This book is a warning against recent developments in the field of crime control. The theme is simple. Societies of the Western type face two major problems: Wealth is everywhere unequally distributed. So is access to paid work. Both problems contain potentialities for unrest. The crime control industry is suited for coping with both. This industry provides profit and work while at the same time producing control of those who otherwise might have disturbed the social process.

Compared to most other industries, the crime control industry is in a most privileged position. There is no lack of raw-material; crime seems to be in endless supply. Endless are also the demands for the service, as well as the willingness to pay for what is seen as security. And the usual industrial questions of contamination do not appear. On the contrary, this is an industry seen as cleaning up, removing unwanted elements from the social system.

Only rarely will those working in or for any industry say that now, just now, the size is about right. Now we are big enough, we are well established, we do not want any further growth. An urge for expansion is built into industrial thinking, if for no other reason than to forestall being swallowed up by competitors. The crime control industry is no exception. But this is an industry with particular advantages, providing weapons for what is often seen as a permanent war against crime. The crime control industry is like rabbits in Australia or wild mink in Norway – there are so few natural enemies around.

Belief in being at war is one strong driving force behind the development. A general adaptation to industrialized ways of thought, organization and behaviour is another. The institution of law is in a process of change. The old-fashioned symbol was Lady Justice, blindfolded, and with scales in her hand. Her task was to balance a great number of opposing values. That role is threatened. A silent revolution has taken place within the institution of law, a revolution which provides increased opportunities for growth within the control industry.

Through these developments, a situation is created where a heavy increase in the number of prisoners must be expected. But there are counter-forces in action. As will soon be documented, enormous discrepancies in prison figures exist between countries otherwise relatively similar. We are also confronted with “inexplicable” variations within the same countries over time. Prison figures may go down in periods where they, according to crime statistics, economic and material conditions, ought to have gone up, and they may go up where they for the same reasons ought to have gone down. Behind these “irregular” moves, we find ideas on what is seen as right and fair to do to other beings, ideas which counteract “rational” economic-industrial solutions. The first chapters of this book document the effects of these counter-forces.

My lesson from all this is as follows: In our present situation, so extraordinarily well suited for growth, it is particularly important to realize that the size of the prison population is a normative question. We are both free and obliged to choose. Limits to the growth of the prison industry have to be man-made. We are in a situation with an urgent need for a serious discussion on how large the system of formal control can be allowed to grow. Thoughts, values, ethics – and not industrial drive – must determine the limits of control, the question of when enough is enough. The size of the prison population is a result of decisions. We are free to choose. It is only when we are not aware of this freedom that the economic/material conditions are given free reign. Crime control is an industry. But industries have to be balanced. This book is about the drive in the prison industry, but also about the counter-forces in morality.

Nothing said here means that protection of life, body and property is of no concern in modern society. On the contrary, living in large scale societies will sometimes mean living in settings where representatives of law and order are seen as the essential guarantee for safety. Not taking this problem seriously serves no good purpose. All modern societies will have to do something about what are generally perceived as crime problems. States have to control these problems; they have to use money, people and buildings. What follows will not be a plea for a return to a stage of social life without formal control. It is a plea for reflections on limits.

Behind my warning against these developments lurks a shadow from our recent history. Studies on concentration camps and Gulags have brought us important new insights. The old questions were wrongly formulated. The problem is not: How could it happen? The problem is rather: Why does it not happen more often? And when, where and how will it happen next time?1 Zygmunt Bauman’s book Modernity and the Holocaust (1989) is a landmark in this thinking.

Modern systems of crime control contain certain potentialities for developing into Gulags, Western type. With the cold war brought to an end, in a situation with deep economic recession, and where the most important industrial nations have no external enemies to mobilize against, it seems not improbable that the war against the inner enemies will receive top priority according to well-established historical precedents. Gulags, Western type will not exterminate, but they have the possibility of removing from ordinary social life a major segment of potential trouble-makers for most of those persons’ lives. They have the potentiality of transforming what otherwise would have been those persons’ most active life-span into an existence very close to the German expression of a life not worth living. “. . . there is no type of nation-state in the contemporary world which is completely immune from the potentiality of being subject to totalitarian rule,” says Anthony Giddens (1984, p. 309). I would like to add: The major dangers of crime in modern societies are not the crimes, but that the fight against them may lead societies towards totalitarian developments.

It is a deeply pessimistic analysis I here present, and as such, in contrast to what I believe is my basic attitude to much in life. It is also an analysis of particular relevance to the USA, a country I for many reasons feel close to. I have conveyed parts of my analysis to American colleagues in seminars and lectures inside and outside the USA, and I know they become unhappy. They are not necessarily disagreeing, on the contrary, but are unhappy at being seen as representatives – which they are – of a country with particular potentialities for developments like those I outline. It is of limited comfort in this situation to be assured that the chances are great that Europe may once again follow the example set by the big brother in the West.

But a warning is also an act of some optimism. A warning implies belief in possibilities for change.

The book is dedicated to Ivan Illich. His thoughts are behind so much of what is formulated here, and he also means much to me personally. Illich does not write on crime control as such, but he has seen the roots of what is now happening: the tools which create dependence, the knowledge captured by experts, the vulnerability of ordinary people when they are brought to believe that answers to their problems are in other peoples’ heads and hands. What takes place within the field of industrialized crime control is the extreme manifestation of developments Ivan Illich has continually warned against. I include references to some of his major works in the list of literature, even though they are not directly referred to in the text. They are in it, nonetheless.

Some final remarks on my intentions, and on language and form:

What here follows is an attempt to create a coherent understanding based on a wide range of phenomena most often treated separately. Several chapters might have been developed into separate books, but my interest has been to present them together and thereby open up the exploring of their interrelationships. I make an attempt to help the readers to find these interrelationships themselves, without too much enforced interpretation from me. The material I present might also be given quite different interpretations than those I have in mind. That would be fine. I do not want to create closure, enclosure, but to open up new perspectives in the endless search for meaning.

Then on language and form: Sociological jargon is usually filled with latinized concepts and complicated sentence structures. It is as if the use of ordinary words and sentences might decrease the trust in arguments and reasoning. I detest that tradition. So little of the sociology I am fond of needs technical terms and ornate sentences. I write with my “favourite aunts” in mind, fantasy figures of ordinary people, sufficiently fond of me to give the text a try, but not to the extent of using terms and sentences made complicated to look scientific.

2.1 All Alone

It is Sunday morning. The inner city of Oslo is as if deserted. The gates to the garden surrounding the University were locked when I arrived. So were the entrance door to the Institute and the door to my office. I am convinced I am the only living person in the whole complex. Nobody can see me. I am free from all sorts of control except the built-in ones.

Historically, this is a rather exceptional situation. Seen by nobody, except myself. It was not the life of my grandmothers, or of my mother, at least not completely. And the further back in the line I move, the more sure I am; they were never alone, they were always under surveillance. As a minimum: God was there. He may have been an understanding God, accepting some deviance, considering the total situation. Or He was a forgiving one. But He was always around.

So were also ordinary people.

Towards the end of the eleventh century, the Inquisition was at work in France. Some of the unbelievably detailed protocols from the interrogations are still preserved in the Vatican, and Ladurie (1978) has used them to reconstruct life in the mountain village Montaillou from 1294 to 1324. He describes the smell, the sounds and the transparency. Dwellings were not for privacy. They were not built for it, partly due to material limitations, but also because privacy was not that important a consideration. If the Almighty saw it all, why then struggle to keep the neighbours out? This merged with an ancient tradition. The very term “private” is rooted in the Latin privare – which is related to loss, being robbed – deprivation. I am deprived here on Sunday morning, completely alone behind the locked gates and doors of the University.

2.2 The Stranger

It was in Berlin in 1903 that Georg Simmel published his famous essay on “The Stranger – Exkurs über den Fremden”. To Simmel, the stranger was not the person who arrives today and walks off tomorrow. The stranger was the person who arrives today and stays on both tomorrow and maybe forever, but all the time with the potentiality to leave. Even if he does not go away, he has not quite abandoned freedom in the possibility of leaving. This he knows. So do his surroundings. He is a participant, a member, but less so than other people. The surroundings do not quite have a total grip on him.

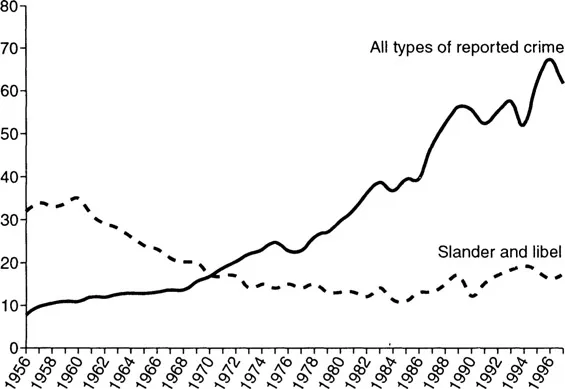

Georg Simmel would have enjoyed Diagram 2.2-1.

The unbroken line which hits the roof gives the number per 1,000 inhabitants of all cases of crime investigated by the police in Norway from 1956 to 1997. This is as usual in most industrialized societies. In absolute numbers it is an increase from 26,140 to 272,651 cases. The other line – here, since they are so few, measured per 100,000 inhabitants rather than per 1,000 as in the line for all crimes – shows cases of crimes against honour, libel and slander, acts which are still seen as crimes in my country. As we observe, the trend here is in the opposite direction. Crimes against people’s honour have gone down substantially during the last 35 years – in absolute figures from 1,103 to 745.

Diagram 2.2-1. All types of reported crimes investigated per 1,000 inhabitants, and slander and libel investigated per 100,000 inhabitants. Norway 1956–1997.

My interpretation is trivial. People are not more kind to each other or more careful in respecting other people’s honour. The general explanation is simply that there is not so much to lose. Honour is not so important any more that one goes to the police when it is offended. Modern societies have an abundance of arrangements – intended and not so intended – which have as their end result that other people do not matter to the extent they once did. Our destiny is to be alone – private – or surrounded by people we only know to a limited extent, if we know them at all. Or we are surrounded by people we know we can easily leave, or who will leave us with the situation of the stranger. In this situation, loss of honour does not become that important. No one will know us at our next station in life. But by that very token, our surroundings also lose some of their grip upon us, and the line for all registered crimes gets an extra upward push.

2.3 Where Crime does not Exist

One way of looking at crime is to perceive it as a sort of basic phenomenon. Certain acts are seen as inherently criminal. The extreme case is natural crime, acts so wrong that they virtually define themselves as crimes, or are at least regarded as crimes by all reasonable humans. If not seen so, these are not humans. This view is probably close to what most people intuitively feel, think, and say about serious crime. Moses came down with the rules, Kant used natural crimes as a basis for his legal thinking.

But systems where such views prevail also place certain limits on the trend towards criminalization.

The underlying mechanism is simple. Think of children. Our own children and those of others. Most children sometimes act in ways that according to the law might be called crimes. Some money may disappear from a purse. The son does not tell the truth, at least not the whole truth, as to where he spent the evening. He beats his brother. But still, we do not apply categories from penal law. We do not call the child a criminal and we do not call the acts, crimes.

Why?

It just does not feel right.

Why not?

Because we know too much. We know the context, the son was in desperate need of money, he was in love for the first time, his brother had teased him more than anybody could bear – his acts were meaningful, nothing was added by seeing them from the perspective of penal law. And the son himself; we know him so well from thousands of encounters. In that totality of knowledge a legal category is much too narrow. He took that money, but we remember all the times he generously shared his money or sweets or warmth. He hit his brother, but has more often comforted him; he lied, but is basically deeply trustworthy.

He is. But this is not necessarily true of the kid who just moved in across the street.

Acts are not, they become. So also with crime. Crime does not exist. Crime is created. First there are acts. Then follows a long process of giving meaning to these acts. Social distance is of particular importance. Distance increases the tendency to give certain acts the meaning of being crimes, and the persons the simplified meaning of being criminals. In other settings – family life is only one of several exam...