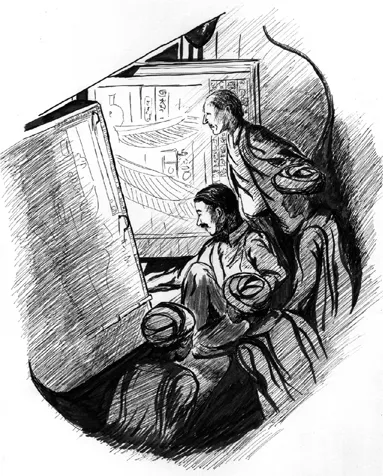

“Can you see anything?” asked Lord Carnarvon. “Yes, wonderful things,” answered Howard Carter as he gazed upon the contents of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 (Figure 1.1). The methods used by Howard Carter in the early twentieth century and those employed by twenty-first century archaeologists differ greatly. Not only are the methods used divergent from a century ago, so are the motivations behind archaeological research. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century seekers of ancient cultures too often sought to increase their own fame and fortune via their “archaeological” discoveries; artifacts and sometimes portions of entire buildings were whisked away to a foreign land for display and study. The objects themselves were deemed the vehicles by which ancient cultures would be revealed.

Archaeology in the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries has changed immeasurably from those early days. While artifacts and features remain important, it is their context that is recognized as the vehicle into the past. This, combined with scientific methods and anthropologically driven interpretive frameworks, has allowed archaeological researchers to skillfully reconstruct past cultures in sometimes surprisingly intimate detail. What is it that inspires archaeologists to undertake the challenge of reconstructing the past? Furthermore, what responsibilities are embedded within these challenges? This opening chapter seeks to answer these questions as well as another: why is the archaeology of religion important? A final section describes the themes and subjects found in succeeding chapters.

Why Archaeology and Why Religion?

Why should archaeology be considered an important field of study in the larger scheme of this increasingly globalized world? Many suggest that the most basic reason to study the past is to better understand the present, even to avoid “making the same mistakes twice.” One archaeologist suggests it is informative to use the present as an interpretive tool for the past (Binford 1983), creating a connective loop of human experience. Humans seem to be curious about what their predecessors did; and archaeology seems to be the discipline best-suited to satisfy that curiosity. The answer to the question of why archaeologists do what they do is linked with the answer to why archaeology is considered a legitimate discipline for study: human curiosity. However, it is a curiosity paired with a desire to embark on the unique challenge of compiling disparate clues, derived from multiple sources, and using them as the foundation—usually one missing many footings—to recreate the structure of an inhabited past. The archaeologist’s role, most simply stated, then, is to offer informed interpretation of the past.

Figure 1.1. Carter and Carnarvon look into King Tut’s Tomb. (M. J. Hughes)

In recent years archaeologists have made tremendous efforts to include some discussion of the target culture’s religious beliefs. The reasons for this are both cultural and practical. On the cultural end, archaeologists have long known that the linkages between religious belief and daily life are indiscernible in many, if not most, cultures. However, the tools, methodologies, and interpretive frameworks to illuminate past belief systems have been longer in the making; while far from perfected, using the methods of scholarly inquiry outlined in this book, bolstered by elements of psychology, sociocultural anthropology, and religious studies (Bertemes and Biehl 2001), archaeologists have proceeded in their endeavors to describe ancient beliefs.

A second reason the archaeology of religion has grown in importance is due to increasing levels of cultural sensitivity by archaeologists. Every discipline has its standard of ethics unique to that field. Sociocultural anthropology has a strict code of ethics guiding the field anthropologist’s behaviors and what it considers appropriate actions regarding informants in the cultures under study. However, archaeologists have come to realize that, just like anthropologists, they also deal with the living every time they are in the field excavating a site, whether with local residents or the descendants of those cultures they investigate. In those settings they are bound by the same ethics as any sociocultural anthropologist. Even those working in their home countries must remember they are a guest in someone else’s place, whether it is in the next-door neighbor’s field or in a far-flung state or province.

Practically speaking, archaeologists are encountering past religions on a frequent basis. The combination of national infrastructural development and an increasing interest in cultural resource management (CRM) has led to the growth of a CRM field that undertakes archaeological investigation of many places destined for large-scale building projects. Many countries have enacted regulations requiring their own versions of CRM work to be accomplished prior to the commencement of a project, or to be performed should cultural resources be discovered during a project. In 2005 a Turkish government project to build an underwater tunnel linking the European and Asian sides of Istanbul was virtually halted by the discovery of a Byzantine port, and a large-scale excavation was launched. The building project, including an intended subway, has been revamped to accommodate the excavation of this enormous port and the planning of a new museum. Such stories are becoming increasingly common as nations take a greater interest in preserving their cultural past. As more excavations are undertaken, archaeologists face a greater need to properly excavate, and interpret, sensitive cultural materials, particularly those pertaining to belief systems. Additionally, a growth in the worldwide practice of archaeology has created a priority to revisit, and reinforce, ethical concerns within the field.

Ethics, Archaeology, and Religion

When archaeology and ethics are mentioned in the same breath, the first thought centers on the serious issues of site looting, the black market trade in stolen antiquities, and the inappropriate curation and display of cultural objects (Vitelli 1996; Zimmerman, Vitelli, and Hollowell-Zimmerman 2003). However, embedded within the archaeology of religion are some further, field-specific, ethical concerns that must be considered.

The Ethics of “Proving” the Past

Those undertaking archaeological investigation must maintain absolute objectivity when interpreting the material culture within its context, particularly if there is other evidence available that pertains to the same culture, time period, or region. What has occasionally proved to be too tempting, particularly for archaeologists in earlier centuries, was to “prove” the past according to written records. This was particularly prominent in the field known as Biblical Archaeology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Important archaeological material was discarded because it didn’t “fit the texts” and thus contradicted what was assumed to be true based on biblical accounts (Bergquist 2001; Insoll 2001). Archaeologists must certainly be familiar with any written records pertaining to their research area, and should even be guided by such records, but they must also recognize when the data derived from the material culture diverges from that written in the texts. The material culture is the purest record of the past; the discipline of archaeology, therefore, must maintain that purity as much as possible in presenting that past.

The Sacred Past

As travelers, when we enter a building or locale sacred to another culture, we think nothing of abiding by the behavioral codes practiced in that culture. Those who don’t are considered rude and disrespectful. What were the behavioral codes associated with sacred places and things in the past, and how can we as archaeologists abide by them and still do our work? In general, these are unanswerable questions because in order to abide by behavioral codes, an archaeologist must discern what they were; and the method by which he or she learns them (i.e., by excavating sacred places and things) is almost certainly a violation of those codes. Where is the happy medium between the scientific investigation of the past to inform the present, and preservation of the sacred past by leaving it undisturbed?

For now, archaeologists are guided by the living descendants of past cultures. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) mandates behavioral codes for any archaeologist dealing with Native American sites, especially regarding any aspect of the material culture that may be considered “sacred.” In the Middle East, archaeologists are cautioned to be cognizant of burials on high mound sites, especially if they are quite close to the surface. The reason for this is that often Muslim families will decide to bury a loved one not in the local cemetery but on a high place, with the deceased facing east (or toward Mecca). It is not only illegal, but inappropriate, to excavate such burials, and if they are discovered on an archaeological site, that area is left alone and the presence of the burials made known so that future excavators can also leave them undisturbed.

These are but two examples of principles regarding the proper treatment of sacred objects and places that help guide archaeologists in the field. Note, however, that in both cases these guidelines were set out by descendants of those past cultures. At issue, then, is how can archaeologists be guided when there are no descendants to set down rules? We must adhere to our own internal ethics while still striving to present, in objective fashion, the results of our discoveries to the public. It is an imperfect solution to the problem of appropriate behavioral codes and the sacred past—but the best we have nonetheless. Its success depends on the professionalism of the archaeologist and the appropriateness of the display of the retrieved material culture (i.e., in a museum or other public venue). If both of these factors are satisfactory, then the beauty of that ancient culture and its beliefs will themselves rekindle the appropriate behavior in everyone who sees them.

Cultures and Their Beliefs in Worldwide Context

Which cultures should be explored in a book on the archaeology of religion? Ideally, all of them—but of course this is an impossible task. Inevitably someone’s favorite ancient society will be absent from the coming chapters (this is true for the author herself, who painfully decided that the religions of Neolithic and Chalcolithic Anatolia were a bit too remote for presentation). Certain discussions are a must, given their popularity: the Egyptians, the Aztecs. Other chapters focus on lesser-known but equally fascinating past belief systems (Great Zimbabwe, Neolithic Southeast Asia). The author, and those who choose to read this book, can perhaps be comforted by the fact that there are a growing number of excellent treatments on the archaeology of religion (see Chapter 2), and it is certain that in some of these, one’s favorite past culture and religion are profiled.

This volume seeks to go beyond simply presenting a shopping list of past cultures and their religions, interesting though that may be, to examine what religions can tell us about human culture as a whole. A few theoretical frameworks, introduced here and explored in more detail later (see Chapter 2), offer some methods for interpreting past, and present, religions as lenses on the prism of belief systems and how they function in society.

In general, four interpretive frameworks will be employed, to greater or lesser extent, as approaches for understanding the cultures and belief systems explored throughout the book. The first, and perhaps the most often evident, is the model that dictates the reflective nature between religion and culture. The overall structure of a society, as well as its most crucial institutions, values, and ideals, can often be clearly observed in its belief system, in effect mirroring the culture. A second, related model examines the interrelationship between religion and environment. A culture is most certainly shaped by the environment in which it is located, and so too is its religion. In many cases it is possible to discern how important a healthy ecological balance is to a culture by examining the significant focus on environment in the belief system.

A third interpretive framework sees a more proactive use of religion as a powerful method to control society. This becomes particularly prevalent in more complex societies when ruling elites seek to keep a tight reign on their p...