several restored buildings and a fledgling workforce of living history interpreters who were hired to interact with tourists and perform work displays appropriate to the 1820s.

Focusing on the period from 1960 to 1985, this chapter examines archival materials related to Historic Fort Snelling’s early interpretive programming, qualitative data, and training materials developed for the site’s growing cadre of living history interpreters, all of which draw attention to the relationship between the production of public history and the performance of customer service. The chapter provides a window into several areas of tension that significantly affected the experience of living history for both workers and consumers.

One of those areas of tension lay in the gendered work displays at the living history museum. While the labor of male and female interpreters attempted to represent the historical divide between male and female labor at the post in the 1820s, not only were some of those purportedly historical performances misleading, they also led to differing expectations for male and female interpreters with regard to the emotional work displays required of them. And in the male workforce, internal tensions arose as the military chain of command enacted was used for social control of the Fort’s contemporary workforce (so that, for instance, male interpreters playing the roles of soldiers with the rank of private on the bottom of that chain were expected to follow orders from co-workers assigned to play their superiors).

While some workers may have taken pleasure in this slippage between past and present, examining the archival evidence alongside qualitative data reveals an interpretive workforce divided between those who took pleasure in the job primarily because it provided opportunities for “playing soldier,” and those who valued it for the opportunities it afforded to provide a “public service.” Gradually, the Fort’s interpretive workforce shifted to include more individuals from this latter group as changes in interpretive policy and higher wages attracted a new demographic of applicants who saw opportunities for meaningful employment on public history’s front line.

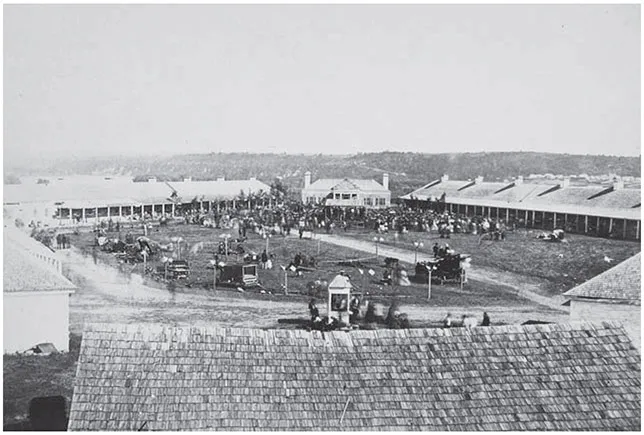

Fort Snelling: Minnesota’s Williamsburg

Throughout its history, the Fort was mostly a quiet post; indeed, its primary purpose in 1858 was to pen sheep.2 Though this army post never entered into the larger historical consciousness of most of the American public, the Fort did play a role in a few key historical events (fig. 1). For example, the enslaved couple Dred and Harriet Scott repeatedly sued for their freedom from 1846 to 1857 on the basis that they had several times lived on free soil—in Illinois and at Fort Snelling, where the couple met (and where they had lived for much of the 1830s). Thus the geographic location of the Fort in “free territory” (per the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, and the Missouri Compromise of 1820) helped lay the groundwork for the United States Supreme Court’s Dred Scott Decision of 1857, which declared that “a negro of African descent, whose ancestors were of pure African blood, and who were brought into this country and sold as slaves,” were not entitled to national citizenship even if living in a free state or territory (and therefore had no legal right to sue in federal courts), and that the federal government had no constitutional basis to prohibit slavery in the territories.3 The Fort also played a significant role in national events during the winter of 1862–63 when the U.S. Army imprisoned approximately 1,700 Dakota Indians (mostly women, children, and elders) just below the Fort’s walls. In the concentration camp at Fort Snelling some three hundred Dakota died as a result of inadequate shelter and poor conditions.4

Figure 1. “The Second Minnesota State Fair at Fort Snelling: Cassius M. Clay Is Delivering the Address,” 1860. Photograph by Moses C. Tuttle. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

Figure 2. “Streetcar passing by the Round Tower, Fort Snelling,” circa 1915, postcard, Acmegraph Company, Chicago. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

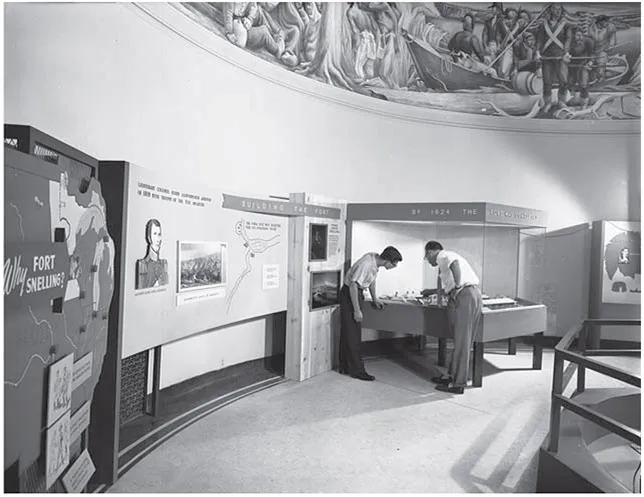

Figure 3. “Visitors Viewing Exhibit at the Round Tower Museum,” circa 1958. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

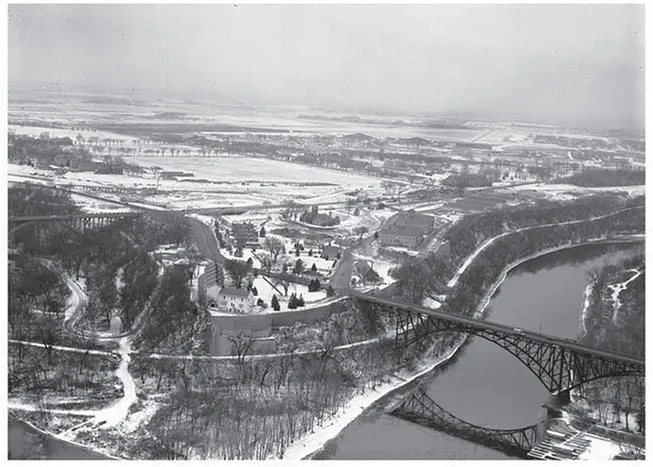

Figure 4. “Aerial View of Fort Snelling,” November 25, 1959. Photograph by St. Paul Dispatch & Pioneer Press. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

From 1866 to 1911, the Fort headquartered the Department of Dakota, which oversaw all military activities in the state of Minnesota and the territories of Dakota and Montana. After World War I, the fort was used as quarters, and one of its four original buildings—the Round Tower, dating to the 1820s—was briefly converted into both a beauty shop and residence (fig. 2). During the 1920s Fort Snelling earned notoriety as the so-called Country Club of the Army because of the extensive polo grounds on its upper post,5 and by the end of the 1930s the old Round Tower, converted from a residence to the “Round Tower Museum,” featured Works Progress Administration murals (fig. 3).6 During World War II, the Fort was bustling again with activity when it served as a Military Intelligence Service Language School and a recruiting, reception, and induction station.7 At the close of the war, however, in 1946, the U.S. military officially decommissioned the Fort as a military post, and the Veterans Administration assumed management.8

Meanwhile, the Fort’s existing structures had long been compromised by a road and bridge that ran through the center of the grounds (fig. 4). In 1956, the four buildings that remained from the early complex were further threatened by proposals to build a cloverleaf turnpike around the Fort’s iconic Round Tower. Weary of urban renewal projects rapidly and dramatically altering the downtown landscapes of the Twin Cities, Minnesotans voiced their displeasure at the prospect of seeing their state’s foremost historical structure blemished by modern freeway construction.

Public outcry led the state to abandon the freeway plans and also to begin discussions on how, in the words of one Smithsonian archaeologist in 1956, “to free the parade ground of the objectionable heavy traffic by way of the Seventh Street bridge, which now bisects the historic nuclear area.”9 Governor Orville L. Freeman, after meeting with representatives from interested state agencies, asked the highway department to redraft construction plans to reroute traffic through a tunnel underneath the historic area of interest, in order to “leave the old fort site free of roads.”10

Traffic rerouting was completed by 1958, at which time the Minnesota Statehood Centennial Commission provided the funds needed for the Minnesota Historical Society to excavate 10 percent of the old post. Excavations unearthed many of the Fort’s original foundations, and positioned the post to become Minnesota’s first designated National Historic Landmark in 1960. But even in the wake of landmark designation and the federal government’s “willingness to transfer the Round Tower and substantial acreage at the Fort to the State for park purposes,” Minnesota still had no established course of action for the preservation, restoration, or interpretation of the historic area.11

In 1963, however, with hopes that Minnesota could enjoy a larger piece of the tourist-economy pie, the Minnesota legislature established the Minnesota Outdoor Recreation Resources Commission (MORRC), whose Fort Snelling Committee lobbied hard to halt proposed new construction on the Fort’s old polo field; state representative William J. O’Brien, who chaired the committee, reflected on how this preservation victory put into sharp relief the many unanswered questions that were “vital to legislative consideration” in order for additional Fort grounds to be put on the path toward eventual preservation or restoration. In partnership with the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS), MORRC established a subcommittee, the Fort Snelling Restoration Committee (FSRC), whose mission was to research and produce a report regarding the projected costs of the Fort’s physical restoration and maintenance, the major uses of the Fort after restoration, and ideas for interpretive programming.12

From the outset, the fifteen professional architects, historians, archaeologists, business leaders, and legislators of the all-male FSRC leaned away from merely preserving the four existing Fort structures as they had changed over time and toward a full-scale restoration and reconstruction.13 As part of their research, the FSRC studied “the more than 50 fort restorations across the country” and paid particular attention to those which “attained the quality that Fort Snelling seeks to achieve,” including Fort Laramie (Wyoming), Fort Michilimackinac (Michigan), Fort Mackinac (Michigan), Fort Osage (Missouri), and Fort Ticonderoga (New York)—restorations that all were host to living history encampments and military pageantry in the 1960s.14 Fort Michilimackinac, for example, hosted its first reenactment pageant in 1962.15 But while the FSRC targeted military historic sites to help them estimate projected staff size and costs, development costs, maintenance costs, attendance, and admissions income, they also took inspiration from other sites.

Fort Snelling historian John Grossman—who developed much of the early interpretive programming materials—noted that, “Program ideas and precedents were borrowed from places such as Williamsburg, Virginia, Old Sturbridge Village, Massachusetts, and Fort York and Fort Henry, Ontario, where personnel have had experience in interpretations. The people at Fort York were particularly helpful with military training, equipment, and demonstrations.”16 Likewise, in remarks to the Minnesota Planning Association in 1965, FSRC chairman William J. O’Brien began his presentation by showing a film about the restoration and reconstruction of Colonial Williamsburg—the Rockefeller-funded project that aimed to recreate (a white-washed vision of) Virginia’s colonial capital through restoration and reconstruction. “That’s how it’s done, being done at Williamsburg,” noted O’Brien to the group of Minnesota planners: “Fort Snelling is Minnesota’s Williamsburg.”17 In 1965, the FSRC’s report and recommendations persuaded the legislature to appropriate $200,000 from the natural re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Customer Service Superstars

- Part I: Public History’s Emotional Proletariat (1960–1996)

- Part II: Historic Fort Snelling’s Front Line (1996–2006)

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Index