Chapter 1

Introduction

The archaeology of world religion

Timothy Insoll

Definitions and objectives

The archaeology of world religions is a vast subject, and one which it might seem foolhardy to attempt to consider within the confines of an edited volume composed of nine chapters, three of which are considerably shorter commentaries. However, this volume does not claim to be universal, rather it aims to examine the relationship between, and the contribution archaeology can make to the study of, what are today termed world religions, through focusing upon the examples of Judaism, Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism. This raises a couple of questions. First, why world religions in particular? Although there is no shortage of archaeological studies of elements of world religion in ‘mainstream’ archaeological literature there appears to be a gap with regard to an overall consideration of archaeology and world religion (a notable but dated exception is a namesake volume [Finegan 1952] which attempts to be all-inclusive but is now rather dated). There is also a certain imbalance in the mainstream literature (the focus, at least, of this introductory chapter) in favour of Christian archaeological remains (see for example Frend 1996, Platt 1987, Blair and Pyrah 1996), probably a reflection of the bulk of work having been undertaken in Europe, which is also the centre of many of the relevant archaeological journals and publishing houses. Thus applicable studies of Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, or Jewish archaeology or archaeological material tend to be confined to specialist journals and other publications, though to be fair this imbalance has begun to be rectified of late (see for example Barnes 1995, Insoll 1999a).

Second, it could be asked why these religions in particular? The examples chosen are certainly not meant to be exclusive, but merely reflect the interests and specialisations of the contributors to the volume. Third, what constitutes a world religion? This is in fact something which is frequently neglected in the literature. Is it number of adherents? Is it geographical spread? Is it length of time in existence? Is it unity in practice and doctrine? Is it Universality, or consideration by their adherents to be proper to all mankind? (Sopher 1967). Is it the existence of a notion of salvation, or because they rest on a basis of written scripture? (Bowie 2000:26). Is it all, some, or none of these, or many other criteria which could be listed? Answers to these questions are elusive, as they are, indeed, to answering the question of what is religion itself, an issue which has been the subject of ‘seemingly endless debate’ (Clarke and Byrne 1993:6). One could turn to the simplistic definitions of religion listed in major dictionaries (see for example Renfrew [1994:48] for such an application), but such definitions are by their very nature so general as to be of little use.

No answer is to be provided here, though having said this, Durrans’ (2000:59) recent definition of religion is as useful as any other, ‘a system of collective, public actions which conform to rules (“ritual”) and usually express “beliefs” in the sense of a mixture of ideas and predispositions’. Likewise, to endeavour to neatly differentiate religion from one of the archaeologist’s favourite categories, that of ritual (see below), is a major undertaking. Indeed, to attempt a definition of either world religion or religion/ritual itself is beyond the confines of this introductory chapter, and of the volume. This might be taking the easy option, but the author is unapologetic for this, and it is merely noted that with regard to the examples chosen, geographical spread and thus an extensive archaeological legacy tie these five religions loosely together as much as anything else. Archaeology is the concern, and is witnessed by the material record of Judaism in Israel and the Diaspora, Buddhism in south and south-east Asia, and more recently, elsewhere in the world, Hinduism likewise, Islam within the borders of the Muslim world as usually defined from Morocco in the west to Indonesia in the east, but also, increasingly, worldwide, and finally, that of Christianity similarly spread across the continents.

Definitions aside, what then does this chapter attempt to achieve? First, a possible structure of study for the archaeology of world religion will be considered. Whether the archaeological study of world religion can draw upon methodologies and concepts developed elsewhere in the study of religions, notably the broad field encompassed by history of religions, or whether there is little to be gained from adopting explicit theoretical approaches from such sources. Second, the approaches which have been adopted to the archaeology of world religion will be briefly outlined, again with the proviso added that within the limits of circa 10,000 words this cannot be considered exhaustive. This section will essentially be divided into two parts—what could be termed negative aspects regarding archaeology and its application to the study of world religion, and in contrast, the positive aspects as well. Finally, the papers themselves will be introduced, and the perceived similarities and differences in how they might be approached by archaeologists will be examined.

An approach to the archaeology of world religion?

Archaeological approaches to religion are remarkably piecemeal, at least in the UK, ad hoc almost, with the subject being considered as and when necessary, with few serious attempts at examining approaches to the archaeological study of religion overall. Conferences, for example, have been occasionally organised with archaeology and religion as their focus, the Sacred and Profane meeting in Oxford (Garwood et al. 1991) being notable, or the conference held in Cambridge in 1998 from which these papers emerged being another (see Insoll 1999b). Other examples of approaches to archaeology and religion within the ‘mainstream’, outside of a conference format, vary, with one of the most famous of these being Christopher Hawke’s ‘ladder of inference’, whereby ritual/religion was placed as one of the most inaccessible rungs in the interpretative process, compared to, for instance, economy (see also Parker Pearson in this volume). The realisation that religion/ritual might be of importance to archaeologists in general is sometimes accredited to proponents of the ‘New Archaeology’ (see for example Demarest 1987). David Clarke (1968), for example, was influential in this respect, seeing religion ‘as a distinct information subsystem’ (P.Lane pers. com.), as important as economy or social organisation in maintaining equilibrium in systems/ cultures. More recently Renfrew (1994) has approached the archaeology of religion within the framework of cognitive archaeology (Renfrew and Zubrow 1994). He draws upon the ideas of, among others, Rudolf Otto (1950) and his notion of the numinous, of religious ‘essence’ (discussed in greater detail below), before considering how religion/ritual might be recognised in archaeological contexts.

However, Renfrew’s approach towards religion is general, as the title of his paper, ‘the archaeology of religion’, implies. The components of religion, world religions, for example, have been little considered in terms of archaeological approaches that might be employed to further their study. This lacunae in approaching world religions is apparent in the work of other archaeologists who have approached religion/ritual from a theoretical, or what could be termed a ‘dedicated’, perspective. The Sacred and Profane conference referred to previously (Garwood et al. 1991) is heavily focused towards prehistory and ‘ritual’ rather than protohistorical or historical archaeology as might fall within the domains of the study of world religion. In fact, prehistory would in general appear to be the slightly more favoured partner when it comes to devoted mainstream archaeological research and publication directed at investigating religion/ritual (see for example Gimbutas 1989, Gibson and Simpson 1998, Green 1991, Burl 1981).

A further and well-known example of a dedicated mainstream consideration of religion is provided by the Sacred Sites, Sacred Places volume (Carmichael et al. 1994), one of the volumes in the One World Archaeology series derived from the World Archaeological Congress. Coverage in this is more even than in the Sacred and Profane volume previously considered, yet besides the introductory papers (see for example Hubert 1994), the ensuing case studies are particularistic in focus, a further characteristic of relevant research discussed below. This weakness in archaeological theory towards the investigation of religion in general is something remarked upon by Garwood et al. (1991:v) who refer to it as an ‘extraordinary neglect…which must be addressed’. These are admirable sentiments and even today, too often, material that is unusual or eludes interpretation is placed within that convenient catch-all interpretative dustbin of ritual. A practice which is easy to justify as the necessary debate over the terminology, methodology and theory of archaeology and religion/ritual has still to be seriously initiated.

Anthropology, in contrast, would appear to be more mature in its theoretical approaches to religion, a debate which has continued for some years and a process charted, in part, by Parker Pearson (this volume). Anthropology also benefits from several convenient summaries of approaches to religion which have been employed within the discipline (see for example Evans-Pritchard 1965, Saliba 1976, Morris 1987, Bowie 2000). This debate is something which archaeology has lacked to date (Insoll forthcoming). Yet this does not mean that anthropologists over the course of the past 150 years or so have worked out the perfect methodological and theoretical approaches to religion, they have not. The excesses of the early evolutionary approaches to religion, exemplified by, for example, Frazer (1890), Spencer (1876), and Tylor (1871) might be past, and a much more mature approach in evidence, but a dichotomy still appears to exist. To quote Morris, anthropology texts ‘largely focus on the religion of tribal cultures and seem to place an undue emphasis on its more exotic aspects’ (1987:2). So-called tribal religions are thus split up into phenomena—myth, witchcraft, magic and so on—whereas in contrast, as Morris also notes (ibid.: 3), world religions are treated according to a quite different theoretical framework whereby they are treated as discrete and distinct entities, such as ‘Buddhism’ or ‘Islam’. Admittedly, anthropological approaches to the study of religion are more complex that this, as Parker Pearson indicates below, but the important point is that even after many metres of bookshelves-worth of relevant material have been published and much introspective disciplinary soul-searching completed, an ideal approach has yet to be adopted, and in all probability never will.

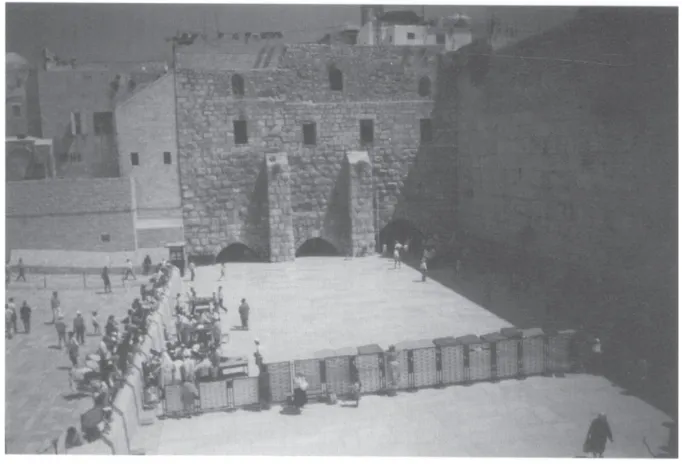

Where then does this leave the archaeology of world religion as regards theoretical perspective? Put simply, there is not one. As already indicated, archaeological studies of religion with an explicit theoretical focus are few and far between, whereas innumerable studies of actual material exist in both mainstream and more specialised media. These are studies completedat a variety of levels, local, regional, focusing upon component parts of religious practice such as pilgrimage (Figure 1.1), or at the total religious scale (Rodwell 1989, Gilchrist 1994, Graham-Campbell 1994, Frend 1996, Insoll 1999a), but lacking a common theoretical approach. Even within this volume, edited by one person with fairly clear views as to the desired end product, the disparity in approaches is readily apparent. Yet this is not necessarily a bad thing, and it is not the presumption here to try and develop a theoretical approach for the archaeology of world religion. This is patently an absurd proposition, but it is possible, perhaps, to point to a few useful avenues of investigation, which other better qualified scholars might then explore.

Figure 1.1 The Wailing or Western Wall in Jerusalem, with above it the Dome of the Rock—the foci of pilgrimage in two world religions, and also the focus of much controversy (photo T.Insoll)

Primary amongst these would appear to be the acknowledgement that a useful source of material which might be drawn upon to begin to consider relevant approaches exists within the fields of study encompassed within history of religions, comparative religions, or what is sometimes rather forbiddingly referred to in its untranslated (and untranslatable) German as Religionswiffenschaft. This is defined by Hinnells (1995:416) as the academic study of religion apart from theology, and was introduced by Fredrich Max Müller (1823–1900). In many ways the certain degree of untranslatability of Religionswiffenschaft into English reflects the dichotomy of archaeology as a discipline in itself, with Religionswiffenschaft as a term in German covering both science and humanities, a meaning largely lost in translation (Hinnells ibid.). This multi-disciplinary aspect of what we might refer to as history of religions might be useful as it draws in many different aspects of research, conveniently defined by Saliba (1976:25) as, ‘the study of the origin and development of religion—embracing all the world’s religions past and present in one single field, as one whole phenomena evolving in time’. This idea of unity is exciting and might help in breaking down many of the particularities all too often evident in relevant archaeological research, and thus help us to move beyond merely description or the listing of facts. These are faults not unique to archaeology but something remarked upon by Evans-Pritchard with regard to comparative religion itself, a discipline which he stresses, ‘must be comparative in a relational manner if much that is worthwhile is to come out of the exercise. If comparison is to stop at mere description—Christians believe this, Moslems (sic) that and Hindus the other…we are not taken very far towards an understanding of either similarities or differences’ (1965:120).

Within the history of religions, study is encompassed under a number of sub-disciplines, psychology of religion, philosophy of religion, sociology of religion, phenomenology of religion, history of religion (lacking plural). Why not archaeology of religion as well? Demarest refers to archaeology and the study of religion maintaining ‘a close but uneasy relationship’ (1987:372); should archaeology be further integrated within the study of religion forming perhaps another component part of history of religions-type approaches or is it too much to see archaeology reduced to a micro-category and subsumed within a macro-heading such as history of religions? It depe...