eBook - ePub

Empire and Local Worlds

A Chinese Model for Long-Term Historical Anthropology

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Mingming Wang, one of the most prolific anthropologists in China, has produced a work both of long-term historical anthropology and of broad social theory. In it, he traces almost a millennium of history of the southern Chinese city of Quangzhou, a major international trading entrepot in the 13th century that declined to a peripheral regional center by the end of the 19th century. But the historical trajectory understates the complex set of interrelationships between local structures and imperial agendas that played out over the course of centuries and dynasties. Using urban structure, documentary analysis, and archaeological artifacts, Wang shows how the study of Quangzhou represents a Chinese template for civilizational studies, one distinctly different from Eurocentric models propounded by such theorists as Sahlins, Wolf, and Elias.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Empire and Local Worlds by Mingming Wang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

To make my narrative more concise, I have chosen to approach the larger story of Quanzhou by way of organizing available materials around a smaller genealogy. This is a history of an institution of spatial organization, that of pu and its Ming-Qing version pujing. The changing institutions specified by the terms of pu and, later, pujing were core to the making of the outer form and the inner dynamics of place and landscape in imperial Quanzhou. It was central to both the imperial arts of control, to the regional urban elites’ strategic tactics, and to popular religious/cultural practices and conceptions. It was installed in the city in the thirteenth century, during Quanzhou’s commercial heyday, and evolved into, in terms of its political and social roles as well as its cultural conceptions, diverse patterns of ritual landscape and social activity in late imperial dynasties of the Ming and the Qing. After having spent more than a decade studying them, I have found that changing spaces of pu and jing reflected most clearly the changing nature of politics, commerce, public life, and landscape in historical Quanzhou.

First, let me provide a brief explanation. The main character in the word pujing is pu. Pu, originally meaning “ten li,”1 is used in both classical Chinese and Quanzhou’s local dialect—which is locally perceived to be one of the rare intact linguistic relics of the former—to mean also “wards,” “stations,” “shops,” “brigades,” “offices,” or “watch posts.” It is, in its older and narrower sense, the word for guarded focal points in the place hierarchy of the empire. At the same time, pu also refers, in its extension from administrative and military nodal points, to “low-level places,” for example, “villages,” “neighborhoods,” “communities,” and “guarded areas” (especially, areas guarded by gods and their “soldiers”).

There is no character that means exactly the opposite of pu, but the above-mentioned connotations of pu, in one way or another, contrast with the greater landscapes of civilization and supralocal spatial entities. Paradoxically, as such, pu was, in the very beginning of its existence, devised to accomplish official “supralocal” tasks. Unlike maritime trade from Quanzhou, which came to the attention of the court only after having created an attractive channel of resources, the institution of pu was installed with an explicit political rational by the court. Pu in this sense were spatially segmented units for networked information transmission and superintendent local control.

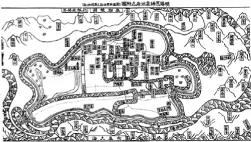

Originally termed putu [wards and charted areas], the institution of pujing first emerged as a system of territorial administration during the Yuan (1271–1368), which replaced the Song fangxiang system of urban districts. Chen Si Dong, a prominent local historian, wrote in his extremely succinct discussion to argue that pujing emerged as a system of urban neighborhood division in the late thirteenth century.2 According to him, during the thirteenth century, the magistrate divided Quanzhou into of 36 territorial units called pu [wards], which were in turn integrated into three urban boroughs called yu. By the Ming, the term jing [precincts] had been added to describe subward divisions of precincts. Around 1700, another yu (borough) was added, and Quanzhou then consisted of four urban districts. In the mid-eighteenth century, two more pu were added, thus making a total of 38 pu divisions of the city.

Obviously, the core of pu and jing was an institution of spatial organization. Relevant to this, in historical and anthropological studies of China, two sorts of approaches have been advanced: (1) G. William Skinner’s approach to the hierarchies of “central places” as functionally related networks of commerce, transportation, and imperial local administration3 and (2) Ch’u T’ung-tsu,4 Brian McKnight’s,5 Timothy Brook’s,6 Michael Dutton’s,7 and many others’ approaches to regional administration and surveillance. In local contexts, the aspect of Chinese spatial organization as shown in the approach of imperial field administration is central to pu and pujing’s official designation.8 But in the city of Quanzhou, pu and pujing did not merely signify an institution of “central place” and local administration. In fact, while the concepts of pu and jing continued to serve as apparatuese of imperial local administration, already by the early Ming pujing had been re-invented as a radically different system from the previous prototype of local administration in the Yuan. Merged with a set of imperial regulations of sacrifice and conduct consciously devised for the people to obey, in the Ming pujing became a space for disciplining and civilizing. Even more dramatically, starting in the mid-Ming, the territorial divisions and sacrificial rituals of pujing were re-appropriated into territorial worship practices that consisted of ritual activities that were by that point understood as “licentious cults” [yinci], oppositional to the Ming’s official notion of civilization.

The transformation of pu from a kind of bureaucratic apparatus in the Yuan into Ming civilizing rituals and then, by the mid-Ming, into local communities of popular “licentious cults” suggests a complex history whose spirit is apparent in the folklore of the Carp. I will dwell on this history in greater detail.

When I began to focus on studying Quanzhou, I had been trained as an anthropologist. I was working toward an approach to the mystics of the State and regional culture as seen in the co-existing calendars and spectacles of ritual activity.9 Since then, I have been fascinated with the politics associated with the concepts of pu and jing. Ultimately, the process whereby the same institution absorbed different functions has struck me as important. I have sought to bring it into the forefront of the anthropology of “Chinese territorial cults,” which has been the focus of such anthropologists of China as P. Steven Sangren10 and Stephan Feuchtwang.11

Had Sangren and Feuchtwang gone to study Quanzhou, they would have found that pujing provided a good example in which to examine, from an “emic” perspective, conceptions of social space in which peripheral small places and their own cultural patterns are distinguished from and related to imperial cosmology. “The production of culture” (Sangren) and the “bureaucratic metaphor” (Feuchtwang) are surely two guises through which the dialectics of empire-locality linkage are displayed. But through my own ethnographic and historical inquiries, I have found the concepts of “political economy of symbols” and “bureaucratic metaphor” inadequate.

Instead, what has intrigued me has been the ways in which pujing has been involved in multiple consciously organized dynastic and regional campaigns to bring local society back onto the “right track” of civilization. The purpose of these campaigns was the assertion of orthodox visions of order, but the result of these campaigns was far from successful. Thus, in the Qing Dynasty, two more efforts were made to turn the “licentious cults” into something that would be useful to imperial rulers and regional elites, in which what was associated with pu and jing was enhanced, in an open manner, as spectacles of regional vitality.

I began to study Quanzhou in the early 1980s. The first piece of work that I produced concerned the emergence of the harbor.12 During the late 1980s and the early 1990s, as an anthropologist, I made both ethnographic and historical investigations into the city’s public life as seen particularly in the practices of pujing. The emergence of the harbor and the invention of pujing took place in two different episodes of history, and they represented two different lines of development, the former economic and the latter bureaucratic and civilizational. The rise of the seaport in Quanzhou signaled the early expansion of regional prosperity. Institutions and politics related to the concept of pu were invented during the Song and the Yuan, when Quanzhou came into its prosperous age. But it was not a commercially and culturally liberating force. On the contrary, it was limiting and restrictive, ironically during Quanzhou’s most prosperous period. We should not easily define such changing “places” in terms of a system of politically restrictive locales. In the history of pu, what is significant is a set of processes that vividly displays the active interplay between culture and commerce, integration and segmentation, civilization and the “wantonness” of popular cults, order and chaos, and state power and local propensity of energy. These processes are also reflected in the folklore of the Carp, which is indeed the very condensed story of the city. For me, such a set of processes, which were apparently connected with certain sets of relationships, provide a good example with which to illustrate the alternating pattern of political culture not only in the city of Quanzhou but also, by relation and implication, in imperial China and its world as a whole.

Pu, Pujing, and the History of Quanzhou

In the central portion of this book, I concentrate on:

- The institutional evolution of pu as an administrative apparatus in the thirteenth century;

- The administrative, ideological, and cultural perfecting of pujing in the early Ming between the late fourteenth century and the early fifteenth century;

- The transformation of official pujing institutions into popular religious practices in the middle and late Ming, between the late fifteenth and the seventeenth century;

- The imperial projects to re-enhance the energy of local worlds of pujing in the late Ming and the early Qing for two different ends:

- a. The installation in the late Ming the communal pact system, which demonstrated to be not quite effective;

- b. The installation of the “conferences of gods” by regional power elites, which yielded an unintended outcome—extensive feuds that could not be resolved by the court or the regional power elites;

- The continued innovations surrounding the institution of pujing between the late eighteenth century and the nineteenth century in folklore and by the urban elite, and regional efforts to transcend local boundaries near the end of the nineteenth century.

The discussions that follow are historically specific. After Chapter 1’s elaboration of our theme and its significance, Chapter 2 provides an historical outline of pre-Ming political economy and culture. I draw on historical studies to suggest a relationship between the coming of the age of commerce and the changing characteristics of the empire. A special emphasis is placed on the location of Quanzhou in the imperial and regional systems of hierarchical places whose history came much earlier than local history. Juxtaposing local history with imperial cosmology, I also draw and bear on Hill Gates’s theoretical work, which views the Chinese tributary mode of production as central to the empire.13 Gates, like her forerunner, the Marxist anthropologist Eric Wolf,14 identifies the empire as characterized by a precapitalist mode of production. By contrast, I have argued strongly that this “Oriental empire” has its own cosmological structure of relationship. In historical Quanzhou, to become a central place in the empire, people first had to struggle to enter the imperial zoning of the world. But at the same time, as a marginal group, they also benefited from Quanzhou’s liminal position. Situated between civilization and its outer realms, Quanzhou was able to advance into its heyday.

Except for Chapter 2’s background history of the city, my study focuses on the story of pu and jing, whose multiple roles were manifest and transformative during the late imperial dynasties of the Yuan, Ming, and Qing (1270–1896) (for purpose of giving a clearer definition of the foundation of imperial order, I also touch on the pre-Yuan periods).

In the beginning, pu’s designated function was social control, information gathering, and document transmission. But by the early Ming, the territorial system had been deployed by officialdom to fulfill more tasks. To the Mongol colonial field administration of the Yuan, a new function was given to this institution. It became a means of symbolizing the presence of imperial power and cosmology in the local places. Gradually, the perfected Ming system of pu and jing, whose financial burden and social problems gradually came to trouble the government, was to be left in the hands of local inhabitants who, as socially and economically differentiated groups, reformed this political and cosmological order through ceremonial appropriations, storytelling, and daily practices. Through these processes, pujing evolved into a variety of things. Chiefly, as I argue, it was reshaped into a local institution of territorial guardian-gods’ birthday festivals, in which official spatial conceptions were challenged.

Documentary materials in this subject are scarce. But taken as an analytical whole, they confirm that pujing played an important role in the public life of local inhabitants of Quanzhou during the Ming and the Qing. The significance of writing this history is apparent: Although there have been studies of imperial order and macro-scale political life in imperial Chinese cities, materials concerning the characteristics of “low places,” such as pu and jing in urban Chinese communities, are rare as are materials that offer direct testimony of what the “dead interviewees” practiced, witnessed, and inscribed politics and customs. In themselves they reveal a historical pattern, in which a system of delineated neighborhoods was conjoined with other sources of social and political dynamics as a cycle of order and/or chaos.

The origination, authorization, transformation, and restrengthening of pu can be associated with the changes occurring in the broader context of Chinese society. Particularly, as I show in Chapter 3, during the Yuan, after serving in the Song as a system of courier-post networks, pu was inserted into local society by way of the Mongol colonial enterprise of neighborhood control, household registration, and economic expl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Transliteration and Bibliography

- Prelude

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Carp: Empire and the Culture of Commerce, 712–1368

- 3 Casting the Net: Pu and the Foundations of Local Control, 960–1400

- 4 Pujing and the “Civilizing Process” of the Ming, 1368–1520

- 5 Heaven on Earth: Pujing and the Worlds of Worship Platforms

- 6 Local Worlds on the Margin, 1400–1644

- 7 Unorthodox Cults and the Expulsion of Demons, 1500–1644

- 8 “Congregations of the Gods,” Rule of Division, 1644–1720

- 9 Pujing Feuds, 1720–1839

- 10 The Ceremonial Redemption, 1840–1896

- 11 Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Footnotes